Pricing Power and Private Colleges and Universities

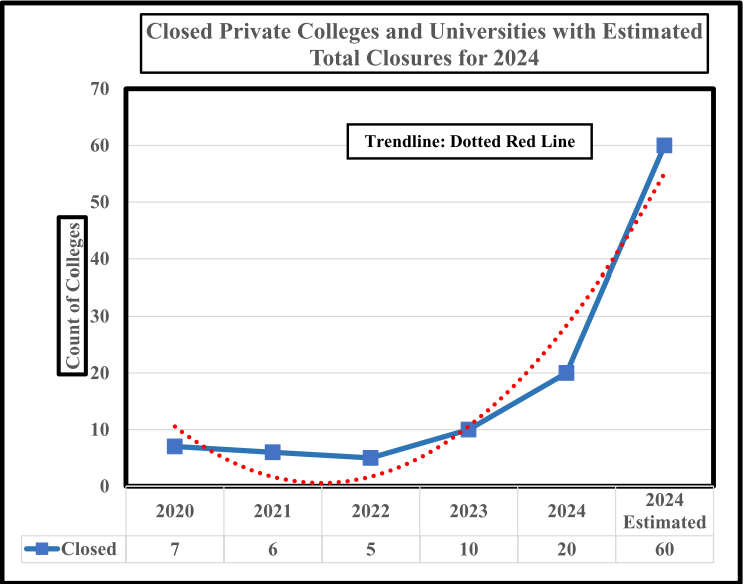

As of the first week of May 2024, Chart 1 shows that twenty private colleges have closed with a simple factorial estimating that sixty will close. The sharp exponential growth for 2024 does not bode well for many private colleges that are struggling to survive. Presidents and Boards of Trustees need to be cognizant of how tuition pricing decisions using ever-increasing tuition discounts to offset higher tuition prices can lead to contradictory or even unwanted effects on student decisions to enroll.

Chart 1

Current Financial State of Private Colleges and Universities

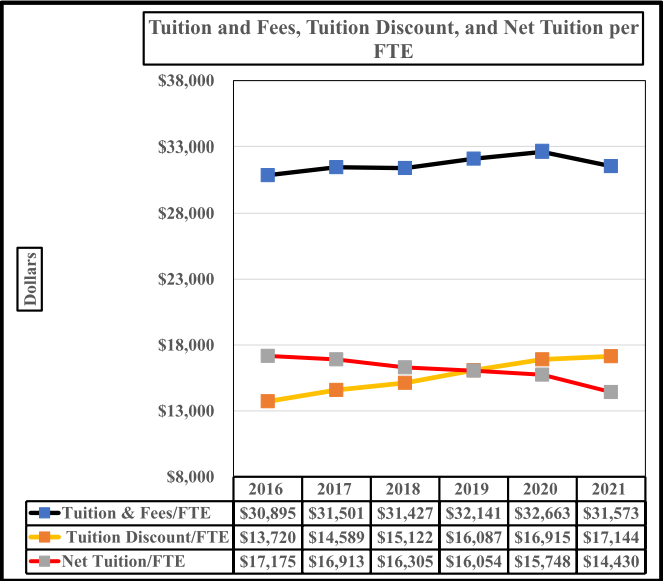

This paper now turns to what has happened with tuition pricing and the unintended consequences of those decisions over the past five years. Chart 1 and Table 1 adduce a major problem that has risen from tuition pricing decisions made by leaders of private colleges and universities. Chart 1

shows since 201: modest tuition and fee increases per FTE (full-time-equivalent student), an upward trend in average tuition discounts per FTE, and negative change in net tuition per FTE.

Dollars

Chart 1 indicates that the average net tuition per FTE crossed the average tuition discount in 2019, which suggests that from 2019 onward tuition discounts were exceeding the value of any changes in tuition and fees. If the past is a prelude to the future, more than likely tuition discounts will continue to increase after 2021. Because tuition discounts are unfunded by grants or endowment, they dot yield any cash benefit when they are increased. Unfortunately, tuition discounts diminish the amount of cash available to support on=going operational cash and force a college to draw cash from its unrestricted reserves.

