by Michael K. Townsley | May 25, 2022 | Strategic Planning

Executive Summary

Efficiency in higher education is an amusing topic that is best left to economists. The reality is that all constituents of a college or university know that the institution in inherently inefficient due to poorly designed operational policies, procedures, decision rubrics, resource allocations, and production of its main product – the education of students. Boards, administrators, and even regulators have either ignored operational inefficiencies or found them too intractable to change. Nevertheless, colleges and universities do graduate students and produce credible research, despite their awkward approach to delivering on their mission. However, the days of traipsing down the ivy-bedecked walls of alma mater are swiftly coming to an end. Efficiency will necessarily rise to a level of action due to complex combination of conditions like the Covid pandemic, inflation, shrinking new student markets, and students rejecting colleges charging high tuition prices to earn a degree with a low return on income. This blog will deal with the concept and framing of efficiency, managing efficiency in colleges and universities, bottlenecked operating chains, efficiency notes for presidents, and a brief comment on the relationship between financial equilibrium and efficiency.

Introduction to Efficiency

Nearly every college and university in the United States has the same operational structure and decision-governance process regardless of size, mission, or method of instructional delivery. The structure of higher education in this country has deep historical roots going back to Oxford and Cambridge in England with the design carried into this country with the founding of the early colleges such as Harvard. However, In America, the people of the state authorized the creation and to operation of colleges and universities through charters that provided ultimate responsibility and authority to a disinterested board. There has always been an assumption in the American system that the faculty’s domain is the curriculum and certification of successful completion of study. In the nineteenth century, presidents were much stronger than today. At that time, they were members of the faculty, with a primus inter-pares role. That system began to change during the twentieth century as presidents were less likely to be of and from the faculty and a dual organization system developed with a professional class led by the president and a faculty class with a counterbalancing role described most cogently by the AAUP. This dual organization structure has a significant flaw; it is resistant to change. Therefore, by extension, it is very expensive to operate because programs become embedded in the decision-governance process that often acted as a veto on change. This flaw became most evident when the nature of colleges changed from a rite of passage for only about 20% of the population (typically the traditional socially privileged and academically prepared student) to a pathway for social mobility and professional success for an additional 40% of less academically prepared and socially privileged post World War II students. This was accentuated especially as government sponsored financial aid programs expanded significantly, creating an environment of competition between colleges for an abundant market of students and the tuition they provide to support operations. The dual organization model worked reasonably well until that market began to decline and colleges had to act more strategically to adapt and compete. This created pressure to move from a dual organization governance system to a shared governance system that recognized more clearly the board’s role and authority. But that transition is not complete and many colleges are still ill equipped for change.

Due to the accelerating decline in enrollments that is combined with pressure to lower prices by way of tuition discounts and students insisting on degrees that lead to jobs in which their pay covers their debt payments and the cost of living, most private colleges and some private universities must now confront the impact of these conditions on the cost of operations. Solutions to these confounding problems of declining revenue (plus shrinking cash flows from tuition) and the cost of operations is the principal subject of this discourse.

Framing Efficiency

Efficiency or Productive Efficiency is the minimum cost for a particular level of output produced by a firm. Determining the relationship between cost input and output requires precise data. In higher education, precise data detailing costs and output is problematical on several levels. First, colleges do not clearly define the costs that drive a particular output. Moreover, they are often not clear about what the outputs are. Outputs can be classified as: credits, graduates, students enrolled in a program, full-time-equivalents, specific degrees, or credentials. As is evident from this imprecise list, several of the outputs may in fact be inputs; e.g., credits, students enrolled in a program, or full-time-equivalents. The confusion between inputs and outputs in higher education makes the problem of estimating productive efficiency very costly, difficult, and time-consuming. Nevertheless, given the declining demand for education and aggressive competition for new students, colleges and universities cannot ignore the problem of minimizing costs. While this discussion does not offer a mathematical solution to estimating minimal costs, we will suggest what can be done to improve the management of costs.

Managing Efficiency in Colleges and Universities

- Governance: Most colleges and universities operate within a dual governance structure in which the faculty has advisory authority over the academic program, the administration has authority over the rest of the college, and the Board of Trustees has authority over both. Conflict usually occurs at the edge between administrative authority and academic authority. There are two problems with dual governance that lead to cost inefficiencies. First, ultimate responsibility for survival of the institution is often not defined. Second, policies are often written in an ambiguous fashion regarding assignment of responsibility and expected outcomes. The literature suggests that ambiguous policies result from attempts to minimize conflicts of the dual governance divide. Eliminating existing and future policy ambiguities requires that the Board of Trustees fully understand which level is granted ultimate responsibility by law for the survival and integrity of the institution. If the Board does not understand this responsibility, they need training in their legal responsibilities, and they need legal counsel to review all policies and recommend changes to eliminate diminution of Board authority.

- Charter and Mission: The charter is the heart of the corporate entity and defines what it is allowed to do. The mission delineates what an institution can or cannot do. If the institution goes beyond its mission, it departs from its authority as granted by its charter. Therefore, significant changes in the activities of the college must be brought into conformity to its mission and charter or else both need to be amended.

- Academic Efficiency: This concept boils down to who controls the productive structure of the college; i.e., who has the authority to reorient academic operations in order to better serve students versus serving the status quo. Academic efficiency depends on 1) a leader skilled in revising the academic program in the face of intractable opposition and 2) an able lawyer in higher education labor law who briefs legal constraints for academic and personnel changes.

- Operational Efficiency: This concept depends on the proficiency of the president to a) identify if the college is responding to the demands of the student and job markets, b) restructure academic programs to attract students and prepare them for the job market, and c) allocate personnel and assets to best serve students at the lowest cost per student ratio. In addition, the president, in consort with the faculty, must have academic technical skills to revise or design the following: new curriculum; class schedules; information technology to deliver and administer academic operations; and the legal constraints on changes in programs. Moreover, the president must see how to efficiently utilize the physical space.

