by Michael K. Townsley | Sep 29, 2024 | Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis

What is a Financial Crisis

Essentially, all financial crises are cash based. Simply put, if there is no cash, there is no college. In most cases, the crisis is cumulative, and the cause or causes have depleted cash over several years until a point is reached where there is insufficient cash for on-going operational and capital expenses. The crunch becomes evident when the chief financial officer informs the president that there is insufficient cash to make payroll, pay vendor bills, or cover debt-service expenses. The cash problem is usually magnified when the college banks no longer extend short-term loans for operating cash. When a college has depleted its cash reserves and cannot get short-term loans, its board of trustees faces an immediate financial crisis. Under these circumstances, the board has to ask two questions:

- Does the current leadership have the wherewithal to get the college out-of-the crisis

- Are there any board members who have the means to guarantee a short-term loan or to make a donation that will carry the college for at least six months.

After you have answered those questions, these should be the immediate next steps:

Understand the Cause

- Understanding the cause of the crisis requires a good chief financial officer, a cooperative auditor, and a president who can quickly fathom the cause(s) of the crisis.

- Find out why cash is being depleted; is it due to

- Falling enrollment

- Shrinking net tuition revenue

- Deficits in auxiliary services

- Too many loans and too much debt service

- Expenses-out-of-control

- Is the average class size too small?

- Are there too many majors?

- Are attrition rates growing faster than enrollment?

- Is the ratio of students to employees too low?

- Are there too many faculty?

- Are there too many administrators?

- Is the cost of academic and student support services growing faster than net tuition revenue?

Essential Factors Needed for Success:

- President who has a strong turnaround leadership team

- If not, find a turnaround expert – either to replace the current President or hire them as a Chief Administrator

- An attorney who knows all facets of education law

- Board of Trustees who willingly invest time, energy, and funds in the turnaround

- Recognition that time is short, and action must happen quickly

Immediate Action – Find Cash:

- The board needs to meet frequently to approve action and grant authority to the president to take immediate steps to save the college.

- Hire a good attorney versed in higher education law.

- When returning students arrive for Fall/Spring classes are balances paid?

- Do all students have a method for paying for upcoming semesters?

- Stop all purchases except for emergencies.

- Do not hire new employees to fill empty positions.

- Release employees who are not critical to the operation of the college.

- Meet with all third-party contractors to either end the contracts or cut the costs.

- Meet with all banks to reduce or delay debt service payments.

- Prepare a large endowment loan; this usually requires approval by the state.

- Use the endowment loan to pay-off or pay-down loans from financial institutions.

- Consolidate offices, classrooms, and other space into a central core on the campus.

- Eliminate academic programs in which direct expenses exceed revenue.

- Arrange to lease or sell any low-use or empty buildings.

- Sell any external property that is not contributing positive cash flows.

Strategic Action

- The data and information collected in the “Understanding the Cause” stage should be the basis for strategic action.

- Strategy should be designed to eliminate deep structural problems that led to the financial crisis.

- Strategy should focus on new programs that have strong payoffs for graduates.

Mistakes to Avoid as the Crisis Unfolds

- Assuming that the crisis is solely a short-term cash problem and ignore the underlying structural failures that lead to the crisis.

- Bringing in a turn-around president without giving them the authority to work on the underlying structural problems.

- Replacing the turn-around president as soon as the cash crisis is resolved and hiring a president who returns the college to an operational state that causes the structural problems to resurface.

by Michael K. Townsley | Sep 29, 2024 | Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis

Overview:

Private college leaders, especially presidents of small colleges, are tasked with maintaining the financial viability of their institution and avoiding strategic and management errors that threaten the continued financial viability of their institution. Shrewd presidents must recognize that tried and true strategies, policies, and programs that successfully generated reliable financial stability many now undermine the financial stability of their institution.

