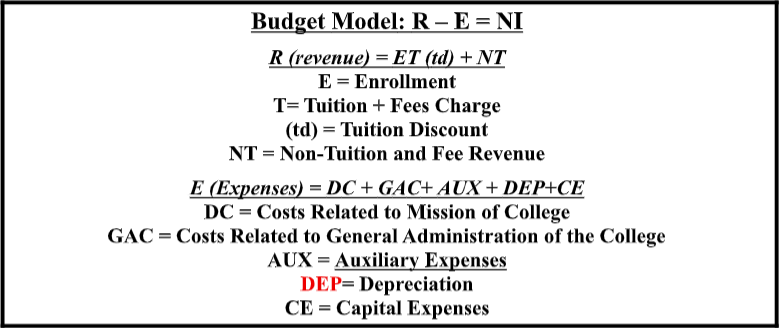

This simple budget equation captures the major factors that drive the on-going financial condition at most private colleges and universities. The conundrum for the president, chief financial officers, and other chief administrators is the degree to which they do or do not have control of the budget variables.

Budget Model

The budget model is a straightforward linear equation with easily recognizable variables that drive the outcome net income. However, the values that feed the variables make the model idiosyncratic for each institution. In the past, the model was a finely tuned instrument intended to set tuition that students can afford, fund its operations, and maintain its solvency. Owing to the large number of closed or merged colleges and cancelled academic programs, the budget that is based on the current structure, policies, and academic programs is having greater difficulty finding: a tuition price that works for the student and college, funding its operations, and maintaining solvency.

Budget Model Balancing Mechanism: Revenue, Expenses, and Net Income

The budget model depicts the balance as changes take place among– revenue, expenses, and net income. The following table lays out typical changes in revenue expenses, and net income.

|

Revenue |

Expense Decisions |

Net Income |

|

If revenue increases |

Expenses could increase |

Net could decrease, remain stable, or go down. |

|

If revenue decreases |

Expenses could increase |

Net would go down |

|

If revenue remains the same |

Expenses could remain the same |

Net could remain the same |

|

If revenue remains the same |

Expenses could increase |

Net would go down |

Because private colleges are dealing with significant threats to their cash reserves, the budget model variables and values should be construed to estimate the impact of the budget on cash reserves. Therefore, depreciation would not be included in the model because depreciation is a non-cash transaction. As a result, net Income should be equivalent to positive or negative changes to cash reserves. Obviously, this caveat does not account for non-cash variables or values such as, depreciation. While the primary goal of the budget model is to estimate the cash effect of budget decisions, it would be prudent for the college to test the budget impact on the audit version of net income by including depreciation.

Richard Cyert and the Budget Model

Before the discussion on the budget equation begins in earnest, let us consider what Richard Cyert, a leading organizational theorist, and the late president of Carnegie-Mellon University, developed the concept of Economic Equilibrium,[1] which is a state of long-term financial sustainability that rests on the following principles[2].

- There is sufficient quality and quantity of resources to fulfill the mission of an institution, and

- The organization maintains:

- The purchasing power of its financial assets.

- Its facilities in satisfactory condition.

Cyert’s theory posits that equilibrium depends on continuously increasing cash flows from operations to maintain the purchasing power of its operating financial assets and sufficient capital gifts to keep its facilities in satisfactory condition. Colleges need a dynamic state of economic equilibrium in which financial resources grow to avoid a state of disequilibrium; i.e. budgetary outcomes that puts a private college a risk of slipping into insolvency. An institution can no longer assume that positive but small changes in net income and financial assets are sufficient to stave off disequilibrium.

When an institution’s financial condition has eroded to the point where its cash and financial reserves have been seriously depleted, developing a strategic plan to achieve a dynamic state of equilibrium is difficult. Easy decisions, such as raising tuition or simply cutting expenses across the board, can be counterproductive if it pushes the college outside its competitive boundaries[3]. As Richard Cyert noted, “the trick of managing the contracting organization is to break the vicious circle which tends to lead to disintegration of the organization. Management must develop counter forces which will allow the organization to maintain viability.”[4]

Cyert’s proposition about economic equilibrium implies that it is imperative for colleges to retune their budget model to maintain or regain equilibrium. Keep these comments in mind, as the revenue, expense, and net income factors that make-up the model are examined.