- Financial Efficiency is subject to these standards:

- Cash is essential for survival.

- Short-term assets need to be readily convertible to cash.

- For most private colleges, cash flows from enrollment and gift/donations.

- Operations must generate strong and positive cash flows.

- Monitor factors that deplete cash: rising tuition discounts; excess number of administrators and staff (too many administrators and staff doing the job that one person could); small enrollments in majors; small classes; capital and operational costs of buildings with low usage rates; and ineffective marketing strategies.

- Use dashboards and critical period performance reports to identify financial imbalances that cover: enrollment, class size, tuition discount, net tuition revenue, donations, cash balances, staff compensation, variable expenses, and unbudgeted expenditures

- Set-up and track these efficiency ratios:

- Net-tuition per student

- Receivable and bad debt ratios

- Net Donation/Advancement Officer

- Assets Efficiency Ratio – measure square feet being used against the space available in a twenty-four-hour time span.

- Market Efficiency: requires a) data by: student markets, yield rates, campaign target effectiveness, and enrollment by programs; b) best practices in reaching and drawing students from market segments; and c) continuous monitoring of marketing performance.

Bottlenecked Operating Chains

A bottleneck chain is a set of offices that are connected in carrying out a common set of processes. If these chains are not carefully designed, the result can be a process stream that becomes bottlenecked. A process stream is often bottlenecked at the interchange between offices. These bottlenecks can occur when process streams are not designed to carry from one office to another or when administrators do not work together in harmony.

Only the president has the authority and the responsibility to sort out the process stream and to eliminate inter-office conflict. In order to resolve bottlenecks, a president will have to get down into the nitty-gritty of policies and processes. That is, the president will be involved in analysis of a chain and will lead the redesign of chain policies and processes. Listed below are several critical chains typically found in an institution of higher education.

- Admissions Chain: Admissions – Registrar – Student Affairs (athletics, residence, food services) Financial Office – Bookstore – IT

- Continuing Student Chain: Registrar – IT – Academic Office (class schedule) – Student Affairs (athletics, residence, food services) – Bookstore – Student Affairs (residence/dining plans)

- Class Scheduling Chain: Academic Office –- IT – Student Affairs (athletics, residence, food services) – Registrar – Bookstore – Security

- Billing Office: Registrar – IT– Billing Office – Academic – Student Affairs (financial problems) –

- Payables Office: Academic Affairs– President’s Office – Chief Administrative Offices – Student Affairs – Faculty – Vendors

- Grades and Transcript Chain: Registrar – Faculty – Academic Office -Registrar – IT – Student Affairs (athletics, residence, food services)

- Student Affairs: Academic Scheduling Office, Athletic Office, Residence Halls – Food Services – Student Organizations

- Graduation Chain: Registrar – Academic Affairs – Student Affairs – Security

- Budgeting Bottleneck Chain: Finance Office – Budget Office – President’s Office – Academic Offices – Building and Grounds – Security – Board

Efficiency Notes for the President

The efficiency notes provide common leadership standards for a president as they guide their institutions toward greater efficiency. These are also final notes for other chief administrative officers.

- Communications supporting major decisions must be precise and comprehensive, especially when they involve a delegation of authority.

- Presidents must work effectively with the board and all constituencies of the college.

- Before the president and board initiate change, they should prepare for conflict, in particular with the faculty when it involves changes in academic programs, faculty policies, and assignments.

- Presidents need to understand the dynamics of the college and its basic operational processes. For example:

- Basic management doctrine – mission, responsibility, and outcome defined action.

- Financial resource allocations to departments, capital expenses, and personnel.

- Operational procedures, staff training and the expectation that administrators, staff and faculty will use administrative and academic software.

- Effective/efficient allocation of personnel are essential to survival.

- Paying market rates for skilled positions in academics, finance, and human resources.

- Recognizing that today’s shrunken student pools require the best marketing enrollment managers.

- How pricing (including tuition discounts) shape prospective student decisions in consort with their expectations of the outcome from their degrees.

- Need access to the best higher education legal services because change is usually constrained by laws (especially labor) and regulations (state and federal).

- Small college presidents may have to act like the head of a small business by doing the work of: writing policy and procedural manuals, curriculum design, academic scheduling, contracts, financial reports, and faculty and staff evaluation. The president needs to know the budgets of each department, financial reports and the dynamics of cash flows.

- Senior staff must understand the dynamics and processes of their area of responsibilities and this area to other domains and to the college as a whole.

Summary

Efficiency in higher education may be construed as being subject to Cyert’s model of financial equilibrium.[1] His model posits that financial equilibrium occurs when there are sufficient resources to sustain an institution’s mission for current and future students.[2] It could be said that a college’s financial equilibrium would be dependent on its efficiency in using its financial resources to sustain its mission. Inefficient use of resources would either deplete financial reserves or fail to convert incoming financial resources into productive units to accomplish the mission of the intuition. As a result, students would be ill-served by an inefficient college.

The culture of the college that has presently emerged is what has shaped the current state of efficiency in most institutions. It will be the responsibility of the board, administration, faculty and accreditors to increase the efficiency of the college by working together to reform policies, processes, and decision-making. Changes in the operational structure of the college will mainly take place through its governance system, which is morphing from the traditional dual governance model into a shared-governance model. Sound board and presidential leadership can make certain positive steps to good management and to greater operational efficiency.

