by Michael K. Townsley | May 22, 2022 | Presidential Leadership

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

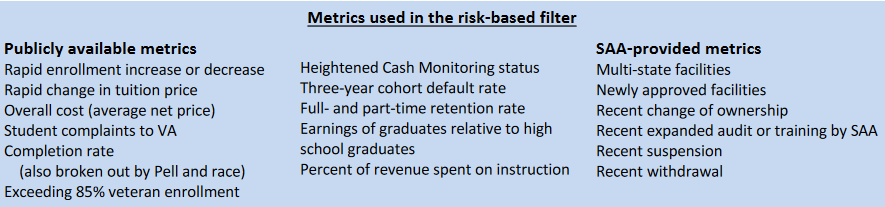

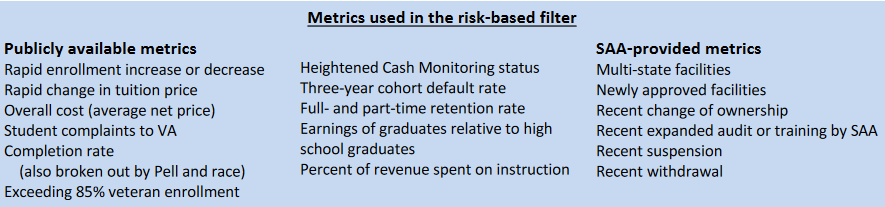

The February 2, 2022 issue of Inside Higher Education carried the article “Using College Outcomes to Gauge Risk for Students” by Doug Lederman. [1] The article addressed how to protect veterans from choosing a college that might not survive. The article reviews several measures to identify the potential signs that a college might fail. This blog will comment on assumptions of the underlying measures of college survival and the validity and construct of those measures. The article includes these “metrics used in the risk-based filter.”

The article does point out a fundamental political question raised by Rebecca S. Natow, Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy at Hofstra University:

“She said via email that an accountability regimen that applied to all colleges and universities …would struggle to gain the sort of bipartisan support that measures about veterans do.

The two main political parties have been much less likely to agree on accountability policies affecting Title IV programs more broadly, such as the gainful-employment rule, Natow said. It could be brought about through executive action, as much federal policy making in higher education has been [recently], but that typically results in legal challenges and flip-flopping as a new administration takes office.

Leaving matters in the states’ hands, in contrast, typically results in vastly uneven regulation, with some states being rigorous and others less so, Natow said.”

Moreover, another broad assumption is that government bureaucrats would enforce regulations to constrain risk. Instead, bureaucrats might determine that the greater risk is to themselves because enforcement could see the demise of institutions that are supported by powerful interest groups and by formidable political leaders. One example of this phenomenon of non-enforcement of risk regulations is that year after year the same colleges fail the Department of Education (DOE) ‘Financial Responsibility Test,’ yet the DOE rarely takes action.

General Comments: This section covers several significant sources of inefficiency.

- Managing risk in higher education assumes that colleges are attuned to factors that increase risk and that they have the power to control them.

- An important problem with nearly every metric and model of risk is that they are not rigorously tested to evaluate if they are valid. Too often the models are victims of post hoc analysis because they don’t take into account colleges that have closed.

- Of course, the main question regarding risk is how to define risk in higher education. Richard Cyert provides a way into understanding that risk. According to Cyert, a college needs to reach a state of economic equilibrium to assure its long-term survival. According to his model, financial equilibrium occurs when there are sufficient resources to sustain an institution’s mission for current and future students.[2] Therefore, risk would be the probability that the financial resources of an institution could or could not sustain the academic program (assuming that academic programs are the primary mission of the institution) for current or future students.

Comments about Risk Metrics and Models:

- Risk metrics are burdened by the inherent problems associated with the excessive aggregation of institutional data that limits the capacity to clearly identify issues below the broadest institutional levels. In other words, because refined data is not available, models and metrics too often assume that available and overly aggregated data will be valid predictors of risk.

- Over the past several decades, financial risk has been measured by importing business ratios. The assumption is that business ratios can capture the financial condition of an institution of higher education. However, business rates are designed to measure risk in terms of the capacity of the enterprise to generate sufficient cash flow to sustain on-going operations. Colleges, on the other hand, can and often survive for decades on the cusp of financial disaster as measured by business ratios because annual gifts, new government funds, or donors who make large gifts repeatedly pull an institution’s chestnuts out of the fire.

- Even though some colleges have survived for years as mere husks of an institution of higher education, these institutions often fail to achieve Cyert’s equilibrium condition that colleges need sufficient resources to support their mission and to serve their students for the short- and long-term. When colleges are merely husks, they too often may produce a degree with little or no value to graduating students.

- Certain risk-filter models hypothesize that they can forecast grave risks using seven or more years of long-term data for predictor variables. The problem with these models is it they assume that the predictor variable is continuously downward sloping. While these models may identify some institutions at risk, they often miss many institutions where early data may be positive, and then due to external or internal conditions, the predictor data suddenly turns negative. Regrettably, the adverse effect of a short-term and hazardous decline in a predictor variable may be dampened by earlier positive performance using long-term data. The best way of testing a risk-filter model is to test it against a data set that includes institutions that have already failed. Sadly, this data is often hard to locate because when institutions close, they are no longer identified in data sets.

Risk Based Filter Metrics Included in “Using College Outcomes to Gauge Risk for Students”

The following table is from the Inside Higher Education article, which includes risk metrics that were being considered by the Veterans Affairs Administration to protect veterans from enrolling in a failing college. These metrics are also commonly found in other risk models. After the table, there are several comments about the Veteran Affairs metrics suggesting which metrics are the most and least valuable.

The following risk-based factors are of modest or no value in determining short-term risk:

- Rapid enrollment increases or decreases: This metric is used in risk models and financial reviews, because for most private colleges and universities enrollments are the main drivers of revenue. If the period to measure the change in enrollment is too long, the change within the period may mask real problems in a shorter time frame. Change in enrollment is a worthwhile metric only when compared to changes in direct expenses (instruction, student services, and academic support).

- Rapid change in tuition price: this measure is an insufficient measure of risk because it does not get at the price paid by a student. The metric Overall Cost does measure the cost to a student.

- Completion rate (by Pell and race): This is a pertinent measure for government agencies to determine if their investment in a college is producing value for veterans. Moreover, prospective students may choose not to enroll at an institution with high attrition and low graduate rates. This measure is not a valuable risk metric of short terms risk because it requires data collected over a long period of time.

- Exceeding 85% VA enrollment: This metric is a VA regulatory measure to limit funding to an institution that mainly focuses on veterans, but it does not measure risk of institutional failure.

- Three-year cohort default rate: The presumed default rate is on federal loans. The underlying assumption is whether prospective students will continue to enroll if they graduate with loan balances that cannot be paid from their income. This metric might be useful in the long-term assuming that prospective students take earning after graduation into account when they agree to loans. However, the effect of the three-year cohort metric may become evident only after the college or university is already about to close due to other factors.

- Earnings of students relative to high school graduates: This metric is both an institutional and an academic program issue. The question is: “What is the point of enrolling in a program if a degree has no more (or even less) value than a high school diploma?” This issue is also germane to institutional marketing efforts. Assuming that future earnings from an institution or a program are known to prospective students, many will reject the choice if future earnings are insufficient to cover future expenses, as was noted in the default rate comment. This metric would be useful in analyzing programs in a long-term analysis, but it may have little practical value as a measure of short-term institutional risk unless all or most of the institution’s programs have little relative economic return in comparison.

