by Michael K. Townsley | Apr 29, 2022 | Strategic Planning

Earlier Predictions Come to Haunt Higher Education

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

A slow, plodding revenue growth strategy may no longer provide private colleges with the financial reserve needed to survive. For decades, marginal increases in enrollment, tuition, and other revenue sources were good enough to cover expenses and provide a cash buffer against unforeseen changes in financial markets. However, those days are quickly fading into the past. Moody’s Investor Services, Bloomberg News, and the Wall Street Journal claim that an increasing number of private colleges are in a death spiral due to shrinking enrollments coupled with the costs of providing traditional and on-line programs that prepare students for employment. The following graphs illustrate the characteristics of the problem facing private colleges.

Here are the major financial challenges:

- Total revenue varies widely by year because of investments

- If investments are removed, total revenue porpoises around expenses

- Administrative, academic-student services, and faculty costs either lag or are directly affected by changes in enrollment

- Net assets have varied widely due to major swings in revenue

- Net asset forecasts are not promising and remain unsettled

There are also non-financial challenges:

- Governmental regulations

- Tuition rates

- Gainful employment

- Accreditation constraints

- Tenure

- Curriculum structures

- Technological changes in delivering instruction

- Changes in degree payback, which alters preference for degrees

The challenges are producing these pressures:

- Pricing pressure from:

- Demand, fewer high school graduates

- Costs to support declining academic skills

- Cost of technology

- Cost of regulations, government and accreditation

- Unpredictable returns from investments

- Operations do not produce sufficient cash to provide reserves in times of financial stress

- Recent (4/14/14) Bloomberg article: “Small U.S. Colleges Battle Death Spiral as Enrollment Drops” (Michael McDonald)

How private colleges are being reshaped:

- Too many private colleges are operating at the margin putting them at risk as student markets change and new and costly technologies are introduced.

- Private colleges cannot continue to increase their tuition discount without depleting the cash flow from tuition to support operations.

- Public institutions need a comprehensive tuition discounting strategy as their price competition increases and competition increases with on-line programs at private colleges.

- Experience suggests that operations at many private colleges absorb cash and do not generate cash.

- Cost structures are too expensive.

- Market strategies need to account for government regulations that:

- Limit price increases; thereby increasing competition.

- Require publication of the economic viability of graduates

- Existing markets (revenue sources) are not large enough to offset forecast shrinkage of the traditional market for high school graduates.

- Data systems are inadequate to support operations and to improve student performance.

- Investment policies are too volatile for many private colleges.

- Public colleges have to evaluate their reliance on state funds as states continue to reduce funding formulas.

As colleges are being reshaped, they are facing these existential issues:

- Are financial reserves being depleted at traditional bachelor’s degree granting colleges?

- Will private colleges and universities have the financial reserves to compete?

- Do private institutions have the administrative and technical skills to build a strong technological base?

- Can colleges find student markets that do not require huge investments in technology?

- Are private colleges willing to develop new ways of reducing costs, delivering instruction, and working with competitors?

Here are the probable outcomes from the challenges, pressures, and existential issues facing private colleges:

- Colleges will look the same as they do now with minor changes to account for new regulations imposed by federal and state governments.

(Estimated probability is 10%)

- Most liberal arts colleges will be forced to redesign their programs to respond to parent and student demands that their degree prepares them for employment.

(Estimated probability 30%)

- Many liberal arts colleges will shift their resources toward internet delivery for day and continuing education students in order to cut costs generated by new regulations (such as new costs to increase graduation rates) and to respond to limits on tuition rates imposed by governmental regulations.

(Estimated probability 15%)

- Vendors will provide very cheap standardized virtual reality courses that colleges will buy replacing self-developed courses and full-time faculty.

(Estimated probability 20%)

- More colleges will face cash crises forcing them to: permanently cut expenses, merge, or close.

(Estimated probability 15%)

- Multiple colleges will create implied or pseudo mergers in which they build a separate institution owned by the participating colleges that contains several or all of the preceding five scenarios.

