First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

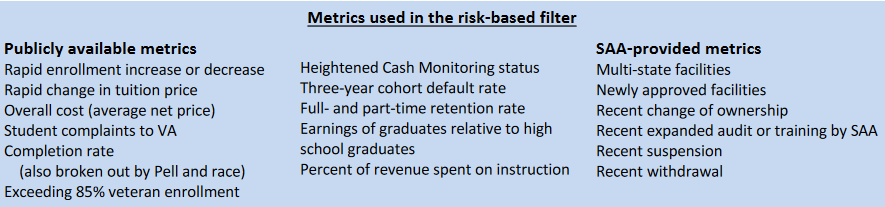

The February 2, 2022 issue of Inside Higher Education carried the article “Using College Outcomes to Gauge Risk for Students” by Doug Lederman. [1] The article addressed how to protect veterans from choosing a college that might not survive. The article reviews several measures to identify the potential signs that a college might fail. This blog will comment on assumptions of the underlying measures of college survival and the validity and construct of those measures. The article includes these “metrics used in the risk-based filter.”

The article does point out a fundamental political question raised by Rebecca S. Natow, Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy at Hofstra University:

“She said via email that an accountability regimen that applied to all colleges and universities …would struggle to gain the sort of bipartisan support that measures about veterans do.

The two main political parties have been much less likely to agree on accountability policies affecting Title IV programs more broadly, such as the gainful-employment rule, Natow said. It could be brought about through executive action, as much federal policy making in higher education has been [recently], but that typically results in legal challenges and flip-flopping as a new administration takes office.

Leaving matters in the states’ hands, in contrast, typically results in vastly uneven regulation, with some states being rigorous and others less so, Natow said.”

Moreover, another broad assumption is that government bureaucrats would enforce regulations to constrain risk. Instead, bureaucrats might determine that the greater risk is to themselves because enforcement could see the demise of institutions that are supported by powerful interest groups and by formidable political leaders. One example of this phenomenon of non-enforcement of risk regulations is that year after year the same colleges fail the Department of Education (DOE) ‘Financial Responsibility Test,’ yet the DOE rarely takes action.

General Comments: This section covers several significant sources of inefficiency.

- Managing risk in higher education assumes that colleges are attuned to factors that increase risk and that they have the power to control them.

- An important problem with nearly every metric and model of risk is that they are not rigorously tested to evaluate if they are valid. Too often the models are victims of post hoc analysis because they don’t take into account colleges that have closed.

- Of course, the main question regarding risk is how to define risk in higher education. Richard Cyert provides a way into understanding that risk. According to Cyert, a college needs to reach a state of economic equilibrium to assure its long-term survival. According to his model, financial equilibrium occurs when there are sufficient resources to sustain an institution’s mission for current and future students.[2] Therefore, risk would be the probability that the financial resources of an institution could or could not sustain the academic program (assuming that academic programs are the primary mission of the institution) for current or future students.

Comments about Risk Metrics and Models:

- Risk metrics are burdened by the inherent problems associated with the excessive aggregation of institutional data that limits the capacity to clearly identify issues below the broadest institutional levels. In other words, because refined data is not available, models and metrics too often assume that available and overly aggregated data will be valid predictors of risk.

- Over the past several decades, financial risk has been measured by importing business ratios. The assumption is that business ratios can capture the financial condition of an institution of higher education. However, business rates are designed to measure risk in terms of the capacity of the enterprise to generate sufficient cash flow to sustain on-going operations. Colleges, on the other hand, can and often survive for decades on the cusp of financial disaster as measured by business ratios because annual gifts, new government funds, or donors who make large gifts repeatedly pull an institution’s chestnuts out of the fire.

- Even though some colleges have survived for years as mere husks of an institution of higher education, these institutions often fail to achieve Cyert’s equilibrium condition that colleges need sufficient resources to support their mission and to serve their students for the short- and long-term. When colleges are merely husks, they too often may produce a degree with little or no value to graduating students.