- Percent of revenue spent on instruction: The assumption here is that as the percentage of money for instruction decreases, the quality of instruction also decreases. However, innovations in instructional delivery can reduce costs and increase quality. Instructional expenses can decrease at colleges that allocate more funds for student services and academic support to improve retention and graduation rates. ‘Percent of revenue spent on instruction’ as a risk metric is too limited.

- Note that the SAA metrics are mainly of interest to accreditors or government agencies and are not discussed here.

The following risk-based factors are of effective value in determining short-term risk:

- Overall Cost (average net price): This metric represents the out-of-pocket costs that veterans are being charged. If the metrics in the table are intended to measure risk, then this metric can illuminate the cash flowing from enrollment to cover direct costs. Multi-year evidence shows that while tuition net of institutional grants has fallen (in other words, students are paying less out of pocket), direct costs have been increasing. This means that the risk to the institution is increasing as net tuition declines and direct costs go up.

- Student complaints to VA: This is a good way for the VA to identify problems because the complaints are coming directly from students enrolled in a college or university.

- Heightened cash monitoring status: This metric gets at the central issue of whether an institution can survive. If a college or university does not have sufficient cash reserves to cover on-going operations and debt-service, then they may have to turn to lenders for short-term loans. If short-term loans increase in size over time, then the institution is at risk when unexpected events like the Covid pandemic occurs.

- Full and part-time retention rates: As retention rates fall, the need to find new students to bolster enrollment, along with associated marketing costs, increases. In addition, there is a possibility that falling retention rates imply that the academic programs are not designed to reach the academic skills of the students enrolled by the college. This metric also ties into the discussion about ‘Completion Rates’.

Several Other Metrics That Measure Risk Effectively:

Here are several risk metrics that could be used independently or assembled into a model:

- Net Student Revenue: If the sum of tuition net of institutional grants plus auxiliary income (excluding hospitals) and net of expenses is increasing, Net Student Revenue yields more funds for operations, while shrinking Net Student Revenue reduces capacity to support operations, which places the institution at risk.

- Net Student Revenue to Direct Expenses (instruction, student services, and academic support) Ratio: An increasing Net Student to Direct Expense Ratio is able to support a greater proportion of direct expenses or even produce excess revenue to cover indirect costs (ex. institutional support, plant, debt, etc.). A decreasing ratio reduces the proportion of funds available for direct funds and puts pressure on the college to find other sources of revenue, which is often not possible for tuition dependent colleges, thus placing the institution at risk.

- Class Size Ratio (the average number of students in front of an instructor): The larger the class size the greater the net direct instructional revenue and the smaller the class size the lower the net direct instructional revenue, increasing institutional risk.

- Class size in classes required by a major: Very small class sizes indicate that the major is not supporting the operational costs associated with the major. The greater the number of these underutilized majors, the greater the institutional risk.

- Net Tuition Revenue plus grants to Operational Costs of a Major Ratio: A small or declining ratio suggests that the major is unable to support itself. The more the number of these majors, the greater the institutional risk.

- Space Usage Ratio: This ratio measures the percentage of building space used during a fully employed period of sixteen hours. A low usage ratio suggests that building space is not fully optimized to cover debt service, operational costs, or repair and maintenance, and is an indicator of future risk.

- Cash Flow Metrics: As indicated in the preceding section under the heading “Heightened cash monitoring status,” cash is a common metric in measuring risk. Here are several ways to measure if the college is building or depleting its cash reserves:

- Cash Flow from Operations: This metric is found in audit reports and shows cash is the main reserve from which operations are supported.

- Cash from Operations to Net Change in Assets from Current Operations: This measures whether operations are increasing or depleting cash.

- Total Cash: This shows if the college is building its cash reserves from all sources of cash. It also measures if trends in total cash are increasing or decreasing.

- Negative cash trends are a definite indicator of future risk.

Risk Management – Preserving the Mission

If risk is defined by Cyert’s proposition that colleges risk their capacity to deliver on their mission if they do not have sufficient financial reserves, then the question arises: “How does an institution reduce its risk?” Colleges and universities can reduce risk by determining whether or not their mission is achievable given the resources that they have available. This proposition suggests that the following questions need to be addressed:

- What is the mission of the college?

- Does the mission fit the demands (expectations of students)?

- Does the mission need to be reconstrued to respond to the student market?

- If the mission needs to be rewritten, will the corporate by-laws support the change in the mission or do the by-laws need to be modified?

- Do academic programs need to be revised to respond to the expectations of students?

- Should resources, both fiscal assets and personnel, be reallocated in response to changes in the mission and academic programs?

- Ought the administrative footprint and physical assets be restructured or eliminated to release resources toward instruction and instructional support?

- What is the enrollment and net tuition price point needed to generate the funds needed to operate new academic programs and build financial reserves?

- How should marketing strategy and actions be redesigned to support changes in the mission, enrolled students, and academic programs?

There are many more questions that may need to be answered to perfect models of risk. Nevertheless, the economic environment reshaping higher education today makes it necessary to address these questions sooner rather than later.

ENDNOTES

-

Doug Lederman; (February 2, 2022) “Using College Outcomes to Gauge Risk for Students”; Inside Higher Education; A possible model for identifying riskiest colleges for students (insidehighered.com). ↑

-

Townsley, Michael (2014) Financial Strategy for Higher Education: A Field Guide for Presidents, CFOs, and Boards of Trustees; Lulu Press; Indianapolis, Indiana; p. 15. ↑

by Michael K. Townsley | May 22, 2022 | Financial Strategy and Operations

Chief financial officers (CFO) are gatekeepers for the financial resources that fund the mission of the institution. CFOs are more than a necessary evil to keep the money straight. They have a keystone role in the institution because their education, experience, and responsibilities give them unique insight into the quality and quantity of resources needed to support the mission. Their fundamental obligation is the management of the financial resources of the institution. How CFOs carry out this responsibility is the theme of this blog.

The chief financial officer and the president have complementary authority and responsibilities that reach into every corner and touch every person in the institution. While the president leads the institution to accomplish its mission, the CFO is charged by the president and the board with supporting the institution’s mission by judiciously allocating its scarce financial resources[1]. This charge expresses a duty that the CFO is responsible for assuring that funds are used for their intended purpose as designated by donors, or as required by governmental regulations, or as directed by the board of trustees. The CFO also has a fiduciary duty to maintain the integrity of the institution’s financial resources so that current and future generations of students can attain the benefits promised in the mission statement. Due to the CFOs’ fiduciary duty and certain governmental regulations, he/she may be held responsible for any wrongdoing in how government funds are expended or reported.

The CFO is seen by some as a miracle worker, who has secret treasures where money can be brought forth to save the college. Others see this person during a financial crisis as the expert who can explain exactly what happened as though it was his/her decisions that led to the crisis. Then there is the deep wonderment of colleagues who see accounting as an arcane science designed to confuse laypersons, which in turn makes the CFO a high priest of financial magic. Obviously, these are flawed conceptions of the position of the chief financial officer. Nevertheless, “… there is a real values tension between the business function, with its emphasis on pragmatic accountability, and the academic function, with its emphasis on knowing, teaching, and learning[; ]… the CFO must learn to manage this dynamic tension…[to perform her/his duties] [2] . As will be seen throughout this blog, CFOs have a significant role with the board of trustees, president, the academic community, and other chief administrative officers in negotiating, allocating, administering, monitoring, and developing strategic plans and financial resources.