ENDNOTE

-

Townsley, Michael (2014) Financial Strategy for Higher Education: A Field Guide for Presidents, CFOs, and Boards of Trustees; Lulu Press; Indianapolis, Indiana; p. 15. ↑

-

Townsley, Michael (2014) Financial Strategy for Higher Education: A Field Guide for Presidents, CFOs, and Boards of Trustees; Lulu Press; Indianapolis, Indiana; p. 15. ↑

by Michael K. Townsley | May 22, 2022 | Financial Strategy and Operations

U.S. Department of Education (DOE), credit rating agencies, banks, regional accrediting commissions, and boards of trustees want assurance of financial viability from colleges and universities. Different organizations have devised and adopted metrics that they believe are indicators of financial viability. For example, DOE uses a test of financial responsibility; Moody’s Investor Services applies a set of financial ratios; regional accrediting agency reports use audited statements and ratios or indexes recommended by the National Association of College and University Business Officials (NACUBO). The impact of financial metrics is to push colleges and universities to develop strategies and operational plans that produce financial results that conform to the measurements built into the metrics. This push seems to have picked up speed over the last decade as state and federal legislatures worry about the cost of a degree. As a result, they are pushing credit agencies, accrediting commissions, and boards to be more attentive to the financial condition of institutions of higher education.

Why do colleges and universities care about metrics established by third parties? The answer is simple these parties – government agencies, banks, accreditors – control access to resources. The consequences to a college that fails to measure up to third-party metrics could include the loss of authority to issue federal financial aid or a lending agency calling for full payment on loan balances. As a result, the college may be forced to substantially alter its way of doing business. Financial metrics coming from third parties are expanding in scope and rigor; and because of their impact on the existence of an institution of higher education, metrics represent powerful incentives for colleges as they design strategies and operational plans.

Basic Definition and Purpose of a Financial Metric

A financial metric incorporates two components – the metric and the benchmark for the metric. A metric can be generally defined as a measurement standard that sets out the performance level for a particular aspect of the finances of an organization. The metric may be a ratio, a rate of growth, or a particular number[2]. For instance, the metric may be the ratio of net income to total revenue, the rate of growth for total revenue compared to total expenses, or maintenance of an exact amount of money in cash reserves. The benchmark establishes the level of performance for the metric. The benchmark may be defined by government regulations, such as the DOE test of responsibility which specifies passing and failing scores. It may also be defined in terms of standard practice, such as the ratio of net income to total revenue should be greater than two percent or equal to greater than the rate of inflation. Another benchmark could be a metric defined in the covenant section of a debt instrument; for example a covenant may require a college to have cash equal to a portion of bond interest and principle that is available at all times.

The purpose of metric is to signify if performance is better than, less than, or equal to the benchmark, and to indicate if action must be taken to achieve the benchmark or restore the financial condition of the college to the level of the benchmark. Financial metrics exist to compel managers, or in this case college presidents and boards of trustees to take action to assure that they have strategies and plans in place to achieve the designated metrics for their institutions.

Positive and Negative Aspects of Metrics

There are positive and negative aspects to managing by metrics. The positive side is that CFOs and presidents know how external agencies will measure financial performance. The primary advantage of metrics is that they impose financial discipline on presidents, boards of trustees, and chief financial officers. Metrics represent a set of financial performance standards that an institution deems to be relevant to achieving or maintaining its financial condition.

While metrics can have negative consequences as will be noted later, they act as powerful guides as institutions make decision about budgets, capital investments, and fiscal management. When the leadership chooses a set of metrics to measure financial performance, they also accept the implied condition that their financial decisions must conform to the performance levels delineated by the financial metrics of their institution.

For the board of trustees, financial performance when compared to the chosen financial metrics can assure them that current financial strategies and plans are appropriate to strengthening the financial condition of the institution; metrics can indicate that the current financial strategy and plans are not working and a new financial strategy is needed. Using metrics is only useful if they are accompanied by a formal reporting system that compares actual performance to the metrics over time. In other words, the leadership of the institution must see the trend for each metric and if changes in the trend are favorable or unfavorable.

Given that metrics are only as effective as a reporting system that is taken seriously, the following also must occur:

- The president and chief administrative officers must formally meet, review performance, and determine if and where changes need to be made. By extension, they should prepare a brief formal document laying out the financial state of the college and any strategic or operational changes that are needed to achieve the performance level required by the metrics.

- The president must present the metric performance report to the board of trustees so that they can evaluate on their own if the plans are appropriate.

The negative side of metrics is that they can constrain the options available to a college, in particular, financially-weak colleges that are developing a new financial strategy. Metrics can limit a financially-weak college as they move from their current weak financial position to a stronger more viable financial state. During the transition, the metrics may show that the financial viability of the college is continuing to deteriorate before a turnaround strategy takes hold. An example would be a college that has reported deficits for several years because there is no longer a market for its academic programs.

This college needs to reallocate its resources and invest in new programs. As the strategy is implemented, the cost of the investment may be greater than the savings from a reallocation of and a reduction in staff and faculty. During this period, the financial metrics for the college will probably deteriorate, which could depress metrics and present problems with bank covenants, regulatory tests, and accreditors.

The other downside with managing to the metrics is that it could distort the priorities of the college. That is to say that sustaining the metrics may become more important than the mission of the college and the services designed to deliver on the mission.

Sources and Examples of Metrics

There are several sources for metrics and their associated benchmarks. In several cases, the metrics are required either through government regulation, debt covenants, or accreditation commissions. Other metrics may be selected by the institution because they represent industry standards that can measure financial performance. Benchmarks are either defined by regulation, set-out in debt documents, specified by accreditors, or generally available through published documents. The following list of metrics are commonly required or selected by colleges and universities.

- The U.S. Department of Education (DOE) test of financial responsibility [5] uses three ratios to indicate if the financial condition of the college is weak and needs to take action to substantially improve its financial condition. If test scores are below designated levels, regulatory guidelines can require the institution to post a letter of credit; or if test scores remain below levels over a number of years, DOE may no longer grant the institution the authority to award federal financial aid.

- The three ratios are:

- Primary Reserve (similar to CFI)

- Net Worth (net assets / total assets)

- Net Income (unrestricted net income / unrestricted revenue).

- The values for these ratios are adjusted by a set of strengths and weights; and the sum of these values yields the test score.

- Test scores less than 1.5 may result in regulatory sanctions.