(Estimated probability 10%)

by Michael K. Townsley | Apr 29, 2022 | Enrollment and Marketing

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

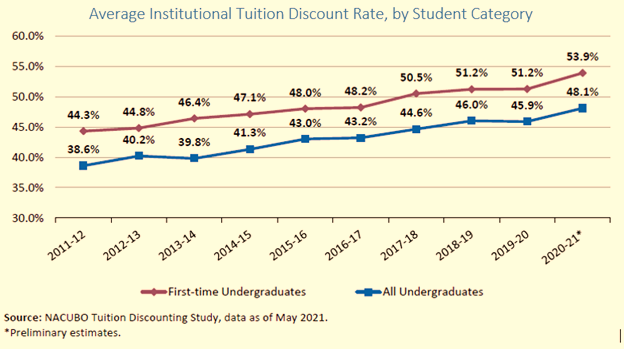

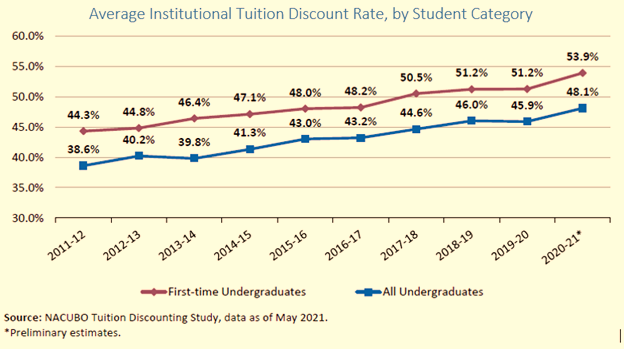

Typically, when market demand shrinks or supply greatly exceeds demand for a product or service, fierce price competition comes into play among competitors. The ongoing decline in student demand for enrollment is already showing considerable evidence that price competition (net tuition) is escalating. As is evident from the following chart published by the National Association of Colleges and University Business Officials, between 2011-12 and 2020-11 tuition discounts for first-time undergraduates increased 9.6%. Increases in tuition discounts reduced the cash flowing from tuition which reduced the cash available to pay for operational expenses. Another way of seeing the effect of larger tuition discounts by 2020-21 is that for every $10,000 of tuition revenue from new students cash flow from tuition will reduce by $960. If a college enrolls 100 new students, the total loss in cash flow in 20-21 would be $96,000, which equates to the capacity to support two instructional positions.

Based upon the preceding table, it is not unreasonable to assume that, in response to the basic supply- demand relationship, prices are falling in reaction to increased competition for a shrinking pool of potential students. The following table shows that since 2000 the number of births bounced up and down with dramatic declines after 2006 and 2014. Forecasts by the Department of Education and others suggest that declining births will continue forward throughout the 2020s.

Many private colleges, when designing marketing campaigns, must account for prospective students who believe that there are only small differences in majors among prospective institutions. So, how does a college respond to shrinking markets and student perception that differences between colleges are meaningless? If given the preceding conditions lead to colleges becoming more aggressive in discounting tuition, colleges must sharpen how they present price discounts to prospective students. Below are several themes that private colleges might consider:

Quality Education at a Reasonable Price

Reduce Out-of-Pocket Costs with College XYZ New Financial Aid Packages

Cut Your Tuition Debt with College XYZ’s New Tuition Charges

XYZ College Offer an Affordable Degree with Our New Tuition Aid Packages

Contact XYZ College about Our New Lower Tuition Rates

Don’t Pay More for A Quality Degree, Contact XYZ College, Now

by Michael K. Townsley | Apr 29, 2022 | Presidential Leadership

DOE Doesn’t Get It! Others Are Working on It. Here Is What Is Useful!

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

The Voluntary Institutional Metrics Project has worked for two years designing a common dashboard for institutions of higher education. The purpose of the dashboard is to display the cost of a degree, the default rates for graduates, and the skills attained by graduates. The major problem with the project is that very few institutions have the data or the analytic tools to get at these measures. Very few colleges have the operational or financial data to determine what all degrees cost, what skills have been mastered, or the cost or skills for a particular degree.