To reiterate, the purpose of this paper is to gain a better about the budget equation and the factors that drive the equation.

Revenue Factors

Revenue provides the funds to support operational costs to carry out the mission of the college. The revenue factors discussed below include: enrollment, tuition and fees, tuition discount, and non-tuition revenue

Enrollment (E)

Enrollment, as anyone who works in budget planning well knows, is not a simple sum of all the students in the college. The nuances are myriad. Here are several aspects of enrollment that need to be considered.

- Recalling that this is a budget exercise, enrollment is subdivided based on the price charged for a particular segment of enrollment. For example:

- Undergraduate students typically are charged a different tuition than graduate students,

- Part-time students are either charged at a fixed rate depending on how part-time status is defined; or on sliding rate depending on the credits taken;

- On-site classes may have a different rate than on-line classes;

- The price-enrollment categories are endless. Obviously, any degree of complexity in the price-enrollment requires precision in accounting for the different enrollments so that enrollment and accounting records can be reconciled.

- Besides the price-enrollment dynamic, enrollment is subject to student demand for the college, graduate outcomes, its programs, reputation, location, and schedules. Student preferences have changed dramatically since the COVID pandemic and changes by employers in the type of skills that they seek from college graduates. Now, a growing proportion of prospective and enrolled students want a degree that directly related to their probability of finding employment that provides both a loveable wage and cover the costs of living and debt service for their education.

- Moreover, prospective students seek more information from social media about colleges and their outcomes. As a result, the old enrollment strategy of traveling to high schools to find students is now a minor tactic compared to current dynamic and sophisticated student marketing campaigns.

- The Enrollment Cliff has wrecked the old new student strategy of needing just a few more to make budget and sustain financial operations. Because of the Cliff private colleges now live in a state of anxiety because they cannot find students to match current enrollment let alone keep pace with costs by enrolling additional students to

Tuition and Fee Charges (T)

- Economics of tuition and fee charges – they are the price that mediates student market demand and the supply of colleges programs. Because of the demographic cliff combined with too many colleges offering similar programs, colleges have lost their capacity to control tuition and fees. Under these conditions, price – tuition and fees – should fall. Since most of the discussion about tuition is about the posted price, real price declines have been missed. For years, analysts have pointed out that tuition discounts reduce the posted price and over the past several years, real tuition has been falling dramatically as tuition discounts increase. (see the later discussion on tuition discounts to understand the impact of rising discounts on a college’s financial stability).

- Howard Bowen.[5] in the 1980s expressed skepticism about the apparent business principle in which expenses drove tuition and fees. The implication of their skepticism is that at some point private colleges and universities would lose that luxury in which tuition and fees could be pressed forward without any consequences. It is now evident given the tight constraints that college face when adjusting tuition charges that their incredulity was justified.

- Colleges have been able to game tuition constraints by increasing fee rate and by adding new fees. This game will not work well during a time of pinched student financial resources.

- Colleges no longer face an ignorant student market with few choices, parents and students have become savvy price negotiators, which has transferred pricing power from the institution to the student.

Tuition Discount (td)

- A tuition discount is an unfunded institutional scholarship that reduces the price of tuition. Because the scholarship is unfunded, the college does not receive offsetting cash from endowed funds as it would with a funded scholarship or a government grant. This means that as unfunded tuition discounts increase, cash decreases and the capacity of the college to cover its existing cost structure is diminished, which increases its risk of failure.

- The financial crunch, in which colleges try to maintain economic equilibrium during a period of severe decline in student markets, change in student preferences away from existing majors, and, as will be noted below, decisive cuts in federal funds is putting greater pressure on colleges to increase tuition discounts. The problem is, as indicated above, that every uptick in tuition discounts cuts into the cash needed to support operations and throws colleges into economic disequilibrium.