Readers will find that while the work of the CFO is arduous and has a jargon of its own, it is worth the time to learn how the chief financial officer works because it builds a common understanding of the possibilities and constraints of the institution’s financial capacity, which shapes strategic and management plans. This understanding is especially important when colleges and universities confront perilous financial times and as new challenges emerge from government regulations, demographics, technology, and the markets.

The significance of the chief financial officer’s position to an institution is also evident by the fact that regulators, lenders, and accreditors require that the monetary transactions and practices of the business office be audited annually. No other area (administrative or academic function) of a college or university has its decisions audited annually. When serious problems occur, a CFO often finds that the board, president, and others expect him/her to take responsibility for the failure and explain why it happened, even though the CFO may not have had authority or responsibility for the problem.

Annual audits and the burden of managing the financial resources of a college may explain why a CFO is sometimes seen as the designated “naysayer and grumpiest” person on campus. Yet many CFOs have a remarkable ability to say no and do it in a fashion that carries the respect of the campus community without eliciting recriminations or distrust. The latter are the paragon that all CFOs aspire to be.

As the preceding suggests, the CFO is not a trivial position given the range of decisions for which they have the authority to act, the responsibility to comply with statutes and regulations, and the task to carry out the mission of the institution. This chapter will briefly examine how a CFO supports the mission, strategy, and management of her/his institution, and why and how she/he seeks financial equilibrium.

CFO – Where They Work

The next two tables show the distribution of CFOs by type and size of colleges. It is interesting to note that when the distribution is by size, the order is from large institutions (greater than 2,000 students), to medium (between 1,000 and 2,000 students), to small (less than 1,000 students). When institutions are classified by degree levels of institution, the order of distribution for CFO is first at baccalaureate institutions, then doctoral institutions, and lastly at masters institutions.

Table I

Chief Financial Officers

Count by Degree Level and Size of College[3]

Table II

Chief Financial Officers

Distribution by Degree Level and Size of College[4]

The ordering by degree level and size is probably linked to the career path of most CFOs. It is probable that 61% of them will spend their careers in a baccalaureate college where the main financial issue is likely to be accounting for the flow of revenue from tuition revenue or endowments to expenditures and on to the assets or liabilities. For those who work at a small college, these CFOs will spend most of their career worrying about enrollment trends and student revenues.

CFOs working at large institutions, given the likely progression of responsibilities, probably started within the business operation of a large institution and moved up the ladder to CFO. This progression is valuable to the institution because the CFO learned business operations where tuition, endowments, gifts, grants, and investments are almost certainly several dimensions more complex than at a baccalaureate college. The trend in higher education is to apply the title chief business officer (CBO) rather than CFO. However, the title is not critical to understanding the work of the CFO/CBO. Nevertheless, as will be seen immediately below, the two titles are valued differently in terms of compensation.

If there is a difference in real economic value of CFOs among the different degree-level institutions, it should be reflected in compensation. Table III (source: College and University Personnel Association (CUPA)[5] suggests that chief business officers are more valuable than chief financial officers and that CBOs are more valuable if they are employed at a doctoral institution rather than at a master’s or bachelor’s college. One reason for the difference in values of the two positions is that the chief business officer has broader responsibilities than the chief financial officer as defined in the CUPA survey. A CBO, according to CUPA, has responsibility for financial and administrative functions, while a CFO has responsibility for the financial function[6]. If the relationship between economic value and complexity of work responsibilities are valid in the case of business or financial officials, then it would make sense that compensation would be greater at a doctoral institution. Chief business/financial officers at these institutions deal with multi-faceted revenue and expense flows that carry stringent regulations and require intricate operating systems to plan, manage, and monitor to assure efficient and correct receipt and use of funds.

Table III

Chief Financial Officers

Compensation[7]

While financial issues at large institutions are at a greater scale than other levels, it is not necessarily true that the problems of masters and baccalaureate institutions are easier to solve. In fact, the latter colleges may be tuition-driven and exist in a world of very limited resources where financial stability is uncertain and where long-term planning is secondary to yearly survival[8].

CFOs – Competencies, Characteristics, and Preparation

CFOs are one of the few chief administrative officers that do not come up the ranks of the faculty to achieve their position. They may come from auditing firms, accounting departments in public businesses, or business offices in other colleges. This path to the position of the CFO can be a source of conflict with the faculty and other administrators because the person holding the position is not familiar with the intricacies, conflicts, and traditions of academic governance. As a result, the CFO may be viewed as ill-suited to discuss matters of institutional strategy, academic budgets, and other items that do not directly concern the accounting function. In some instances, even their accounting responsibilities are under question within the realm of academia.

The CFO in most circumstances is expected to possess a very specific set of competencies. If they do not bring these competencies to their job, not only are they and their job at risk but so also is the college. This list of competencies covers these areas:

- General accounting practice

- Accounting and financial reporting

- Accounting rules from the Federal Accounting Standards Board (FASB) or Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB)

- Preparation and management of budgets

- Tax rules applicable to higher education and tax reports

- Supervision of business and financial office functions

- Procedures and practices of debt financing

- Oversight of investments.

The characteristics of a particular CFO will depend on the type and size of their corresponding institution. Commonly, the large private and public institutions expect their CFOs to be well-versed in their field and are to have broad work experience in business and financial offices within comparable institutions of higher education. Medium-sized private and public institutions may be the stepping stone toward a larger institution. However, the institution may still expect the CFO to have enough business office experience so that she/he understands the expectations and constraints that shape her/his business operations. Smaller institutions, because they often cannot afford the top dollar costs of CFOs with long experience in business management or in higher education, will take larger risks than large- or medium-sized institutions and will hire a CFO with little experience or one just out of auditing practice.

The background of a CFO usually follows a familiar pattern – bachelor’s degree in accounting, maybe a master’s degree in business or accounting, and a Certified Public Accountant (CPA) license. These particular educational experiences for the CFO are not fancy wrapping but are essential to doing their work. Their educational training can be long (up to five years) and expensive, all before they can even sit for the CPA examination. A future CFO’s first job is usually low-paying and is in an auditing firm or a business office, as time in these types of jobs is typically required to earn a CPA license

CFO Job Description – Just What Do They Do?

CFOs in most institutions have authority and responsibility over accounting systems, budgets, budget controls, purchasing, cash management, debt management, internal and external financial reporting, tax reports, and financial analysis[10]. In some instances, they may be in charge of investments, or, if not directly in charge, they at least have the duty to accurately record investment transactions. A CFO is also an advisor to the president, board, and other chief administrative officers on financial strategy and budgets and the impact of revenue and expense decisions on short- and long-term financial viability.

The basic function of the CFO is to manage every financial transaction of the institution no matter the size, which is circumscribed by the chart of accounts, internal standards, practices, and policies, and by the budget structure, which is then subject to Generally Accepted Accounting Practices (GAAP). It is the resulting flow from transactions that either expand or deplete the financial resources of the institution.

Transactional records provide the infrastructure on which the financial statements, financial management, and financial strategies rest. When transactions are consistently and accurately recorded, financial reports will reliably reflect the current financial condition of the institution, both its weaknesses and its strengths. Financial reports are critically important to the president, board of trustees, and chief administrative officers because these reports underpin financial decisions related to long-term strategies and operational plans. Accurate and reliable financial records and reports are the very essence of the work of a CFO.

CFOs – Why They Are Held Accountable?