- The Composite Financial Index [7] uses four ratios to measure the financial condition of private colleges and universities, as follows:

- Ratios:

- Primary Reserve Ratio measures operational risk with this relationship: expendable net assets to expenses

- Net Income Ratio measures short-term risk with this relationship: net operating income to operating revenue

- Return on Net Assets Ratio measures risk to production of wealth with this relationship: change in net assets to total assets

- Viability Ratio measures long-term debt risk with this relationship: expendable net assets to long-term debt.

- A CFI score less than or equal to three suggests that the financial condition of the college is weak, and it will need to take major steps to improve its financial condition.

- Debt Covenants are metrics in a loan agreement or debt indenture. Here are several examples:

- The condition that the institution not have deficits

- Cash income ratio[8], which relates: net cash from operating activities to total unrestricted income, excluding gains. Median values for this ratio are available in Ratio Analysis in Higher Education[9].

- Basic Financial Metrics are a set of metrics that an institution may employ to measure factors that have a direct impact on the financial condition of the institution. These metrics may include:

- Net tuition ratio – Measures tuition revenue remaining after deducting unfunded institutional aid. The issue is, if this ratio is changing over time, the ratio is: total tuition and fees revenue minus financial aid to total tuition and fees revenue.

- Receivables ratio – Measures proportion of net tuition and fees that are receivables, The issue is, if this ratio is changing over time, higher ratios suggest less cash is being collected; the ratio is: net student receivables to total tuition and fees.

- Bad debt ratio – Measures the proportion of receivables that is bad debt. The issue is, if this ratio is increasing over time, it suggests that the institution is unable to fully convert receivables to cash; the ratio is: uncollectable receivables to student receivables.

- Deferred maintenance ratio[10] – Measure potential burden of deferred maintenance. The issue is, if this ratio is increasing, the institution is incurring an ever increasing burden on its financial assets to restore its buildings and equipment to the proper state; the ratio is: outstanding maintenance requirements to expendable assets (the denominator is the same as the numerator for the Primary Ratio in the CFI).

- Financial assets ratio – Measures the proportion of assets devoted to financial assets. The issue is, if this ratio is declining, then the institution is potentially losing the capacity to support its operations from endowments; the ratio is: net investments and cash to total assets.

- Endowment performance – This metric is the annual rate of return for endowment assets. The issue is the same as with the financial assets ratio.

- Enrollment growth – This metric is the annual rate of growth for enrollment by level and by program. There are multiple issues: is enrollment growing, shrinking, or remaining by level, and by program? Any significant shifts could have financial effects.

- Average class size – This metric measures total average class size and average class size by full- and part-time faculty. This metric is a rough measure of the efficiency of class scheduling and the constraint imposed by room capacity.

- Compensation per student – Since compensation makes up more than sixty per cent of the expenses at most colleges and universities, it is important to know if that burden on students is increasing, decreasing or remaining level. Compensation is a sum of the total salaries, benefits, and taxes, which include social security, Medicare, and other special employment taxes that the institution may have to pay. The following ratios measure the relationship of compensation to students for major functions of the institution:

- Administrative compensation per student

- Faculty compensation per student

- Academic affairs compensation per student

- Student services compensation per student

- Institutional compensation per student.

Summary

Financial metrics should support the analysis of equilibrium and development of plans to achieve a state of equilibrium (see Chapter XIII) and strategies and plans flowing from using the financial paradigm (see Chapter XII) to efficiently use the financial resources of the institution. Financial metrics should be seen as the web which ties together financial strategies and the plans that should strengthen the financial viability of the institution.

|

Take Away Points

- CFOs must do more than manage to net income.

- Financial management should cover critical metrics for assets, liabilities, net assets, cash, net income, and debt covenants.

- Financial strategies and budgets should be tested against the metrics.

- Annual reports should compare performance to metric benchmarks.

- The president, CFO, and chief administrators should immediately formulate turnaround plans for those segments of the college that failing to achieve their metric benchmarks.

- The college administration should have the authority and the responsibility to manage to the metrics.

|

Endnotes

-

1988; Cave, Martin, Stephen Hanney, Maurice Kogan and Gillian Trevet; The Use of Performance Indicators in Higher Education; Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London; pp: 17-18 ↑

-

2004; Financial Aid Professionals: Methodology for Regulatory Test of Financial Responsibility Using Financial Ratios; (September 29, 2004); (Retrieved November 1, 2010) http://www2.ed.gov/finaid/prof/resources/finresp/finalreport/execsummary.html ↑

-

2005; Salluzzo, R.E., Tahey, P., Prager, F.J., & Cowen, C.J.; Ratio analysis in higher Education, 6th edition published by KPMG, LLP & Prager, McCarthy & Sealy, LLC; pp 94-99 ↑

-

2005; Salluzzo, R.E., Tahey, P., Prager, F.J., & Cowen, C.J.; Ratio analysis in higher Education, 6th edition published by KPMG, LLP & Prager, McCarthy & Sealy, LLC; p 109 ↑

-

2005; Salluzzo, R.E., Tahey, P., Prager, F.J., & Cowen, C.J.; Ratio analysis in higher Education, 6th edition published by KPMG, LLP & Prager, McCarthy & Sealy, LLC; p 109; p 124 ↑