- Certain risk-filter models hypothesize that they can forecast grave risks using seven or more years of long-term data for predictor variables. The problem with these models is it they assume that the predictor variable is continuously downward sloping. While these models may identify some institutions at risk, they often miss many institutions where early data may be positive, and then due to external or internal conditions, the predictor data suddenly turns negative. Regrettably, the adverse effect of a short-term and hazardous decline in a predictor variable may be dampened by earlier positive performance using long-term data. The best way of testing a risk-filter model is to test it against a data set that includes institutions that have already failed. Sadly, this data is often hard to locate because when institutions close, they are no longer identified in data sets.

Risk Based Filter Metrics Included in “Using College Outcomes to Gauge Risk for Students”

The following table is from the Inside Higher Education article, which includes risk metrics that were being considered by the Veterans Affairs Administration to protect veterans from enrolling in a failing college. These metrics are also commonly found in other risk models. After the table, there are several comments about the Veteran Affairs metrics suggesting which metrics are the most and least valuable.

The following risk-based factors are of modest or no value in determining short-term risk:

- Rapid enrollment increases or decreases: This metric is used in risk models and financial reviews, because for most private colleges and universities enrollments are the main drivers of revenue. If the period to measure the change in enrollment is too long, the change within the period may mask real problems in a shorter time frame. Change in enrollment is a worthwhile metric only when compared to changes in direct expenses (instruction, student services, and academic support).

- Rapid change in tuition price: this measure is an insufficient measure of risk because it does not get at the price paid by a student. The metric Overall Cost does measure the cost to a student.

- Completion rate (by Pell and race): This is a pertinent measure for government agencies to determine if their investment in a college is producing value for veterans. Moreover, prospective students may choose not to enroll at an institution with high attrition and low graduate rates. This measure is not a valuable risk metric of short terms risk because it requires data collected over a long period of time.

- Exceeding 85% VA enrollment: This metric is a VA regulatory measure to limit funding to an institution that mainly focuses on veterans, but it does not measure risk of institutional failure.

- Three-year cohort default rate: The presumed default rate is on federal loans. The underlying assumption is whether prospective students will continue to enroll if they graduate with loan balances that cannot be paid from their income. This metric might be useful in the long-term assuming that prospective students take earning after graduation into account when they agree to loans. However, the effect of the three-year cohort metric may become evident only after the college or university is already about to close due to other factors.

- Earnings of students relative to high school graduates: This metric is both an institutional and an academic program issue. The question is: “What is the point of enrolling in a program if a degree has no more (or even less) value than a high school diploma?” This issue is also germane to institutional marketing efforts. Assuming that future earnings from an institution or a program are known to prospective students, many will reject the choice if future earnings are insufficient to cover future expenses, as was noted in the default rate comment. This metric would be useful in analyzing programs in a long-term analysis, but it may have little practical value as a measure of short-term institutional risk unless all or most of the institution’s programs have little relative economic return in comparison.

- Percent of revenue spent on instruction: The assumption here is that as the percentage of money for instruction decreases, the quality of instruction also decreases. However, innovations in instructional delivery can reduce costs and increase quality. Instructional expenses can decrease at colleges that allocate more funds for student services and academic support to improve retention and graduation rates. ‘Percent of revenue spent on instruction’ as a risk metric is too limited.

- Note that the SAA metrics are mainly of interest to accreditors or government agencies and are not discussed here.

The following risk-based factors are of effective value in determining short-term risk:

- Overall Cost (average net price): This metric represents the out-of-pocket costs that veterans are being charged. If the metrics in the table are intended to measure risk, then this metric can illuminate the cash flowing from enrollment to cover direct costs. Multi-year evidence shows that while tuition net of institutional grants has fallen (in other words, students are paying less out of pocket), direct costs have been increasing. This means that the risk to the institution is increasing as net tuition declines and direct costs go up.

- Student complaints to VA: This is a good way for the VA to identify problems because the complaints are coming directly from students enrolled in a college or university.

- Heightened cash monitoring status: This metric gets at the central issue of whether an institution can survive. If a college or university does not have sufficient cash reserves to cover on-going operations and debt-service, then they may have to turn to lenders for short-term loans. If short-term loans increase in size over time, then the institution is at risk when unexpected events like the Covid pandemic occurs.