CFOs are held responsible for their decisions by tough accounting standards, by regulations, and by the expectations and oversight of the board of trustees and presidents. Accountability is established through annual audits by a neutral third party, i.e., a certified public accountant (CPA), who conducts a rigorous review based on GAAP principles of financial transactions, decisions, and reports. The purpose of accountability is to assure users of financial data (such as boards of trustees, presidents, banks, debt holders, government agencies, and accrediting commissions) that the data are reliable, are accurate, and are in compliance with accounting standards.

The reason for harsh sanctions and for rigorous monitoring of the financial operation is that the CFO has the sole responsibility for maintaining the financial resources of the institution given that the board and other chief administrators have made prudent and reasonable plans to employ those resources. The CFO’s singular duty is to husband the scarce financial reserves of the institution to finance the survival, reputation, and quality of the institution for current students, for future generations of students, and for the alumni. If not caught in time, reckless inept, or misfeasance in financial operations can devastate an institution’s financial reserves that may have taken decades to accumulate and could take decades to rebuild.

Two simple anecdotes will suffice to show what happens when a CFO has the misfortune of making a glaring and costly error or when a CFO, working with the president, has the perspicacity to solve a historically-knotty financial problem. The first case will show how a CFO vainly tried to grow the endowment using a risky investment strategy. The second case is about a college where deficits slowly burned away its financial reserves, and the college was rebuilt through the wisdom of a new CFO and a new President.

The first case involves a small college where the CFO had responsibility for investing the college’s endowment funds. In 2000, when the technology bubble was expanding geometrically, the CFO placed the college’s endowment in a high-flying technology mutual fund. She/he made a classic mistake made by naïve investors – she/he bought high and sold low – very low. Within one year, the mutual fund lost 80% of its value, effectively wiping out the endowment. An annual audit might have caught this problem, but the error played out within a single fiscal year.

The second story relates how a new CFO discovered that the previous CFO and president had masked deficits for many years while consuming its cash reserves. The board of trustees had abrogated their fiduciary responsibilities and had accepted financial reports that had created an illusion of financial stability. The CFO and the new president had the unwelcome task of telling the board that the wonderland world of finance was untrue and that the college was near financial collapse.

The CFO and the new president realized that they had to quickly put into place a financial strategy which would quickly end the college’s long history of deficits. The first year of the new financial strategy explicitly forecast a deficit, but the plan was based on new enrollment strategies, expense cuts, and budget controls. Within five years, their efforts were rewarded because the college rebuilt its cash reserves, which permitted the college to begin renovating its infrastructure and investing in existing and new academic programs.

The first tale is a horror story, while the second seems too good to be true. However, happily for most colleges, the second story is typical of the contribution that a good CFO, working closely with the president, can make to restore financial viability by providing financial resources so that the president can implement his/her vision of how to turn the college’s mission into reality.

CFO’s Contribution to Mission, Strategy, and Management

Good colleges and universities use the mission as a compass that guides strategy and management within the constraints of their financial resources. This guiding principle requires good CFOs, who assist the president, board of trustees, and chief administrators in finding the right application of financial resources in order to achieve the mission of the institution. The right direction in financial management requires the right balance between expanding and using financial resources to develop and produce credible educational programs that serve the college’s mission but do not deplete its financial reserves. Getting direction and balance right requires a CFO who has the financial, management, and personal skills to support a college to provide the right services to enhance the lives of its students without sapping its strength with petty rules and demands.

Expanded Role of CFOs

Most CFOs do more than sit at their desk like Dicken’s Bob Marley in a green eyeshade with quill in hand noting dollars in foot-high ledger books. Of course, this statement is an exaggerated description of the modern CFO, who usually is responsible for more than finance. The typical CFO is titled as Vice President for Administration (VPA), which takes in finance, building and grounds, auxiliary services, outsourced services, security, human resources, and whatever else the president and/or board of trustees assign to them. The degree of aggregation of the CFO’s responsibilities is usually related to the size of the institution and historical nature of the function at the institution.

When a CFO is also a VPA, their workload may divert them from their main task of financial strategy and management[13]. The result is that in some cases the main job – finance – is given short shrift or squeezed while problems are addressed in residence halls, dining halls, security incidents, maintenance problems, and contractual issues. It is an especially gifted person who can take on the duties of a CFO cum VPA. That is why colleges and universities, when replacing a CFO/VPA, should pay for the best. Buying cheap is a false economy because lackluster leaders can have long learning curves resulting in a delay in introducing change or making sure that financial management stays on course.

The premise of paying for the best CFO also applies to staffing the business or financial office. While the college may save a few dollars hiring untrained people to do basic work in those offices, too often lack of training and ability leads to egregious and costly errors. Errors, when they are not eliminated and are large, may result in a loss of confidence in the business office and the reports that it produces. Credibility is a continuing and elementary prerequisite of every CFO and the business office that she/he supervises.

CFOs as Agents of Financial Equilibrium

The primary economic goal of the CFO is to find the point of equilibrium for the operational income flows of the institution given that its financial resources cannot remain static over time. The importance of this goal lies in the need for institutions to continually add income in response to inflation and to build reserves to maintain facilities and to respond to unforeseen events.

There is a misconception that not-for-profit colleges and universities operate under a zero net income constraint in which they can only generate enough revenue to cover their immediate expenses. If net income is zero, they would be like many small businesses that quickly fail because they are undercapitalized. Undercapitalization simply means that they would not have sufficient working or long-term capital to protect them against unexpected turns in the economy, changes in student markets, and tougher competition. Moreover, zero net income would continue to limit instructional efficiency to the size of the average classroom. A classroom of twenty to thirty students is not an efficient way of distributing the high costs of faculty. Colleges need to reach an equilibrium level where net income flows are large enough to maintain instructional operations while allowing for technological changes, higher demand for highly skilled workers, or shifts in demand by parents and students for comfortable habitation, athletic facilities, and other expensive amenities.

The main point is that equilibrium is not static but dynamic; changing in response to student demand, flow of gifts and income from endowments, internal costs, competition, financial markets, governmental regulation, accreditors, and other forces that dictate the financial condition of an institution. Dynamic equilibrium suggests that the CFO will not find a single point in which growth of costs cease, financial resources stay vibrant, and external forces have no impact on the institution. Given the fallacy of this premise, a CFO must seek an equilibrium strategy that dynamically responds to continuous changes from internal and external economic and financial forces that wreak havoc with the status quo. Developing and managing an equilibrium strategy is the most difficult challenge faced by most CFOs because they must work closely with the president to convince the board of trustees of the importance of reaching a state of equilibrium. Then, the CFO and the president must work with all sectors of the institution to develop and follow-through on a feasible and dynamic equilibrium strategy. Equilibrium will be discussed in further detail in a later chapter.

Final Comment

The chief financial officer’s position cannot be fully described within the limits of this blog because the importance of a CFO for a particular institution depends upon the characteristics of the institution, its unique place in the market for higher education, and the full set of responsibilities assigned to the position. As noted earlier in this blog, in many instances, the CFO is more than a finance officer; she/he may also have responsibilities for building and grounds, auxiliaries, security, parking, copying and printing, and whatever else others either do not want to do or a president feels that the CFO is best fitted to do. Nevertheless, you will find in the balance of this blog a nicely drawn picture of the work of the typical chief financial officer as it pertains to the finances of an institution of higher education.