Setting goals is simple yet having the capacity to achieve those goals is not. A goal such as determining the cost of a degree appears on the surface to be a straight forward and achievable outcome, but it is easily overwhelmed by massive data issues. Here is the essence of the problem in costing a degree – colleges would have to track the cost of every student that is graduating by degree. In most cases, administrative and financial systems do not differentiate associates, bachelors, masters, or doctorate degrees. Redesigning a college data system to figure out the cost of a degree would cost a small fortune and would take an immense amount of time, neither of which colleges, especially small colleges that are struggling, have in abundance. Several presidents who participated in the Metrics Project complained about the disconnection between project goals and the cost to generate the metrics to achieve those goals.

Dashboards are necessary and useful tools for presidents and boards of trustees. At this time, the Project Dashboard may be too ambitious. What key decision-makers need from a dashboard is a quick picture of the current data and forecast conditions of the college within its operating year. The dashboard should also point out problems with an attachment to explain how the problem will be resolved. Listed below are several common elements from the literature and from the experience of Stevens Strategy that should be part of a dashboard:

Simple Financial Dashboard – the report should not be overly detailed, but it should include the main sources of revenue, expenses, and several additional measures to show the capacity of the college to pay for current operations and obligations. The highlighted items can also be displayed as charts.

Operational Dashboard – this report lays out several factors that drive financial performance for the current fiscal year and for the next several fiscal years.

These two dashboards recognize the data limitations at most colleges, which constrain what they can report. It is in the interest of colleges and their attendant business offices to do the following to improve their ability to analyze performance and to respond to new federal requirements.

- Chart-of-Accounts – design the chart so that it can include every revenue producing program and its attendant expense departments that accurately reflect the operational structure of the institution. In addition, expenses should be sub-divided so that their impact on revenue production and on supporting operations can be identified and analyzed.

- Assets and Liabilities – the chart should be designed so that it also reflects the revenue flow and expense departments in the operational structure of the institution.

- Payroll – this system should also complement the chart-of-accounts.

- Depreciation and Interest – should be allocated and updated to assign space and interest to the correct revenue and expense departments.

- Enrollment System – the coding for enrollment by student and by credit hour and the coding in the chart-of-accounts should complement each other so that enrollments and financial accounts for each academic program can be aggregated and analyzed.

- Reports and Analysis – the institution should design reports so that it can carefully analyze its operations and the effects of its operational decisions. Annually, the key decision makers should meet to intensively review the effectiveness of its strategy, its operational decisions supporting the strategy, and the performance of its instructional delivery system, marketing plans, capital investments, and financial structure. Furthermore, on-going, revised, and new strategies should be tested through its financial forecasting model.

Even though most institutions are not ready for the intensive data requirements under the expected Department of Education reporting regulations, colleges and universities should prepare their financial and operating systems now. Good data not only will provide the basis for compliance with expected federal regulations, but good data also gives the institution the information needed to analyze their costs, productivity, and strategies.

by Michael K. Townsley | Apr 27, 2022 | Financial Strategy and Operations

In 1986, more than 900 independent colleges derived at least 75 percent of their revenue from students, according to a 1989 study by Minter and Associates. This figure has probably changed little in the past eight years. Too often, enrollment-dependent independent colleges find that actual enrollments are dramatically different from budget projections. Because financial reserves at these institutions are so meager that small discrepancies between forecasts and fiscal performance can be disastrous, financial officers must find a way to monitor budget status.

The longer it takes to discover that tuition targets do not match the budget forecast, the more difficult it is to solve the problems. Options disappear during the academic year as discretionary expenditures are allocated. Conversely, the pleasant possibility of extra funds can be dashed if planners have made false assumptions about the size of the anticipated surplus. Plans for expected excess tuition revenue must take into account associated costs such as faculty salaries and instructional supplies.