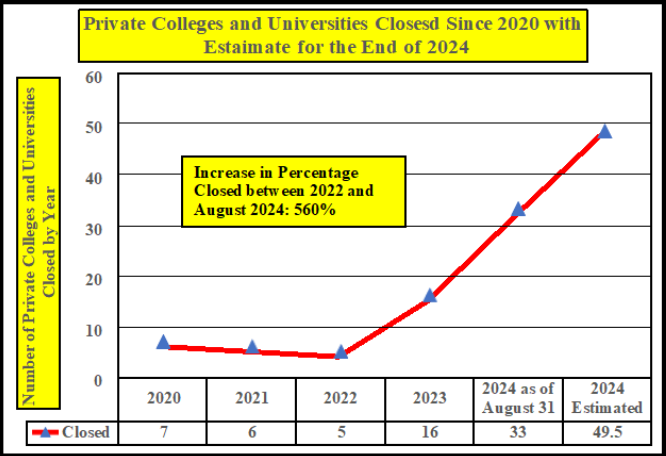

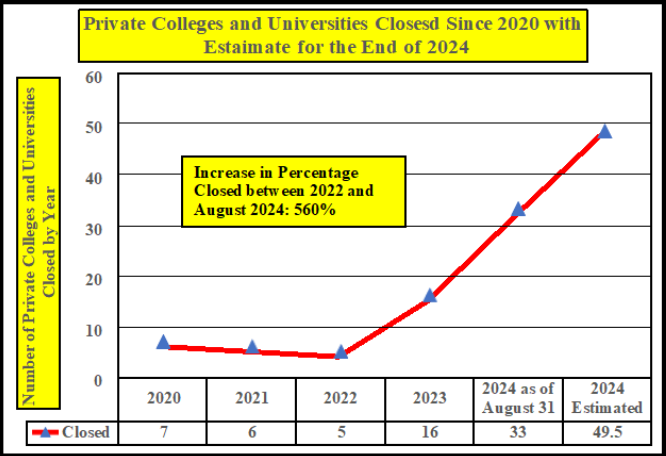

It is readily evident that private not-for-profit institutions are in severe straits with colleges as the pace of closings and mergers have increased between 2022 and 2024.

The purpose of this paper is to identify and comment on strategic and management decision that can place a private college at a high, risk of closing.

Strategies that Undermine Financial Viability

Until the student market collapsed since the turn of the century, there were a set of strategies that worked well to grow colleges. However, some of these strategies no longer work as expected due to shrinking student markets, changes in prospective student preferences for post-high school education, inflation, and fierce price competition as colleges struggle to enroll students. Below, is list of high-risk strategies with brief comments about their threat to financial viability.

Strategic Risk #1: Field of Dreams – Build Dorms and they shall come. Very expensive, high-risk decision is out of tune in a time of enrollment decline. Colleges that were late ‘to the field of dreams’ often find that their competition has fully exploited the potential of this strategy. Coming in late on massive dorm building in expectation of enrollment can lead to empty dorms and excessively high debt loads

Strategic Risk #2: Overcollateralization – this risk follows from Strategic Risk #1.

Overcollateralization happens when a financial agency believes that the college debt loads are excessively high and demand protection for their load by requiring the college to collateralize most or all college property. As a result, the college loses the flexibility in times of cash crisis to sell property. They will need the lender’s approval to sell, and they may not approve the sale because it increases the risk of the loan. Also, government regulations may limit the total risks held by the lender, and if the loans to the college are a large part of the lender’s loan portfolio, they could be at risk of governmental regulatory action.

Strategic Risk #3: Third-party contracts for enrollment – often this strategy follows from Strategic Risks #1 and #2. It is not uncommon that private colleges contract with third parties to recruit students. The catch is how payment for services is determined. The first issue is how is an enrolled student determined under the contract. Is a student counted if they remain a student through drop-add or through the end of the semester or fiscal year. In this instance, payment after drop-add is a very low bar given the volatility of students today. The second issue is the amount of payment per student for the third party. Is payment premised on a charge per tuition or tuition and fees. Obviously, the second method is much more expensive to the college. Lastly, what is the cost of the services? Since most third-party enrollment agencies charge a percentage, the scale of the percentage can have a significant effect on the amount of money that the college retains from student tuition. In some cases, according to information available to the author, some colleges are paying 25% of tuition and fees for new student enrollment. Strategic Risk #4 speaks to the threat to the college’s financial condition after the percentage owed on the agency is paid.