Endnotes

-

West, Richard P. (2001); The Role of the Chief Financial and Business Officer; College University Business Administration; National Association of College and University Business Officials; Washington, DC; p. 1 ↑

-

West, Richard P. (2001); The Role of the Chief Financial and Business Officer; College University Business Administration; National Association of College and University Business Officials; Washington, DC; p. 2 ↑

-

Minter, John (2010) Private CFO.xlsx; John Minter Associates; Oregon ↑

-

Minter, John (2010) Private CFO.xlsx; John Minter Associates; Oregon ↑

-

2009-10 CUPA – HR Administrative Compensation Survey; Unweighted Median Salary by Carnegie Classification; CUPA – HR Surveys; College and University Professional Association for Human Resource Resources; Knoxville, TN; (May 14, 2010); http://www.cupahr.org/surveys/adcomp_surveydata10.asp ↑

-

2009-10 Administrative Compensation Positions; CUPA – HR Administrative Compensation Survey; College and University Professional Association for Human Resource Resources; Knoxville, TN; (Retrieved May 14, 2010); http://www.cupahr.org/surveys/participate.asp ↑

-

2009-10 CUPA – HR Administrative Compensation Survey; Unweighted Median Salary by Carnegie Classification; CUPA – HR Surveys; College and University Professional Association for Human Resource Resources; Knoxville, TN; (Retrieved May 14, 2010); http://www.cupahr.org/surveys/adcomp_surveydata10.asp ↑

-

Townsley, Michael (1991) Brinksmanship, Planning, Smoke and Mirrors; Planning for Higher Education; 19(4): pp. 27–32. ↑

-

West, Richard P. (2001); The Role of the Chief Financial and Business Officer; College University Business Administration; National Association of College and University Business Officials; Washington, DC; pp. 10-14 ↑

-

West, Richard P. (2001); The Role of the Chief Financial and Business Officer; College University Business Administration; National Association of College and University Business Officials; Washington, DC; p. 17 ↑

by Debra M. Townsley | May 21, 2022 | Strategic Planning

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

Scenario:

Assumptions and Conditions

Before we talk about the Transition Principles, I want to sketch out a small scenario about interviewing and taking a presidency at a college in need of a turn-around. The characteristics of the institution I present is not built upon any single college and, despite all the hoopla about Sweet Briar, none of the conditions are taken from that particular college. The institution in this scenario are located nearly seven hundred miles to the west of Sweet Briar.

The major premises of the scenario are: first, you would like to work at the college; second, you believe that you have the skills and experience to deliver a successful turn-around strategy; and third, you have sufficient due diligence background information to prepare for the interview.

What You Could Encounter at the Interview for a Turn-Around

If we assume that the board recognizes that a turn-around is needed, it does not necessarily mean that they are willing to do the heavy lifting required for a turn-around. Here are a few comments that have been heard over the past several years from board members:

“We (the board) believe that we can grow out of our current financial problem.”

This came from a college that needed five hundred new students in the next fiscal year to solve their problem. They would have needed to increase enrollment 50% in the next fiscal year. If they staged the turn-around over several years, they would have to had enrolled even more new students because the deficit was growing at a 20% clip annually. The belief by a board that the college can grow out of fiscal problems is a commonly held axiom. However, it assumes that they are not competing with any other colleges for more students.

“The college could do a better job of price discounting which will lead to more students enrolling.”

The problem is that the tuition discounts are simply a recognition by a college that its current price is out of equilibrium with supply (college’s need to enroll new students) and demand (student willingness to enroll). Also, these discounts are coming at a time when many colleges are finding that their potential student pool is shrinking. So simply setting higher enrollment goals and offering larger tuition discounts does not guarantee more students will enroll.

As part of the interview, you might suggest that maybe the college could combine both an enrollment increase and expense cutting as a turn-around strategy. However, you may then hear that expense cutting strategies can be stymied by the faculty because (the board) granted the faculty the authority to approve all expenditures.

In other words, an interview at a college looking for a turn-around strategy does not necessarily mean that it is ready for the angst of developing and implementing said turn-around strategy.

Presidential Candidates at Turn-Around Colleges Need This Information for the Interview:

-

- Conflicts, culture, and relations within the institution, including with its alumni and with key external constituencies

- Financial condition – audits

- Status of accreditation

- Law suits

- Relationship with banks

- Position of the local press regarding the institution

Before the Employment Contract Is Signed, the Candidate Should Have This Understanding with the Board:

- Explicit acknowledgement that the Board understands and accepts the implications of strategies posed by the president during contract negotiations.

- The contingency plans in response to any known fall-out from decisions.

- The willingness of the Board, its chair, and executive committee to publicly meet with constituencies and state their support for the President as strategies are being implemented.

- What happens if the board chooses to meet with the faculty or other critical constituencies without the president and if those meetings have the potential of undermining the president.

- An explanation of what happens if a board member expresses to key constituencies lack of support for board approved strategies and plans.

- The conditions under which the president would leave the institution beyond the normal moral turpitude, incompetence, or insubordination.

by Michael K. Townsley | May 21, 2022 | Strategic Planning

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

Several years ago, higher education leaders expected to see a nice bump in the size of the student pool between 2021 and 2024. However, recent data indicates that enrollments are continuing to decline following the drop in numbers during the COVID pandemic in 2020. In 2019, Nathan Grawe wrote that the financial crisis of 2008 led to fewer births in that year, which would impact the 2026 student market.[1] (This outcome is apparent in Chart I later in the discussion.) Grawe also stated that declining enrollments in the eight years prior to 2018 was:

“… the result of a demographic plateau. Surely the current downward trend largely reflects recovery from the deepest recession in modern economic history. Even as we contemplate new demographic trends, we should not lose sight of the many ways in which economic forces drive a range of educational outcomes, including enrollment, the desire for credentialing, and trends in students’ choices of academic majors.” [2]

It appears that as new students consider the choice between enrolling in college or other options, fewer are choosing college at all, be it a 2- or 4-year school. The shift in the choice decision may be attributed to the cost of debt, the low-payoff for some majors, government incentives to the work force to remain unemployed, or other not yet unplumbed reasons.

As disruptive as dwindling student markets are toward college budget, so also is the rise in the cost of skilled and unskilled labor due to tight labor markets. As will be considered at the end of this discussion, the confluence of falling enrollments and tight labor markets could have a profoundly negative effect on the financial viability of many private colleges.

Births and Tuition Net Revenue

The Covid 19 pandemic had the potential of pushing a number of private colleges to the brink of survival. However, most were saved by large cash grants from the federal government. Yet, college leaders recognized that the pandemic would soon be followed by a demographic crash in the student market resulting from a sharp decline in births starting in 2000, tempered by a recovery in births in 2006, followed by another decline that lasted until 2010.

Chart 1

Change in the Number of Births between 2000 and 2020[3]

If the declining births in the early part of this century are pushed forward eighteen years to the traditional college entry age, the effect of the decline on enrollments can be more readily discerned. The first big decline in 2019 would be followed by a recovery through 2021 with a further decline from 2022 and 2023, and then a strong recovery in 2024 followed by a precipitous decline lasting until 2028.

Unfortunately for colleges, the first recovery year from the increase in 2003 births expected to occur in 2021 was quashed by the pandemic. Most colleges were able to absorb the unexpected enrollment decline and concomitant loss of student revenue through large federal grants.