Clearly, an ongoing system of short-term budget controls that test actual performance against budget forecasts is essential for enrollment-dependent independent colleges. By definition, these institutions often lack the resources to supplement enrollment revenue with endowment or other funds.

CASE STUDY: WILMINGTON COLLEGE

The experience of Wilmington College, a small, fast-growing independent college in Delaware, demonstrates the difference a well-tailored budget control model can make. The college, which has developed and applied its budget control system over the past eight

years, offers degrees at the bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral levels. More than 70 percent of Wilmington’s students attend part-time; their average age is 27. Enrollment has grown at a compound rate of 12 percent over the past five years, reaching nearly 3,900 in 1994. The enrollment dependency rate (tuition and fees plus bookstore sales, divided by total revenue) was 93 percent in 1994.

Instructional programs are conducted at five sites throughout the state, each of which sets a tuition rate based on its fixed costs. Therefore, the college publishes five rates of tuition for each program. A corps of veteran adjunct faculty members (most of whom work at one of the state’s Fortune 500 corporations) teaches 82 percent of the courses.

The combination of a multiple price structure and a large number of adjunct faculty results in a complex budget. Financial controls are imperative. Prior to the introduction of the budget performance tracking model in the mid-1980s, annual deficits were commonplace. Deficits generally occurred because of an unanticipated decline in enrollments or because direct expenses out-paced enrollments. Even when enrollments exceeded the budget forecast, the college often could not avoid a deficit. The extra revenue only fueled the demand to spend, which is not unusual for an institution that depends on surplus revenues to fund capital improvements and equipment. The extent of the deficit was never discovered until the end of the fiscal year, when it was too late to take any deficit-reduction actions.

The problem Wilmington College faced was how to stop this chain of unforeseen

Michael K. Townsley is senior vice president at Wilmington College.

deficits. The fall semester of 1985 found the college with a smaller student body than expected and a governing board that had become exasperated with the college’s inability to control its finances once an enrollment trend developed. The finance office was obliged to devise a system for closely monitoring its tuition revenue; the rudiments of the control model began to take shape that year.

During the fall, the finance office started to track tuition revenue closely as it was posted. Financial officers soon found that regular budget reports covering only tuition were inadequate, and decided that figures on adjunct faculty expenses also needed to be included. In other words, the original presumption had been that if enrollment fell, the number of classes offered would decline proportionately. But that proved to be false. The number of classes is driven by instructional program demands, as well as enrollment. Even with small class enrollments, certain courses must be offered periodically for students to be able to complete their program requirements.

In the spring, the costs of adjunct faculty expenses were added to the tracking program. Any possible deficit could be estimated by comparing tuition revenue and the cost of additional adjunct sections to the original budget. For the first time, this gave the college sufficient forewarning to initiate a cost-cutting program to eliminate a deficit.

During the summer of 1986, this simple monitoring system was reviewed to determine how it could be revised to improve efficiency. Four flaws were immediately apparent:

• Tuition and direct expenses were not accrued.

• Gross income (tuition minus adjunct faculty) was not computed.

• Payroll tax variances were not estimated.

• The budget was not subdivided according to the academic schedule.

As these defects were remedied, the existing control model took final shape. The first change was to begin accruing tuition revenues and adjunct payroll by academic period. (Over the years, accrual accounting has been expanded to the bookstore and to all revenues and expenditures that had a sign ificant potential for varying with the budget.)

Next, the college began computing gross income, which is important because it is the predominant source for the funds that cover fixed costs. The only refinement to this computation has been to add the gross income from each site to give a total gross income.

Another line was added after the gross income, estimating social security taxes based on any variance in the adjunct payroll. This too was summed to give a total payroll tax variance for all sites. Finally, the budget was divided into academic periods so that it could be compared to the accrued balances in the ledger. (An initial breakout by month provided more detail than proved necessary.) The last major revision to the control model, carried out in 1990, translated it into a Lotus program, which quickly compiles the data and produces a summary report.