-

2005; Salluzzo, R.E., Tahey, P., Prager, F.J., & Cowen, C.J.; Ratio analysis in higher Education, 6th edition published by KPMG, LLP & Prager, McCarthy & Sealy, LLC; p 109; p 81 ↑

by Michael K. Townsley | May 22, 2022 | Enrollment and Marketing

NACUBO Warns – Enrollments May Be Declining with Tuition Discounts

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

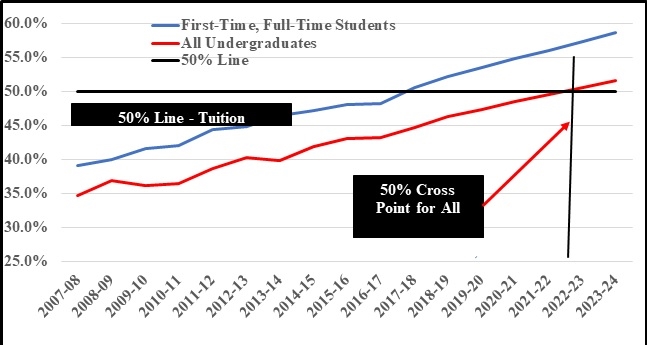

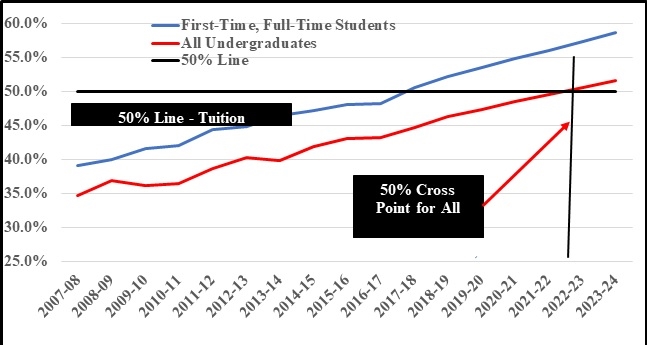

NACUBO just published its survey of tuition discounting and the results are disturbing. For the first time, a number of private colleges reported that new student enrollment declined despite increases in a tuition-discounting program. Over the past several decades, tuition discounting strategies have provided private colleges with a mechanism to increase tuition by 2% over inflation while deflating the increase for new students through higher tuition discounts.

When tuition discounting strategies stop working, new student revenue drops and net tuition revenues fall below expectations. Failed discounting strategies will quickly undermine the budgetary and financial stability of many private colleges.

There are two possible reasons that may explain why tuition discounting strategies are losing their punch. The first is based on the underlying economics of discounting strategy and the second is possibly due to diminishing returns with tuition discounts. This blog will talk about why the economics may be changing and how the tuition discount algebraic expression could accelerate the problems with lost net tuition revenue.

Economic Premise Underlying Tuition Discounting – Price Inelasticity

The basic economic premise underpinning tuition discounting is that students are price inelastic. This means that if discounts do not reduce tuition below the previous year’s tuition rate, an increase in tuition will not result in a loss of student revenue. More than likely, if the new tuition level leads to a drop in new student enrollment, it will be small and the higher tuition rate will offset the loss.

Why are students’ price inelastic? Students in the past have not been price shoppers. They tend to pick a college based on hearsay or recommendations from friends or family. Also, students have not needed to shop around because tuition could be paid from savings or discretionary income or, if they borrowed money, they did not accumulate large amounts of debt. Also, until recently, students finished their degree at the college where they first enrolled. They did not transfer elsewhere because transferring credits was too difficult and their personal investment in their own academic credits and social network were too high to forego.

When tuition discount strategies were well-behaved (as in Chart I), enrollments grew and total tuition revenue increased. Presidents and Chief-Financial-Officers counted on tuition strategies to produce anticipated patterns of tuition income flow, which led to budgetary and financial stability.

Chart I

Well-Behaved Discounting: Tuition Net of Inflation (0%). Annual Increment (5%) and Discount (base year discount: 42% with annual tuition increment of 1%) Compared to the Net Tuition Rate

Are Students Becoming More Price Elastic?

Recent evidence suggests that students and their parents have become aggressive shoppers looking for the best price. As colleges ease their rules in accepting transfer credit, they are encouraging students to continue to shop for the best deal, be it price, academic programs, sports, or amenities, even when they have already enrolled and earned credit. The best deal may encompass more than price. One of the unexpected outcomes, with the increasing probability of transfers, is that colleges are forced to deal with both new students and keeping their currently enrolled students. Shopping by both new and enrolled students suggests that price inelasticity is waning as students become more price elastic. Greater price elasticity will distort the customary tuition discount strategy of jacking up tuition prices then discounting it to new students. Price elasticity suggests that higher tuition levels will drive students to find cheaper alternatives and that they may prefer easily understood posted prices rather than complex financial aid packages.

The Tuition Discount Formula Contains a Kicker

The tuition discount strategy typically has two components, a rate of change for tuition and a rate of change for tuition discounts. As price inelasticity wanes and is replaced by greater price elasticity, a quirky aspect of the tuition discount strategy rears its ugly head.

When price elastic conditions prevail, tuition discount strategies incorporate a kicker. The kicker becomes apparent because static enrollment no longer masks the tendency of the tuition discount to produce diminishing returns and negative dollar changes. This perverse aspect of tuition discounting is readily evident in Chart II.

Chart II

Hidden Kicker: Tuition Net of Inflation (3%), Annual Increment (5%) and Discount (base year discount: 42% with annual tuition increment of 1%) Compared to the Net Tuition Rate

Under the inflationary, incremental tuition, tuition discount, and static enrollment conditions in Chart II, posted tuition has a nice positive slope. However, net tuition rate exhibits an alarming negative slope. As price elasticity takes hold, more colleges will find that as the enrollment mask is stripped away, net tuition rate will generate diminishing returns. By implication, diminishing returns for the net tuition rate will carry through to diminishing returns for net tuition revenue. Chart III clearly illustrates how marginal changes (diminishing returns) have a very steep and negative slope. Presidents and Chief Financial Officers need to be worried about diminishing returns when tuition discounting strategies stop working; i.e., enrollment no longer increases as net tuition rates increase over time.

Chart III

Effect of the Hidden Kicker on Marginal Change in Net Tuition

Private Colleges Should Take Prudent Steps to Build New Financial Strategies

For years, private colleges have been able to have their cake and eat it too by raising tuition faster than inflation and then partially reducing the impact through tuition discounts. If tuition discount strategies are losing their capacity to generate new net tuition revenue, then it is prudent that private colleges, especially financially weak institutions, consider alternatives to the classic tuition discount strategy. Moreover, government and media criticism about rising posted tuition charges only adds pressure to colleges to find new ways to fund the delivery system for education without depending upon never ending increases in tuition rates.