Table 1 indicates that although enrollment declined in 2020, it should not have been unexpected given the decline in births in 2002. If we return to Chart I, the data suggests, given the increase in births in 2003 that 2021, we should see a strong recovery in student enrollment. However, either the pandemic or other forces cut the expected recovery short at most private, not-for-profit institutions. The exception in 2021 was enrollment of female and male students at highly selective private institutions, where enrollment increased. Table I contains some very worrisome news for less selective private colleges because they generally reported further deterioration in enrollment. In addition, less selective institutions must also be concerned that the momentum provide by female enrollment to offset long-term waning of male enrollment is slipping away. If the growth in enrolling women is slacking off, then many less selective private colleges could be in deep financial trouble.

Table 1

Private Not-for-Profit Colleges; Changes in Enrollment by Selectivity and by Gender [5]

| |

Highly Selective

|

Very Competitive

|

Competitive

|

Less Selective

|

|

Male

|

|

|

|

|

|

2020

|

-3.3%

|

-2.2%

|

-3.2%

|

-1.9%

|

|

2021

|

4.3%

|

-0.3%

|

-4.4%

|

-2.8%

|

|

Female

|

|

|

|

|

|

2020

|

-2.6%

|

-0.5%

|

-3.4%

|

-2.3%

|

|

2021

|

5.5%

|

-0.8%

|

-5.2%

|

-4.0%

|

|

Total

|

|

|

|

|

|

2020

|

-2.8%

|

-1.2%

|

-3.2%

|

-2.1%

|

|

2021

|

5.2%

|

-0.5%

|

-5.6%

|

-3.3%

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Colleges must now hope that the big recovery in births in 2005 and 2006 will lead to a strong increase in enrollments in 2023 and 2024. If enrollments do surge in that period, colleges may be granted a brief two-year period to rebuild financial resources and implement new strategies. If enrollment does not improve during this period, then private (especially resource poor private) colleges, may find that their financial condition is beyond repair. Even if enrollment does expand between 2023 and 2024, the steep fall in the new student market by 2028 (see Chart I) does not bode well for resource poor, less-selective colleges. Less optimistic population data might even indicate that higher education will be struck by another collapse in the student market between 2034 and 2038. When the next major decline occurs in ten years, no one can reliably predict the impact of new technology in substituting classrooms with visual-reality or of corporations taking over large chunks of educating prospective employees because college graduates lack significant work-related skills that they had brought to the workplace in the past.

In several important ways, the decision to go to college may no longer be mainly influenced by parents. In prior decades, the decision to enroll in college was mainly influenced by the income and educational level of parents.[6] There seems to be accumulating evidence that enrolling in college and in a particular academic program is becoming more dependent on financial outcomes. In other words, uncertainty in the predictability and scale of enrollments will not diminish in time.

As a sidenote, the effect on college enrollments from the massive influx in new immigrants in the recent past is not known and may not become evident for several years as they and their children become more fully assimilated into society and the economy.

Labor and Cost in Higher Education

Labor and the cost of labor has always been a major issue in college operations. The problem of labor cost is not new, as we can recall that cost-of-living adjustments (COLA) were a common aspect of salaries and payrates during the high inflationary period that ran from the early 1970s to the early 1980s. This period of inflation was called stagflation because inflation was high and economic growth was low. Chart II has two inflections in 2006 and 2020, the first inflection represents the high point in real estate construction leading to a debt crisis and economic crash. The second inflection is a small decline that preceded a massive decline in the labor force and the labor participation rate. Hiring has become problematic because the labor force and the participation rate fell dramatically and do not show the resilience to support the economic recovery after the worst of the COVID pandemic.

Chart II

Percentage Change in the Size of the Labor Force and the Labor Participation Rate

There is a question in today’s labor market as to why immigration has not stimulated a larger labor force and larger participation rates. This puzzle may be due to how the government defines and counts labor and labor participants. For a higher regulated organization like a college, they may not be able to satisfy immigrations regulations and to use the massive influx of new immigrants for their data.

The New York Post included an explanation of the decline in the labor force and participation rate for the last year based on data that was available in December of 2021. The main points of this article are:

- “There are some 3.6 million fewer workers than there were in February 2020. By some measures, the number is much higher and could be 6 million, according to Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandy.”[7]

- “The majority of the missing workforce are people 55 and older – some 2.4 million people – who either retired early by choice because they could financially or low-income retirement-age workers who were axed at the start of the outbreak. COVID-19 nearly doubled the retirement rate for 2020, fueling the largest exit of older workers from the workforce in at least 50 years.”[8]

- “There’s also the simple, tragic fact that the pandemic has claimed 800,000 lives — and about half a million of those victims were working-age adults.”[9]

- “The rest of the missing workforce is a combination of people in two-salary families who decided to make due with one income; those who’ve decided to start their own business or take “gig” employment; and discouraged workers with low incomes.[10]

- “The US Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey also noted on Wednesday that about 4.9 million said they were not working because they were taking care of children who were not in school or day care (Some of these people show up on the unemployment numbers because they are still looking for work.)”

These are massive losses to the labor market that will not be easily made-up by immigrants, especially during a period when the effects of falling birth rates are hitting the labor market.

What Does Student and Labor Market Shortages Mean to Higher Education?

The confluence of student and labor market shortages will bring considerable pain to many private colleges and universities. First, price competition will accelerate as colleges try to attract students from a small market. Typically, price competition in higher education takes the form of tuition discounts. According to the annual tuition discount report by the National Association of College and University Business Officials, the average tuition discount for new students in 2020/21was 53.9%.[11] A tuition discount of 53.9% means that a college only receives about forty-six cents in cash on the dollar. There is even evidence that some private colleges are discounting tuition for middle-income students between 62% and79%.[12] Those colleges are only receiving from their middle-income students between thirty-eight cents and twenty-one cents on the dollar. It is hard to fathom how these colleges will be able to fund operations at these high discount rates. If more colleges move to these out-sized tuition discounts, many private colleges are going to be pressed to the wall. Speaking to this last point about ever higher tuition discounts, NACUBO, in a 2020 survey of business officers, found that 80% believed that COVID would have a continuing effect on tuition discounting.[13] Given the steep drop in the size of the student market, the combination of COVID and shrinking student markets will drive out the cash needed to support operational expenses.

In the case of labor rates, as labor markets shrink and organizations seek to hire more employees, the common economic response will be to either raise pay rates or replace employees with capital equipment. Higher education does not have the technology to replace employees. Also, accreditation rules usually limit reductions-in-force in professional positions. Plus, the administrative information technology systems are expensive and are not designed to replace staff. However, data is not currently available for private colleges to determine if a shrinking labor market is leading to higher labor rates. Nonetheless, it would not be surprising that colleges are going to have to increase their payroll if they want to keep their employees or hire new employees.

Summary: the Confluence Crunch

Chart III

Confluence of Changes in Births, Labor Force and Labor Participation Rate from 2000 to 2020 in Five-Year Increments[14], [15]

Chart III illustrates how birth rates, the labor force, and labor force participation rates have moved in lockstep between 2015 and 2020. Even though the chart does not include 2021 data, it is hard to imagine that the picture improved in the middle of the COVID pandemic.

Contracting student and labor markets could well produce a crunch as cash lost from higher tuition discounts will not be able to cover the demand for rising labor pay rates. If private colleges cannot resolve this conundrum, many of them will fall by the wayside and be forced to close, leaving only memories to alumnae/alumni and former employees.