The budget control model concentrates only on those variable revenues or expenses where unexpected differences from the budget may have a major impact on the status of the current unrestricted fund. The reporting procedures used are based on commonly accepted practices for variance reporting. This model accounts for all expenses that vary, whether related to instructional, administrative or support services.

The model uses five equations, each of which depicts a benchmark in the flow of tuition revenue through direct expenses to net income. (See Exhibit 1.) The equations are computed in sequence at the end of each drop/add period on a year-to-date basis. Each equations’ output is compared to a budget benchmark to ascertain variances.

The equations depend upon a budget that forecasts the variables and benchmarks for each academic period during the budget year. The ledger system also must provide data that clearly depict the financial transactions for the academic period.

Benchmark equation 1 identifies the amount remaining after the adjunct and full-time faculty overload costs are deducted from tuition. The initial step in computing this equation is to translate enrollment figures into tuition revenue, based on data from the registrar’s office. Enrollment is subdivided by site and by any deviation from the posted tuition not due to a scholarship award. Tuition revenue is then calculated by simply multiplying the appropriate tuition rate times the enrollment.

The second step in computing the equation is to add the adjunct faculty overload contracts for each site. (The contract should describe the amount paid and any adjustments made, such as a prorated payment based on class size.) The resulting figure,

$B 1, is the contribution margin—the expenses, as defined by R.N. Anthony and difference between variable revenues and

D.W. Young in their book Management Control in Nonpro fit Organizations. The final step is to compare the resulting figure to the budget forecast to see if a variance exists.

Benchmark equation 2 deducts direct expenses related to tuition or to instructional expenses. Adjustments to tuition revenue include payment defaults, withdrawal refunds, and scholarships in excess of the budget. Adjustments to instructional expenses are instructional support and social security taxes. A payment default is included only if it exceeds the amount set aside in the budget for a student’s outstanding bill. Similarly, scholarships are recognized only when they surpass the budgeted limit. A withdrawal refund denotes a refund made after the drop! add period ends. Prior to that, any adjustment to tuition revenue due to withdrawals should have been divulged through the enrollment report.

Instructional support is usually revised only when enrollments exceed the forecasts, as extra funds may well be needed for instructor materials, classroom space, computer software, and equipment. Excess social security taxes are computed by multiplying the variance for adjunct and full-time faculty overloads by the rate for social security taxes. (Some institutions may have to consider other payroll items such as unemployment taxes, workers’ compensation, or institutional benefits.)

Benchmark equation 3 takes into account any variances in nontuition revenues, such as money from student fees or from the net income projected for the bookstore. (These items are not intended to be exhaustive. Other institutions may have other revisions to revenue that are related to enrollments, such as dining hail or housing income. For some colleges, nontuition revenue plays a significant role in the financial structure of the institution. If this revenue or its attendant direct expenses vary substantially from the budget, the variance needs to be reorganized in benchmark equation 4.)

Unanticipated changes to the expense budget for other instructional expenditures are recognized in benchmark equation 4. The original budget often needs to be fine-tuned because it was based on incomplete information. For instance, medical insurance rates may be higher that originally estimated, or the rate of inflation may have risen faster than expected, causing utility expenditures to skyrocket. Furthermore, unexpected emergencies, such as equipment breakdowns, accidents, or bad weather, may have befallen the campus. As a result, other budget items must be modified other than those directly related to tuition revenue.

Variances from the first three equations are summed in benchmark equation 4. The total variance resulting from this equation, $B4, equals the estimated net income projected for the budget year. A positive net income signifies that benchmark 5 is to be computed. However, if $B4 reveals a possible deficit, the college devises an expenditure reduction plan. (The nature of the spending cuts will depend on the institutional climate and governance structure.)

Benchmark equation 4 indicates only the direction and the potential scale of the net income at that period in the budget year. It does not signify what will subsequently happen. Data from the control model need to be extrapolated to forecast the balance of the budget year.