What Should Colleges Do If the Tuition Discount Strategy Is Becoming Obsolete?

Private colleges will need a different perspective if they intend to develop new funding strategies and to deal with governmental oversight on tuition prices. Here are several strategies for managing tuition pricing that Stevens Strategy has implemented with our clients.

- Responsibility Centered Management (RCM) Analysis: this service identifies programs that generate sufficient net income to support the general operation of the institution. This analysis can be the basis for developing expense allocation strategies, cost controls, and new income producing programs.

- Programs and Resource Optimization (PRO): adds mission centeredness and quality and marketability reviews to the RCM analysis.

- Operational Cost Analysis: this service pinpoints cost efficiencies and inefficiencies.

- Financial, Marketing, and Operational Reviews: Stevens Strategy works closely with the President and Chief Operations Officers to review current financial, marketing, and income production strategies, practices, policies, and operational systems to determine if they support the mission of the institution, generate adequate income, and provide a smooth-running cost-effective operation.

- Financial Health Checkup: this service involves a thorough evaluation of financial conditions both short- and long-term to determine if financial stability is improving or declining.

- Equilibrium Analysis: this service focuses on the strategies needed to achieve economic equilibrium given known economic, financial, regulatory, competitive, and operational conditions.

Stevens Strategy recommends that Presidents and Chief Operational Officers conduct a careful review of their institutional discounting strategies, plans, and performance data. Our firm can assist you in conducting the review and provide recommendations on changes that may need to be made to manage and control tuition and discounting strategies.

by Debra M. Townsley | May 22, 2022 | Strategic Planning

Debra Townsley, author of articles on strategy and presidential leadership and Michael Townsley have a new book – Colleges in Crisis. The central theme of this book is that the massive decline forecast for prospective college students over the next decade will push many private colleges to and over the brink of survival. The book looks to answer this question ‘What strategies can Presidents and Boards of Trustees apply to confront this crisis?’

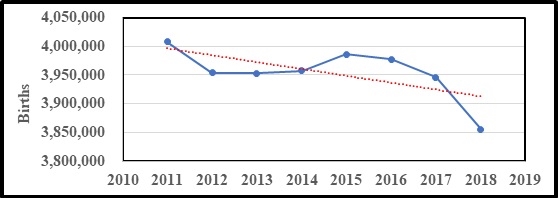

The book covers: the decline in enrollment due to a collapse of the birth rate that is amplified by high cost of loans and the decline in liberal arts enrollment; inherent conflict within institution governance structure that delays strategic changes, and ways institutional leaders can move forward with strategic changes.

Section 1: Enrollment – Shrinking Demand

-

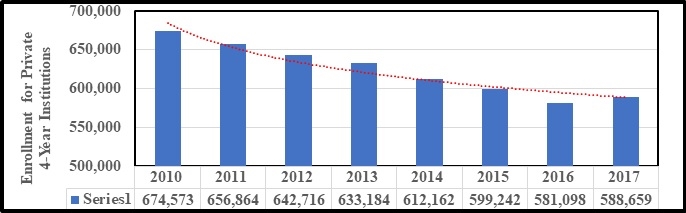

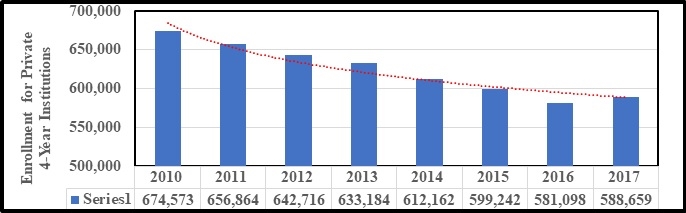

- Current state of enrollment for Private 4-Year Institutions 2010 to 2017

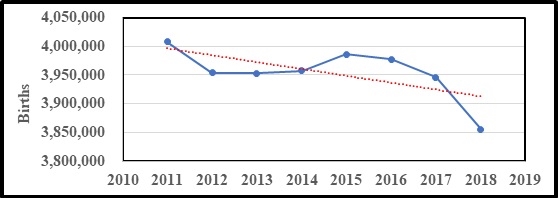

- Birth Rates from 2010 to 2019

- Investment in Education Hindered by Future Cost of Debt

Anna Maria Andriotis, Ken Brown and Shane Shifflett in a 2019 article in the Wall Street Journal reported that:

“The American middle class is falling deeper into debt to maintain a middle-class lifestyle. Cars, college, houses and medical care have become steadily more costly, but incomes have been largely stagnant for two decades,. [1]