Strategic Risk #4: Tuition discounts that substantially exceed the national average – this risk often follows from Strategic Risks #1 through 3. According to the National Association of College and University Business Officials (NACUBO), The national average on ‘unfunded tuition discounts’ for 2023-24 was 56.1%.1 Assuming the average rate for 2023-24, the college would receive about forty-four cents in cash. Obviously, that is putting more pressure on the college to control expenses. If a college is paying a third- party twenty-five cents on a dollar of tuition and fee revenue, then they are getting only nineteen cents back in cash, which is a very paltry amount needed to cover direct expenses. Anecdotal evidence indicates that some colleges are offering ‘unfunded tuition discounts’ greater than 70%. For these latter colleges, they are only receiving thirty cents on a dollar of tuition. Colleges that offer 70% discounts and are paying 25% fees per new student are only receiving five cents on the dollar. No tuition-driven, private college can survive on this paltry return on a tuition dollar.

Special Comment on Strategic Risks for #1 through #4 – Cascading Effect:

Financial threats cascade for private colleges that came late to the ‘Field of Dreams’ strategy, are loaded with debt, are over-collateralized, use a third- party enrollment service, and pay a high fee for new students. It would be surprising that colleges facing this strategic risk cascade could survive very long. Survival for these colleges will depend on the scale of cash reserves and the ability of its president to convince the state attorney general to borrow large sums from its restricted endowment. A prudent attorney general as final arbiter of the college’s funds, might find it inappropriate to grant such a request.

Strategic Risk #5: Build Revenue by Adding Dozens of New Academic Programs. This is an old chestnut that was contained a wisp of wisdom when the student market was sufficiently fluid that students would come even if the new program was a very small niche in the market. However, too often, colleges now find that they have hired too many faculty, may have even tenured those faculty, yet only a handful of students are enrolled. In today’s financial environment, this strategy is a loser that probably does not come close to covering direct costs, let alone indirect costs.

Strategic Risk #6: Independent Entities. The board establishes independent entities that offer credit and degrees that are outside faculty oversight, the academic governance and presidential control. These entities may violate accrediting commission rules, which might find that because these entities lie outside the academic governance structure that the credits or degrees are not legitimate. Such finding by an accrediting commission could also have an adverse impact on Title IV financial aid funding by the US Department of Education.

Strategic Risk #7: Trade Enrollment for Academic Standards. This problem dates back to the late sixties when colleges and faculty began to dilute the curriculum to accommodate the interests of students in response to student protests. David Reisman and Christopher Jencks were the first to address this issue in their book The Academic Revolution2

Strategic Risk #8: Failing to Perform Due Diligence. Too often college boards and president do not carefully read a costly and/or long-term contract nor thoroughly analyze the financial impact on the finances of the institution. The preceding example about enrollment recruitment agencies is a good example. Heavy financial burdens can also arise from bond covenants or loan conditions, or even faculty and staff contracts. The failure of due diligence can deplete financial reserves and constrain the strategic and operational options in response to a crisis.

Cautionary Note – Leadership:

A private college facing an impending financial crisis needs a president that: is assertive, focuses on action to stem the crisis, works with the faculty with the understanding that they are in an advisory role and not a decision role, and works closely with board to press forward with change. During a financial crisis, some presidents remain passive agents of change that are dependent upon the vagaries of issues thrown their way by a self-interested and opportunistic academic governance system. These presidents will fail to gain the momentum needed to arrest the impending financial crisis.

Policies and Practices Risks (P & P) that Undermine Financial Viability

Although misbegotten strategies have the potential of dealing a fatal blow to the financial viability of a college, ill-conceived policies and procedures can also foster a financial crisis and confound actions to stem the crisis. This section will describe several of the more prominent policies and practices that need to be resolved during a financial crisis.