References

-

Grawe, Nathan D. (November 1, 2019); “The Enrollment Crash Goes Deeper Than Demographics” The Chronicle of Higher Education; The Enrollment Crash Goes Deeper Than Demographics (chronicle.com). ↑

-

Grawe, Nathan D. (November 1, 2019); “The Enrollment Crash Goes Deeper Than Demographics” The Chronicle of Higher Education; The Enrollment Crash Goes Deeper Than Demographics (chronicle.com). ↑

-

“United Nations – World Population Prospects” (Retrieved December 23, 2021); United Nations – World Population Prospects; Births – USA Facts; www.macrotrends.net. ↑

-

“National Student Clearinghouse Research Center’s Regular Updates on Higher Education Enrollment 18-Nov-21” (Retrieved December 21, 2021); COVID-19: Stay Informed – National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (nscresearchcenter.org). ↑

-

Zemsky, Robert and Penney Oedel (1983); The Structure of College Choice; College Entrance Examination Board; New York. ↑

-

Fickenscher, Lisa (December 17, 2021); “COVID’S Labor Market Shakeup: this is where the missing 3.6 missing workers went”; New York Post; How COVID shook up the labor market (nypost.com). ↑

-

Fickenscher, Lisa (December 17, 2021); “COVID’S Labor Market Shakeup: this is where the missing 3.6 missing workers went”; New York Post; How COVID shook up the labor market (nypost.com). ↑

-

Fickenscher, Lisa (December 17, 2021); “COVID’S Labor Market Shakeup: this is where the missing 3.6 missing workers went”; New York Post; How COVID shook up the labor market (nypost.com). ↑

-

Fickenscher, Lisa (December 17, 2021); “COVID’S Labor Market Shakeup: this is where the missing 3.6 missing workers went”; New York Post; How COVID shook up the labor market (nypost.com). ↑

-

Whitford, Emma (May 20, 2021); “Tuition Discount Rates Reach New High”; Inside Higher Education; Tuition discount rates continue to rise while enrollment stagnates, report shows (insidehighered.com). ↑

-

“Which Private Colleges Offer the Largest Tuition Discounts to Middle-Income Families?”; (Retrieved: December 27, 2021); Edmit; ttps://www.edmit.me/blog/which-private-colleges-offer-the-largest-tuition-discounts-to-middle-income-families. ↑

-

McCreary, Katy (May 19, 2021); “Private College Tuition Discounting Continued Upward Trend During COVID-19 Pandemic” National Association of College and University Business Officials; Washington, DC; Private College Tuition Discounting Continued Upward Trend During COVID-19 Pandemic (nacubo.org). ↑

-

“United Nations – World Population Prospects” (Retrieved December 23, 2021); United Nations – World Population Prospects; Births – USA Facts; www.macrotrends.net. ↑

-

“Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: Years 1999 to 2021” (Retrieved December 20, 2021); Employment Projections program, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; Table 3.1. Civilian labor force, by age, sex, race, and ethnicity, 2000, 2010, 2020, and projected 2030. ↑

by Michael K. Townsley | May 21, 2022 | Strategic Planning

Small independent colleges may require planning of a different kind.

If you think about it, the literature of educational planning is in some ways bizarre.

Much of the literature assumes that colleges and universities are reasonably well financed, that the administrators are interested in high-quality learning and better management, and that decision making is fairly rational. Planning models assume replicable behavior and offer strategic planning processes that urge leisurely, logical sequences.

Sometimes educational planning actually occurs as scholars suggest. But many colleges live by their wits, battling bankruptcy, improvising, and groping in the darkness. Most persons in a college are only remotely aware of their institution’s true financial state and are oblivious of the financial consequences of many of their initiatives.

The behavior of college and faculty leaders is occasionally farsighted, astute, and wise. But more often it resembles the be-

Michael Townsley is vice president for finance at Delaware’s Wilmington College. A graduate of Purdue University, he has served as a business manager in Indiana and holds a master’s degree from the University of Delaware.

havior of Tolstoy’s officers in War and Peace, grappling in the confusion and blood of battle, or the ideological, posturing behavior that Simon Schama brilliantly depicts as the reality of the French Revolution in his recent book, Citizens.

These behaviors are especially true of the 500 to 600 smaller private colleges in the United States that live precariously on the brink of bankruptcy. This fact was first noticed by William Jeilema1 in 1971, and it seems just as true today. It is not sufficiently realized that approximately one-sixth of America’s 3,400 institutions of higher education live in constant financial trouble. According to the U.S. Department of Education records, nearly 43 percent of all private colleges depend on students for more than 75 percent of their revenue.2 For nearly all these institutions, orderly higher education planning is a distant yearning. For them, planning, such as it is, is usually geared to short-term financial crises and enrollment shortfalls.

To illustrate, here is the true story of one such college, which I will call Camus College. It is an effort to describe college management and planning as they actually take place at many institutions in the less affluent sixth of U.S. higher education.

Camus College was founded in 1968. In its first fifteen years the college reported deficits in all but five years. In three of the five years in the black, emergency gifts from benefactors kept the college from closing its doors.

Planning the origin of the college

Camus College began as a spark in the mind of a brash, highly ambitious, young student-affairs dean at a college in New York State. In the mid-1960s he had conceived the idea of a new college to serve late bloomers, underachievers, and students in need of a second chance. The early success of Iowa’s Parsons College was probably a strong influence. His keen desire to be a college president was also a driving factor. A cagey visionary, he also noticed that the Vietnam War had prompted young men to attend college in great numbers and that federal aid to students had begun shooting upward in

1964—65.

He looked for a campus for his college in several eastern states. Then,. near a medium-sized city, he discovered an abandoned motel, comprising a once-handsome lodge and four derelict but large, separate housing units. The motel once had a busy road running in front, but the road was now relatively quiet because a new expressway had been constructed a few miles away. This dean of students took his savings account, borrowed

Most persons are only remotely aware of their institution’s true financial state.

from several relatives, and offered $10,000 for the deserted motel. The bid was accepted, and Camus College was born.

The youthful president then recruited several hundred students from surrounding states and provided a residential, student-oriented experience, taught in the old lodge by underpaid instructors within a limited cur-

riculum, which focused on the liberal arts. Since the college was without endowment, the president tried to run it as a business. Unfortunately, he never made ends meet. When enrollments declined in the mid1970s, after the Vietnam War ended, Camus College seemed ready to close its doors, especially since the former motel buildings needed substantial capital repairs and renovations. The enterpreneur-president then moved to another college.

Planning for survival

To keep the colleges classrooms open, the next president scrambled to find additional students—fast. To do so, the college rapidly turned away from being a small, caring, residential college for underprepared students from surrounding states to becoming a commuter college for older, employed, minority, and part-time students who lived nearby. The college also sought and obtained a U.S. Department of Defense contract to teach military personnel at a nearby military base. This “strategy,” hastily devised to meet urgent necessities, radically transformed the institution.

To further boost enrollments, the college’s leaders designed a totally different kind of college. Instead of a liberal arts curriculum, the college mainly taught practical, career-oriented, and even a few vocational courses, concentrating on business, communications, and behavioral studies. Camus also arranged to teach the second two years of college at a community college in the area and aggressively sought other two-year college graduates.

Instead of the protracted semester calendar, Camus College switched to eight-week semesters and offered intensive one-month courses that met on four consecutive weekends. To help attract students, the college adopted a strategy of maintaining the lowest private college tuition in the state, advertising this advantage. And to head off financial collapse, Camus College cut its administrative staff to the bone and moved away from mostly full-time faculty-the highest cost item at any college — to a largely

part-time, adjunct faculty. The use of adjunct faculty reduced the expenses of teaching a course by 40 to 50 percent.