-

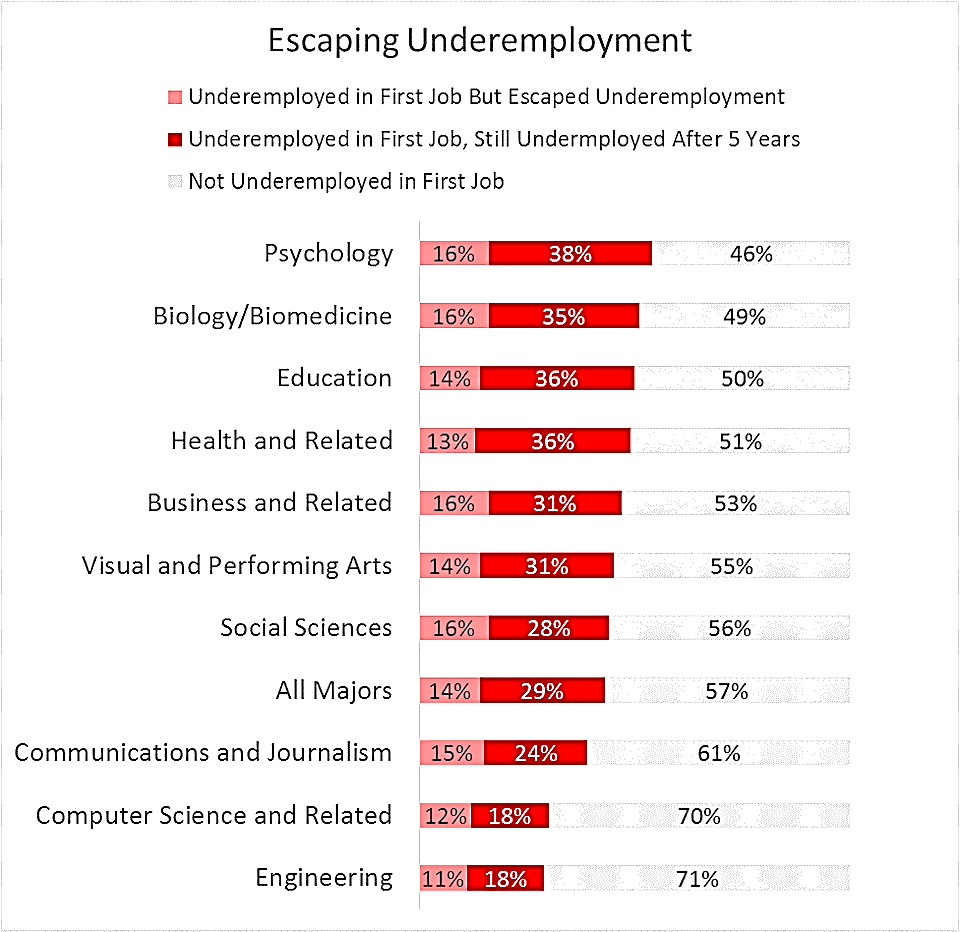

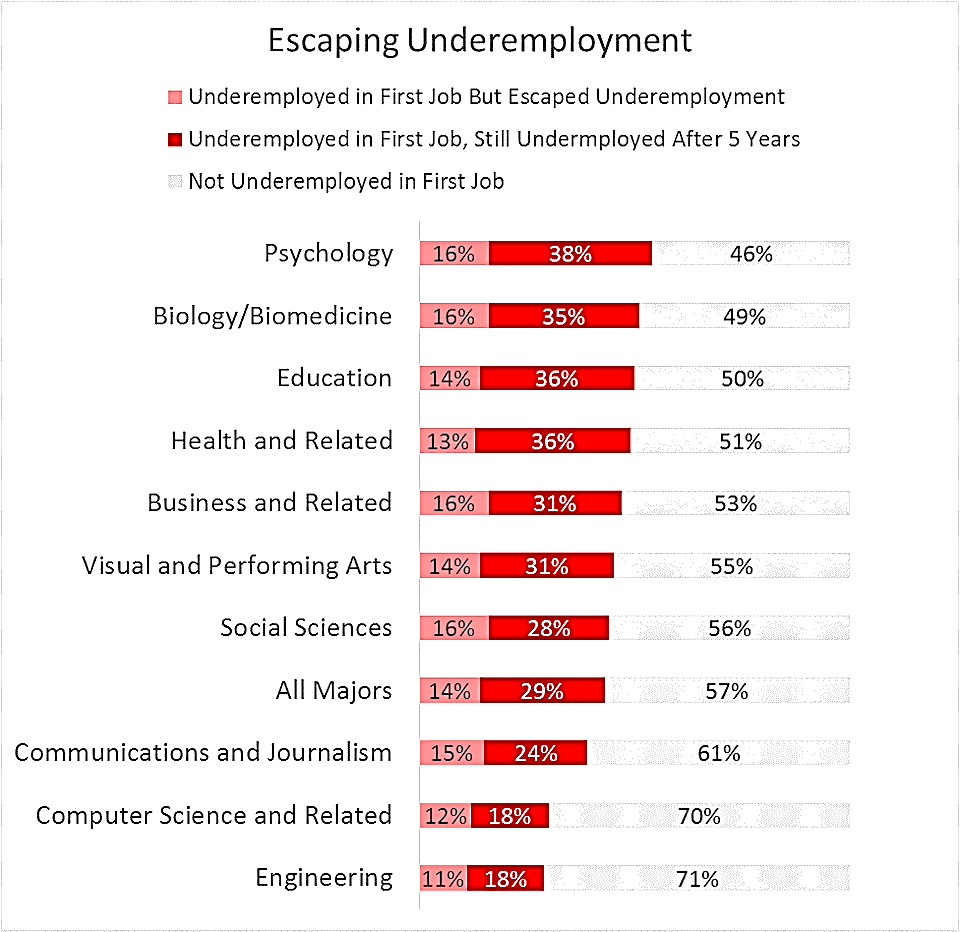

- Shifting Preference for Academic Majors[2]

-

- Price Competition – Tuition Discounting [3]

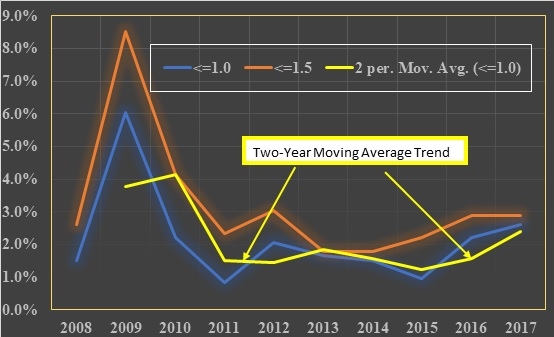

Section 2: Private Colleges are Sliding into Financial Distress

-

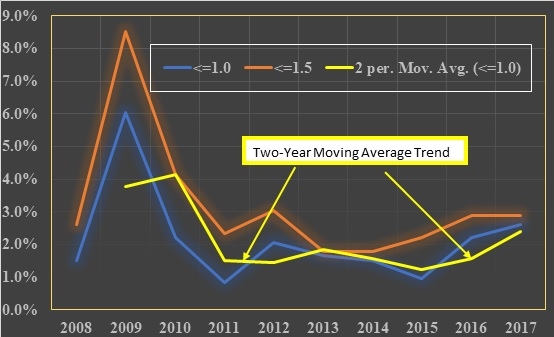

- Percentage of Not-For-Profit Colleges Reporting Financial Distress Under the Department of Education’s ‘Test of Financial Responsibility’” for the Period: 2008 to 2017[4]