Non-Tuition and Fee Revenue (NT)

- The sources of Non-Tuition and Fee cover grants, gifts, endowment draws, auxiliary revenue, and any other revenue not related to tuition. Just a note on endowment draws, since median draws is about 5% of the endowment, a $1 draw $20 of endowment. This relationship requires a large endowment to have any real impact on the budget. Because most private colleges do not have large enough endowments or the prospects of substantially increasing their endowments, this source of revenue remains a minor player during a time of financial crisis.

Further Notes on Revenue in the Budget Model

- For the average private college, enrollment driven revenue is the primary source of funds that drive the outcomes of the budget model.

- For most new and continuing students, the price of enrollment is made palatable by federal aid, funded institutional scholarships, and unfunded scholarships. Any significant negative changes in federal and funded scholarships can adversely affect a student’s decision to enroll. In addition, when colleges try to minimize the effect of shrinking federal aid or strong price competition by increasing tuition discounts, too often the financial viability of the college is threatened.

Expenses Factors

Expense factors delineate the way in the categories in which funds are allocated to carry out the mission of the college. The expense factors discussed below are: direct costs, general administrative costs, depreciation, and capital expenses.

Direct Costs (DC)

Direct costs include: instruction; student services, academic support, and other costs associated with delivering educational services to students. NB. This discussion does not include research because private colleges with large research budgets usually have a different budget dynamic.

General Administrative Costs (GAC)

General administrative costs encompass: institutional administration (president’s office, insurance, utilities, and like costs that relate to all segments of the college), building and grounds, and other general administrative costs that are included in the audit under institutional expenses.

Auxiliary Costs (AUX)

Auxiliary costs cover the cost of running: residence halls, food stores, book stores, and any other peripheral operation that is deemed by the college as auxiliary to the main purpose of the college and generates auxiliary income.

Depreciation (DEP)

Depreciation is the annual accounting charge against net physical assets, such as, buildings, grounds, and equipment. Depreciation should not be included when estimating cash generated from net income.

Capital Expenses (CE)

Capital expenses usually involve interest payments on debt.

Notes on Expenses

Multiple conditions usually constrain the flexibility of budget planners in what they can easily cut during a financial crisis: tenure, employment contracts with long-term commitments, debt, location of classrooms, utilities, contracts with third parties, zoning restrictions on the use of property, and restrictions on the use of endowment funds, engineering limits on buildings. Each college often has unique conditions which limit a college’s flexibility during a financial crisis.

Net Income (NI)

Net income is simply what remains after expenses are deducted from revenue. If the goal of the college is to reach Cyert’s Economic Equilibrium, then the college must focus on the Net Income in terms of the cash that it produces.

The Balancing Act

- Typically, when a college intends to resolve financial stress by using the Cyert Criteria of Economic Equilibrium, it must continuously Net Income shows positive cash flow. Then, the rebuild cash reserves and any loans from the endowment within two to three years? If the budget model falls short in resolving financial distress, then the college must work harder to reduce costs, find new sources of income, and convert assets to cash.

- Debt covenants, such as, the requirement not to produce a string of deficits, can force a college to make large expense cuts that would dimmish the college’s capacity to serve its mission.

- Debt collateralization occurs when a college grants rights to property to a debt holder to secure a loan. During a financial crisis, collateralized property may not be sold without the debtholders’ permission. Moreover, even if they can sell the property, the debtholder could tell the college that the proceeds from the sale go toward reduction of debt principal.

–

-

Cyert, R. (July, August 1978); The Management of Universities of Constant or Decreasing Size; Public Administration Review; p. 345. ↑

-

Competitive bounds refer to a matrix with price and quality as axes of the matrix. A specific market is depicted as a smaller square within the matrix which includes potential students who prefer to enroll at a specific college with a particular level of price and quality. ↑

-

Bowen, Howard C. (1981) The Costs of Higher Education; Jossey-Bass; San Francisco; pp.18-20. ↑