Last, Camus College officials solicited private gifts, especially from its board of trustees. For the early 1980s, the college needed at least $250,000 a year in benefactor gifts to balance the books.

The new “plan” worked well, ostensibly. Head count enrollment in the early 1980s increased at an annual rate of 13 percent. Camus College enrollment shot up from a few hundred students in the mid-1970s to roughly 1,000 students in the early 1980s. Then in 1981, Camus received a $450,000 gift for a renovation. The new strategy for Camus seemed to be working.

Planning for recovery

In 1981, however, Camus College ran out of money. There was a cash flow crisis. The auditors hinted that the college was broke. But how could this be? It turned out that while the college’s aademic leaders were constructing their concrete new strategy, the financial structure supporting the concrete was made of wood saplings.

The crisis was the culmination of a failed effort during the previous spring to reduce the substantial deficit to a manageable size. When the audit arrived that fall, it showed a small deficit of $21,000 and emergency gifts of only $42,000. What was not readily apparent was that, to keep the deficit in control, operating expenses were being met by transferring funds from the renovation project. These transfers absorbed nearly 50 percent of the renovation gift. However, the project still had $450,000 in bills to be paid. There were no other cash reserves in the college. Much of the balance of the gift quickly disappeared that fall. Like the previous spring, it was used to cover payroll and other bills. Nothing was available to pay for the renovations when those bills arrived in late October.

These problems were compounded by a personnel problem in the business office, typical at small, poor colleges, which often

do not realize that institutions at the financial brink need additional expertise in the business office. At poorer institutions, financial planning is at least as important as

At poorer institutions, financial planning is at least as important as

educational planning.

educational planning. Instead, these colleges frequently hire bookkeepers, unsuccessful-in-business accountants, or someone who is said to be “good with money.”

For several years the college’s auditors had urged the president to improve operations and personnel in the business office. She knew she should do so. Two years be-fore the 1981 cash crisis, the president had asked the business manager for a precise statement of the college’s cash needs so that she could ask one benefactor for a gift large enough to put Camus on a solid financial foundation. The business manager came to the president’s home with boxes of check stubs, cancelled checks, and cash records, saying he had given up trying to reconcile the checking accounts and confessing he had no way of coming up with an estimate of the cash requirements of Camus College.

She decided to ask for a gift of $400,000 and received a very large contribution. But within ten months the college reported an-other deficit. Finally, she asked the business manager to leave and hired an experienced business officer, who, after several days on the job, was aghast.

He had learned that the office did not post its ledgers, so there were no regular financial statements, no budget reports. Students were not billed for tuition and expenses systematically, sometimes not at all. Purchases were rarely authorized by a purchase order. Bills were stuffed in drawers until money was available. NDSL accounts were not billed. Contracts for the adjunct faculty, which represented 80 percent of the

classes offered at the college, were inaccurate or unavailable; and the costs of paying adjunct teachers had been underestimated by one-third for several previous years.

Aided by a new accountant and the auditors, who were called in to set up the books, the new business officer speedily set up a new financial system. Suddenly payday arrived. The payroll was $45,000, but the college had only $15,000 in its checking accounts. Frantic, the new business manager called the old business manager, who advised his replacement, lust take the money from the remainder of the $450,000 gift the college received in 1981 for renovations.” He said that’s what he had done several times in the past.

Was the short-term cash shortage in fact a long-term cash shortage? The business officer decided to work up a forecast. To his horror, he found that Camus College would need $600,000 within four months to keep its payables current, pay back the money taken from the renovation project, and have a two-payroll cash cushion.

He took the forecast to the president, who was shocked. Screwing up her courage, she asked the chief benefactor to donate $600,000. He did, reluctantly, but in two payments. The second payment was conditional upon the college having in place a full financial-reporting system in six months. Through a fierce effort by the business staff, Camus College was soon able to provide the president, chief benefactor, and board of trustees with frequent and regular computerized reports on the financial condition of the college for the first time in its history. The chief benefactor was so impressed that a year later he gave the college $3.5 million to begin an endowment fund.

Planning for continued solvency

The mess in the business office allowed many in the college, especially the faculty, to think that the college’s financial problems were only a matter of the disheveled business office. They continued to overlook the precarious financial condition of the college. Even with the business office’s new-found

competence, Camus continues to have serious financial problems.

The switch to a commuter college meant nearly empty residence halls and a bookstore that loses money. More than 88 percent of the latest budgets are based on student revenues, and the local market is no longer growing. Faculty continue to push for the college to replace its adjunct faculty with more full-time teachers. (The cost of hiring one full-time faculty person is almost two and one-hall times that of hiring adjunct instructors to teach the same courses.) The faculty make these demands partially because of the criticism from the regional accrediting group and from others who prefer full-time faculty.

A number of the full-time faculty at Camus sincerely believe that a return to a traditional liberal arts program would secure the school’s reputation. This demand is made despite the evidence that the college does not have the resources to support a traditional program, nor does it have access to that portion of the student market.

Other factors at Camus contribute to its financial condition. Every year Camus makes such a large draw from its small endowment that the fund is unable to keep pace with inflation. And until his resignation a few years ago, the college had a vice president for academic affairs who refused to give up his prerogative for spending funds without regard for budget limits or normal financial and accounting procedures.

The college appears to have an urgent need for a new academic strategy and financial plan. But none is forthcoming. Camus views itself as moderately healthy. Some contend it is growing stronger because head-count enrollments since 1981 have been increasing. An unexpected gift in 1983 provided endowment income that along with large tuition increases has adequately covered the gap between revenue and expenses. As a result, the college has not reported a deficit in seven years. In fact, its finances are strong enough to support major renovations to a section of the old motel, while the rest of the motel has been replaced with a new building.

Living day-to-day

The college continues to practice brinkmanship. Strategic planning is outside its purview. As it has done since its inception, Camus operates largely by the seat of its pants. The radical shift in the 1970s to serve older, nontraditional students was a desperate, fortuitous shift in the face of possible closure. To call this shift a strategy is to give it a meaning that is undeserved.

Camus’ real strategy is to respond to what the market gives the college. Strategy implies that forethought is given to consequences of a decision; yet consequences at Camus are often not contemplated until after the fact. So if a new curriculum was installed,

The college’s real strategy is to respond to what the market gives.

it was put in place after the market demanded it. Consideration of its impact was largely ignored.

If strategic planning is at the minimum a marshalling of resources to prepare an institution for the future, then Camus is not a stellar example. Data on its student body, its student market, or its competitors are not applied to the analysis. Planning is based solely on an intuitive sense of the forces affecting the college. Since the college responds to change intuitively, it is unable to respond beforehand to the need to make a strategic change. Camus acts only when evidence indicates that there is no alternative but change. This situation is well understood by the president, who has tried to make it evident to others in the college.

Camus’ lack of interest in strategic planning may be caused by its own limitations. The college has very little in the way of resources to devote to planning. All of its expenses go toward its mission, providing working adults and minorities with a college education. Except for the president, the vice president for academic affairs, and the business manager, everyone else is a technical administrator. There is little time available for planning. One consequence is that financial planning is not coupled with academic planning. The likely financial consequences of innovations —new academic programs, faculty promotions, or new kinds of students—are seldom costed out in advance. And often, close tracking of the revenues and costs of novel changes is not done.