P & P #1: Excessive rates of tenure and long-term contracts imposes long-term costs that are difficult to reduce, and they reduce the flexibility of the board and president to change the mission and structure of the academic programs.

P & P #2: Course schedules that do not allow students to complete their degree within a four-year cycle. This leads to an excessive number of independent studies as faculty arrange courses so that students can complete course requirements. This is a very inefficient practice because it reduces class size to 1 and adds the costs of the independent study to operations.

P & P #3: Released time to staff and faculty increases costs without generating significant benefit to the institution and to its student

P & P #4: Failure to Pay for the best experienced key people

P & P #5: Adding new faculty, staff, or administrators, when existing employees do not carry out their duties, because it is easier to add personnel than to fire underperforming employees.

P & P #6: Hiring new persons whenever staff or faculty or administrators that the workload has increased without evaluating the assertion. Too often the additions, do not necessarily improve the delivery of services but diminish service output to the detriment of students

P & P #7: Excessive effort is spent on generating and acquiring grants that distort the mission and operations of the college and do not sufficiently contribute t its financial stability.

P & P #8: Providing assistants to do menial servant work for faculty and administrators, ex. copy papers, pickup mail, get supplies, and type papers in an era of personal computers.

P & P #9: Failing to use legal counsel to review board policies, contracts, major human resource issues, governmental relationships, and other matters that could result in legal action.

P & P #10: Not following policies, procedures, and contractual handbooks when introducing change or responding to problems.

P & P #10: Not regularly reviewing board by-laws, college policies and practices, faculty and student handbooks, and other documents that govern decisions.

P & P #11: Irregularly revieing financial reports of the college and by department and not receiving estimated end-of-the-year budget reports during the year.

P & P #12: Perfunctorily signing purchase orders and staff reimbursement reports without determining if the purchase fits the goals and mission of the college and the reimbursements are justified given the policy of the college.

Summary

The preceding list of Strategic and Policies and Practices Risks is not a comprehensive compilation of the risks to a college in financial crisis. The lists are meant to inform presidents and boards so that they can improve their chance of successfully responding to financial crisis.

The keys to a successful response to an impending financial crisis are:

- Timely recognition of an impending financial crisis by the Board of Trustees and President

- Understanding the causes of the crisis

- Presidents who recognize the crisis and can expeditiously formulate responses and bring the community to action

- Support of the President by the Board of Trustees

- Taking action and not dithering in discussion.

- Using a financial crisis team, in which the best persons in their respective field are hired. The team would include:

- Chief Academic Officer (CAO) – in addition to the faculty, must know how all the department to this officer operate and should be able to step in and do the work.

- A president, who has worked with the faculty and even worked with departments reporting to the CAO should be able to run this position. This would only occur if the CAO position is empty or lacks the skills or refrains from making the necessary and difficult decisions during a crisis.

- Chief Enrollment Officer (CEO) – this person should show experience in designing an effective recruiting students and marketing the college. The CEO should know how to use all forms of communications to reach the student market and track them through enrollment and the first year of study.

- Chief Financial Officer – this position should be filled by a certified public accountant (CPA) who has directly supervised business and financial operations. The CFO should also have experience managing current debt and refinancing debt packages, managing operational and capital contracts, and preparing regular budget and financial reports for the president, the Board and the crisis team.

- Chief Human Resources Officer – this position is critical because of the likelihood that the transformation will result in large number of dismissals, revision of pay schedules, or redesign of work policies and procedures. This person should proficient in governmental employee laws and regulations in addition to the employee policies and procedures of the college

References

1 Scwartz, Natalie (May 22, 2024); “Tuition discounts at private nonprofit colleges hit new high, study finds”; Higher Ed Dive; Tuition discounts at private nonprofit colleges reach new highs, study finds | Higher Ed Dive.