The purpose of benchmark equation 5 is the allocation of any excess revenues identified. Of course, any surplus indicated by $B4 may have to cover revenue shortfalls or unexpected expenditures later in the budget year. Thus, it would be prudent to set aside a portion of the surplus until the end of the drop/add period for the last academic period of the budget year. The allocation of the surplus from benchmark equation 4, like the deficit reduction plan, should come from plans made by the appropriate decision mak

ers in the governing structure. In most instances, those plans should be approved by the president.

The results of the benchmark equations can be assembled in a report, to be sent to the president and other key officials. Those receiving the report will depend on the polity of the institution. The reports should be prepared and distributed at the conclusion of each drop/add period in the academic schedule. These reports provide data on the financial status at a critical point in the flow of new tuition revenue, when the decisions on direct expenses are still fresh in mind.

SAMPLE CALCULATIONS

The results from each of the benchmark equations can be assembled in a standard budget report, as shown in Exhibit 2. The sections correspond to the five benchmark equations; the rows conform to the variables in the benchmark equation; and the columns show amounts for the budget, performance, and variances, using year-to-date figures. At the end of each benchmark section, rows and columns are summed. Each section after the first carries forward variances from the previous section. A grand variance is given at the end of the report.

ACCOUNTABILITY CRUCIAL TO SUCCESS

The success of this model depends on number crunching as well as combining the model with an administrative mechanism that builds in accountability by defining the performance levels expected for each benchmark, and by ensuring that an administrator is responsible for the performance at each level of the benchmark. Identifying a responsible administrator means that the institution can turn to someone for a report on what is happening with each benchmark variable. This manager can also suggest a course of action when problems arise.

The budget should define the performance levels expected for each benchmark. Centers should be set up to monitor, control, and manage the major revenue and direct expenditure streams for an institution. Reports should be directed to center administrators or to decision makers in the governance structure so that plans can be developed in response to positive or negative variances.

Financial controls should focus on those components of the budget transactions where variances may occur and may have a substantial impact on the financial condition of the institution. Specifically, the model should track variable revenues, variable expenses, the contribution margin, and the mix of services. This model concentrates on van

able revenues, represented by tuition revenue. It works with variable expenses in terms of adjunct contracts, instructional supplies, payment defaults, withdrawals, scholarships, taxes, student fees, and bookstore net income. The contribution margin is controlled by taking the difference between tuition revenue and variable expenses. Finally, the model employs centers as the mechanism to oversee the mix of services.

THE BOTTOM LINE: NO DEFICIT IN EIGHT YEARS

The biggest challenge to Wilmington College since the 1985-86 budget year has been to keep pace with the college’s rapid growth. In 1992 alone, enrollment grew by more than 21 percent, mainly due to the addition of three new instructional programs. Decisions during such growth spurts have to be made quickly: classrooms must be constructed and staff hired. The control model has proved a boon by giving the administration a quick, precise picture of its net income. In most of these years of rapid growth, the surplus income was allocated toward capital expenditures and the hiring of new staff well before the end of the fiscal year. Nevertheless, the college has not had a deficit in more than eight years, despite these demands on its surplus revenue.

This happy state of affairs has resulted partly because financial risk is lessened by having better financial data disseminated quickly to those who need to know. The model helps to militate against the concentration of power in the business office because it depicts the dynamics determining the bottom line. As indicated, the reports produced by the application model are given the widest dissemination within the governance structure.

Finally, as Philip J. Bossert, in his manual for NACUBO, Management Reporting and Accounting for Colleges and Universities, and L.H. Gitman, M.D.Joehnk, and G.E. Pinches, writing on financial management in Managerial Finance, note, variance analysis should be used as a reference for improving the budget and the control model. The model lends itself to this usage in two ways. First, it keeps in the forefront the dynamic conditions that drive an enrollment-dependent college. In particular, it is a tool to continuously inform management of any changes that are taking place in the all-important tuition revenue stream. Furthermore, working with the model suggests further refinements that will improve its precision. The current model is not the final form; revisions will continue to manifest themselves as the model is put to further use. —