- Full and part-time retention rates: As retention rates fall, the need to find new students to bolster enrollment, along with associated marketing costs, increases. In addition, there is a possibility that falling retention rates imply that the academic programs are not designed to reach the academic skills of the students enrolled by the college. This metric also ties into the discussion about ‘Completion Rates’.

Several Other Metrics That Measure Risk Effectively:

Here are several risk metrics that could be used independently or assembled into a model:

- Net Student Revenue: If the sum of tuition net of institutional grants plus auxiliary income (excluding hospitals) and net of expenses is increasing, Net Student Revenue yields more funds for operations, while shrinking Net Student Revenue reduces capacity to support operations, which places the institution at risk.

- Net Student Revenue to Direct Expenses (instruction, student services, and academic support) Ratio: An increasing Net Student to Direct Expense Ratio is able to support a greater proportion of direct expenses or even produce excess revenue to cover indirect costs (ex. institutional support, plant, debt, etc.). A decreasing ratio reduces the proportion of funds available for direct funds and puts pressure on the college to find other sources of revenue, which is often not possible for tuition dependent colleges, thus placing the institution at risk.

- Class Size Ratio (the average number of students in front of an instructor): The larger the class size the greater the net direct instructional revenue and the smaller the class size the lower the net direct instructional revenue, increasing institutional risk.

- Class size in classes required by a major: Very small class sizes indicate that the major is not supporting the operational costs associated with the major. The greater the number of these underutilized majors, the greater the institutional risk.

- Net Tuition Revenue plus grants to Operational Costs of a Major Ratio: A small or declining ratio suggests that the major is unable to support itself. The more the number of these majors, the greater the institutional risk.

- Space Usage Ratio: This ratio measures the percentage of building space used during a fully employed period of sixteen hours. A low usage ratio suggests that building space is not fully optimized to cover debt service, operational costs, or repair and maintenance, and is an indicator of future risk.

- Cash Flow Metrics: As indicated in the preceding section under the heading “Heightened cash monitoring status,” cash is a common metric in measuring risk. Here are several ways to measure if the college is building or depleting its cash reserves:

- Cash Flow from Operations: This metric is found in audit reports and shows cash is the main reserve from which operations are supported.

- Cash from Operations to Net Change in Assets from Current Operations: This measures whether operations are increasing or depleting cash.

- Total Cash: This shows if the college is building its cash reserves from all sources of cash. It also measures if trends in total cash are increasing or decreasing.

- Negative cash trends are a definite indicator of future risk.

Risk Management – Preserving the Mission

If risk is defined by Cyert’s proposition that colleges risk their capacity to deliver on their mission if they do not have sufficient financial reserves, then the question arises: “How does an institution reduce its risk?” Colleges and universities can reduce risk by determining whether or not their mission is achievable given the resources that they have available. This proposition suggests that the following questions need to be addressed:

- What is the mission of the college?

- Does the mission fit the demands (expectations of students)?

- Does the mission need to be reconstrued to respond to the student market?

- If the mission needs to be rewritten, will the corporate by-laws support the change in the mission or do the by-laws need to be modified?

- Do academic programs need to be revised to respond to the expectations of students?

- Should resources, both fiscal assets and personnel, be reallocated in response to changes in the mission and academic programs?

- Ought the administrative footprint and physical assets be restructured or eliminated to release resources toward instruction and instructional support?

- What is the enrollment and net tuition price point needed to generate the funds needed to operate new academic programs and build financial reserves?

- How should marketing strategy and actions be redesigned to support changes in the mission, enrolled students, and academic programs?

There are many more questions that may need to be answered to perfect models of risk. Nevertheless, the economic environment reshaping higher education today makes it necessary to address these questions sooner rather than later.

ENDNOTES

-

Doug Lederman; (February 2, 2022) “Using College Outcomes to Gauge Risk for Students”; Inside Higher Education; A possible model for identifying riskiest colleges for students (insidehighered.com). ↑

-

Townsley, Michael (2014) Financial Strategy for Higher Education: A Field Guide for Presidents, CFOs, and Boards of Trustees; Lulu Press; Indianapolis, Indiana; p. 15. ↑