2 Reisman, David and Christopher Jencks (1968); The Academic Revolution; Doubleday; New York.

by Michael K. Townsley | Sep 29, 2024 | Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis

Presidents and boards of trustees often respond to a financial crisis with a destructive contest in which a board resists the presidents for greater authority. President’s takes the lead because they believe that an effective response cannot take place unless they have more authority to make changes through all levels of the college. The board pulls back from the president’s request because they fear that the college will lose its historic identify and not be able to deliver on its mission.

Here are examples of the push-pull over authority between presidents and boards of trustees.

- The most obtuse case in the push-pull of authority is where the board does not include in its by-laws that it retains final authority over all decisions.

- A particularly annoying case for presidents is when a board prior to the crisis relinquishes its authority over academic programs and decisions on hiring, reassigning and dismissing members of the faculty.

- For president’s the most troubling authority transfer to the faculty is when the board permits the faculty to determine the conditions for tenure, the number of tenure positions, and the procedures for reviewing tenure.

- Another short-sighted decision by a board is when they expand board membership to include members of the faculty. The ostensible reason given by in some instances is to improve communications between the board and the faculty. Granting membership to the faculty for this reason is a clear statement that they do not trust the president. Here are several other problems with placing faculty on the board:

- Faculty are self-interested members at a time, when the board needs to be disinterested in the outcomes of its decisions.

- The faculty become privy to personnel action that may affect a member of a colleague.

- The faculty members could carry back to colleagues; sensitive information about strategic options and personnel changes. Under this circumstance, a cautious board could forfeit open discussion.

- Even more debilitating is when a general uproar in the college results in leaks to the press. The danger with leaks to the press is that governmental agencies and accrediting bodies may become involved prematurely in options that are only under consideration.

- Disagreement between the board and president over the degree of authority to grant the president during a financial crisis may not be resolvable. Nevertheless, the board’s decision on granting additional authority can be critical, if the president has a credible strategy to end the financial crisis. Not granting the necessary authority can doom the possibility of stemming a financial crisis. In a deep financial crisis, time is of the essence.

In summary, the problem with authority boils down to the makeup of the board. For an interim president, the board is inherited and nothing can be done to change its makeup. In these cases, a president faces a conundrum similar to what a former Secretary of Defense said about armies and war. In war, in particular, a short-war, you use the army that you have not the army that you wished you had.

by Michael K. Townsley | Sep 19, 2024 | Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis, Strategic Planning

Preface

Strategic planners need to pay attention to corporate and legal documents that can delimit decisions needed to support strategic change. Corporate documents refer to the charter, bylaws, and mission statement of the college, while legal documents may comprise both explicit and implied contracts. Explicit contracts lay out duties and responsibilities for each party. An example of an explicit contract in higher education is a faculty contract, an endowment donation, or a third-party contract like an agreement with an enrollment agency. An implied-in-fact contract denotes that one party gains a benefit from another party, and a second party is expected to reciprocate the first party. Examples of impliedin-fact agreements include: student acceptance letters, catalogs, syllabi, academic schedules, student club rules, residence hall rules, and work assignments.

Corporate and legal documents are critical when a strategic plan intends to redefine the mission, reduce the number of employees, terminate academic programs, and implement new academic programs. The cost of failing to consider corporate and legal documents can result in a lawsuit that blocks the strategic plan, generates costly judgments and returns the college to its original state of swiftly moving to a financial collapse.

Corporate By-Laws and Charter

By-laws and the corporate charter establish rules that set out the authority and limits to govern the college. It is imperative that the corporate charter clearly state that the board of trustees retains final authority on policies, procedures, strategies, plans, and all matters related to institutional operation. If by-laws or the charter do not support strategic or operational plans, these documents must be revised and submitted to the appropriate state agency for review. If approved by the agency, it will issue the revised by-laws and charter.

Mission Statement

Mission statements frame what the college as a corporation intends to do. The best mission statements are short and to the point. For example, ‘the college provides curricula so that graduates can be either employed in positions generating sufficient income for a reasonable lifestyle or enter a graduate or professional program.