-

- Institutional Averages: Full-Time Equivalent Students, First-Time, Full-Time Equivalent Students, and Total Expenses: Period 2010 to 2017[5]

|

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

Compound Rate |

| Total N of Institutions |

242 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| FTE |

1,615 |

1,614 |

1,607 |

1,596 |

1,584 |

1,572 |

1,563 |

1,549 |

-0.59% |

| FT-FTE |

414 |

410 |

406 |

407 |

405 |

403 |

405 |

401 |

-0.45% |

| EXP (000) |

$62,620 |

$64,267 |

$66,713 |

$68,531 |

$70,258 |

$72,109 |

$74,174 |

$75,363 |

2.68% |

Section 3: Causes of Resistance to Strategic Change

-

- Contradictions of dual authority governance systems

- Faculty tenure

- Political model of decision-making through interest group subverts hierarchical decision-making

- Constraints imposed by accreditors and regulators

- Legal constraints – explicit and implied

- Mismatch between human and tangible capital investment and the student market

Section 4: Strategic Options to the Coming Demographic Crash

- Leadership Rubric of Change

- Comprehensive Strategic Phased Planning

- Partnership and Merger Options

Target for Publication: January 2020

- Endnotes:

Androitis, Ann Marie, Ken Brown, and Shane Shifflet (August 1, 2019); “Families Go Deep in Debt to Stay in the Middle Class”; Wall Street Journal; https://www.wsj.com/articles/families-go-deep-in-debt-to-stay-in-the-middle-class-11564673734. ↑

- Cooper, Preston (June 8, 2018/); Underemployment Persists Throughout College Graduates’ Career”; Forbes Magazine; https://www.forbes.com/sites/prestoncooper2/2018/06/08/underemployment-persists-throughout-college-graduates-careers/#547d9a087490. ↑

- “Private Colleges Now Use Nearly Half of Tuition Revenue for Scholarships (May 9. 2019); NACUBO. ↑

- “Federal Student Aid (Retrieved October 16 ,2019); “Financial Responsibility Scores”; Office of the U.S. Department of Education; https://studentaid.ed.gov/sa/about/data-center/school/composite-scores. ↑

- John Minter & Associates (August 8, 2019); Data Extracted for a select set of colleges from the 2017 Data Set – Integrated Postsecondary Education System. ↑

by Michael K. Townsley | May 22, 2022 | Presidential Leadership

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

Presidents and chief administrative officers need to develop a fine hand at delegating authority. The blog on Scarce Resources speaks to the limited amount of time and energy that the top level administrators have. If the president tries to do everything for everyone else then nothing will be done well because mistakes will be made as strategic initiatives and projects are rushed or put aside and forgotten because there is not enough time. The same problem exists for chief administrators who do not develop the skill to delegate authority.

For some reason, many higher education leaders are reluctant to delegate authority. If and when they do delegate work, they might give imprecise instructions because they give them verbally. Too often the delegation takes place in a passing conversation. The leader making the delegation assumes that the delegation is understood even though the person receiving the delegation may or may not have understood what was said but is reluctant to ask for clarification. The result is a botched delegation and what was done or not done does not meet the expectations of the leader. Eventually, leaders just dive in and do it themselves, and they have fallen into the trap of expending their scarce time and energy resources on something that could have been done by someone else.

Before we lay out the rules of delegation, we need to define what delegation means. Project delegation occurs when someone is given authority and responsibility to complete a specific project or task within a specified time period. With this type of delegation, when the project is completed, the assigned leader’s position comes to an end. Examples of project management would be the development of student flow procedures from admissions, registration, academic services, to graduation. The reason for this blog is to provide presidents and chief administrative officers with a template for managing the process of delegation for a short-term project.

This blog will lay-out basic rules of delegation for short-term projects. Effective delegations of authority should have a Statement of Delegation that lays out authority, control, communications, participants, and funds available for managing the project. The rules for delegating project management are described below.

- Major sections of the Statement of Delegation:

- Description of the project

- Objective of the project

- Project Leaders authority and responsibility

- Report and Management assignment of a Chief Administrative Officer

- Handoff of the project to operational managers, if appropriate

- Project Leaders name

- Colleagues assigned to the project work team

- Time line

- Budget

- Reports

- Project Description Section: a brief two or three sentence description of the project and its purpose

- Project Objective: what the team is to accomplish and by when

- Project Leaders Authority: the authority that the Project Leader is assigned to accomplish, coordinate, control, and resolve conflicts

- Report and Management: assign a Chief Administrative Officer (or the President if the Project Leader is a Chief Administrative Officer) to supervise, review, and resolve obstacles or problems that delay completion of the project

- Handoff: how and when the project becomes operation

- Project Leaders Name and Colleagues – names, email addresses, and phone numbers

- Time Line: specifies when the project starts, when reports are due, and a date for completing the project

- Budget: refers to funds assigned to complete the project

- Reports: list the type of reports needed to show progress and to whom the reports are sent

Delegation is only effective when the chief administrative officer (or the President) who supervises the Project Leader meets regularly with the Leader to review progress, problems and cost. If these supervisory meetings do not take place, there is a good chance that the project may fail to accomplish its objective or meet its deadlines. Delegation is an interactive process that calls for a continuous flow of information between supervisor, project leader, and colleagues participating in the project.