Board Resolutions

Board resolutions are decisions made by the board of trustees to assure that the college can deliver on its mission. Furthermore, records of board resolutions should be easily available to determine if current decisions are compatible with past resolutions or if a new resolution needs to resolve conflicts between current and past decisions by the board. Authority Authority is determined by state’s laws, corporate by-laws and charter, the mission, and resolutions of the board. Moreover, authority defines the scope of a position’s decision authority, and authority relationships across each level of the college. Notably, authority should clearly define who has direct access to the board on policies and procedures.

Boards should only establish independent entities that fall within the normal authority and responsibility channels of the college.

Handbooks

Handbooks, as noted above, are implied contracts. They often delineate job descriptions, processes, policies, communication channels, and expectations. Handbooks are not necessarily confined to employees and students. They can also cover relationships with third parties such as construction contractors, enrollment agencies, the alumni board or associations like sororities or fraternities.

Strategic plans may change handbooks by altering reporting relationships, work requirements, job descriptions, work-flows, decision authority, calendars, curricula, discipline codes, student clubs, student services, course requirements, and a broad range of other actions that may have to occur to implement the strategic plan.

Failure to review and revise handbooks can stop strategic implementation of a strategy in its tracks.

Board Cohesion and Financial Crisis

Board factions can deadlock decisions needed to avert a catastrophic financial crisis. During a financial crisis, expeditious action by the board is essential. Because action cannot be delayed, the board should request that the college’s attorney vet all proposals and also be available at board meetings to respond to board members who are apprehensive that a particular plan will fail the test of law.

Final Remarks

Boards of trustees and presidents must be cognizant of the constraints that corporate and legal documents place upon strategic and operational plans, especially, during a time of severe financial crisis. It is not unusual for some college board of trustees and presidents to be pushed to the wall by a series of deficits that rise from $10 to $20 million to $30 million over consecutive years. Colleges going through such disastrous financial crises usually have little time or financial resources to save the college. Only quick action that considers constraints imposed by its corporate structure and contracts can hope to slow the momentum to becoming another failed college. As a final note, these colleges can only be saved by a president with the foresight, will, and the experience to quickly formulate a strategic and operational plan that slows and, with good fortune, stops the momentum toward closure.

by Michael K. Townsley | Sep 19, 2024 | Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis, Strategic Planning

Failure Has Many Causes

Why are some colleges seemingly collapsing overnight? There are many causes for some private colleges surviving at the brink, but it takes a particular set of circumstances for a sudden collapse. What follows are factors that could drive a massive financial crisis. This list is based on research on financial collapse and interviews of leaders who passed through a cataclysmic financial crisis.

Elements of a Massive Financial Crisis

• The board of trustees miss signals that the college faces a financial catastrophe.

• The board needs to receive sufficient and accurate information about the financial condition of the college.

• Cash reserves are less than two months, and the next federal tranche is not expected to arrive until after cash is exhausted.

• Over-collateralization of property eliminates the college’s flexibility of selling property for cash.

• Handbook rules that prevent an immediate reduction-in-force plan or lead to ambiguity over who has decision authority over academic matters.

• Third-party enrollment contracts in which a contractor receives a portion of the tuition and fees from new students. A college with a high tuition discount rate, and if it is combined with the contractor’s rate, can find that it receives little or no cash out of new student tuition. For example, here is a case where a college discount has a discount rate of 75% and contracts with an enrollment agency that charges 25% of new student tuition revenue; this college will only receive 5% of new student revenue.

• Buildings that are empty and have been financed by loans. These buildings are a dead weight on the college’s finances.

• Very low student-faculty ratios result in a too expensive faculty and insufficient tuition revenue to support their compensation. Even worse, many colleges have low bars for tenure that makes it challenging to do a reduction-in-force or even to reduce their pay.

• Board meetings fail to have a quorum.

• Neither the president nor the board practice due diligence on plans or contracts.

• Neither the president nor the board involve legal counsel who is experienced in higher education law to vet strategies and operational plans.

• Either the president or the board chair or both publicly announce that they expect the college to close. The result is devastating. New students withdraw their applications, and donors stop giving to the college.