Chart 2

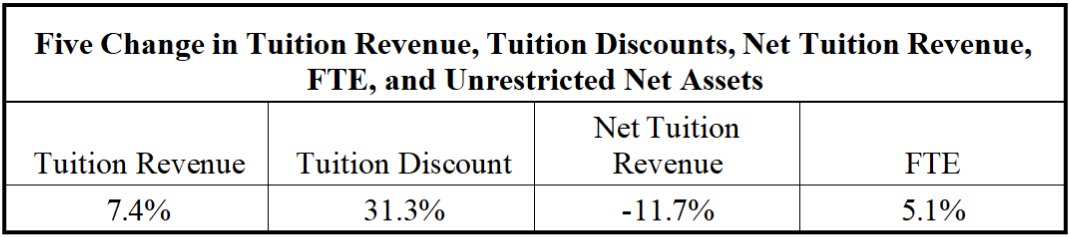

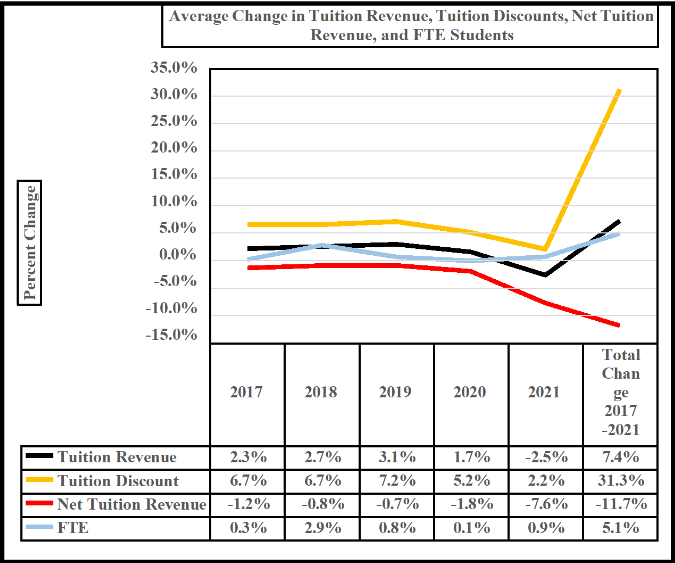

Table 1 shows the five-year change from 2017 to 2021 for tuition revenue, tuition discounts, net tuition revenue, and FTE enrollment. Although tuition discount was up 31.3%, FTE enrollment only grew 5.1%, while net tuition revenue fell 11.7%. Negative net tuition revenue means that there is less cash flowing from tuition revenue to support on-going operations. It is not unreasonable to conclude that these conditions contributed to an accelerated pace of private college closings. Based on closing data as of May 2024, the number of private colleges that closed was 100% higher than for calendar year 2023 and 150% greater than the average number of closings from 2020 to 2023.

Table 1

The failure of the tuition discount strategy to increase enrollment enough to offset lost revenue and cash has and will make it more difficult for presidents and boards of trustees to regain financial stability at many financially weak colleges. This paper uses basic economic theory to explain what shapes financial outcomes as colleges try to resolve their unstable financial conditions tuition and tuition discounts.

Conundrum of Tuition Pricing for Private Colleges and Universities

Before we start the discussion of tuition pricing, it would be useful to define several of the commonly used terms involved in tuition pricing and used to discuss tuition pricing decisions.

- Posted tuition and fees is the amount announced to the public for tuition and fee charges.

- Tuition and fee revenue is the amount of revenue received by the college from a student for tuition and fees; this figure is recorded in the accounting books and budget reports.

- Tuition discounts is an unfunded institutional grant that offsets a tuition and fee charge; these grants are recorded as expenses.

- Net price that the student pays after deducting institutional grants.

- Net price revenue is the net revenue recorded in the books that is paid by the student.

This paper uses basic micro-economic theory to explain tuition price setting. Theory posits that there is a price point where demand for a product or service and supply of that product or service are in balance. In balance means that at the price point the market for the good or service will be produced and purchased.

For private colleges and universities, demand is represented by a pool of students who file applications to one or more colleges. Supply comprises the colleges who offer enrollment in their majors to the student pool. Colleges competing for students are delineated by the choice set, which becomes evident when students file their applications. Therefore, the marketplace encompasses the student pool and their choice set of colleges. It is in this marketplace where the decision to enroll is at the intersection of the willingness of a student to accept and the price offered by a college.

Acceptance of an offer at a specific price is not necessarily at the tuition price advertised by the college. Typically, students and college agree on a net tuition price that is the amount the student owes after deducting a tuition discount. From the posted tuition. The discount is unfunded, that is, it is not supported by endowment funds. Since a tuition discount is unfunded, the college charges the discount to expenses and does not receive offsetting cash. However, a student may receive government grants or be awarded endowed scholarships that help a student pay for their net tuition balance.

Tuition pricing decisions is not simply a decision to accept a student at a given price, the college should take into account the price elasticity of the student pool, i.e.; student market. Price elasticity states that changes in price can have either a positive or negative effect on demand.

Elasticity generally operates as follows.

- If a market is elastic, price increases or decreases can have a significant effect on demand.

- If a market is inelastic, then price increases or decreases has little effect on demand, the demand.

- The price elasticity is: percentage change in quantity to the percentage change in price.

- If price elasticity is greater than 1, then price is elastic.

- If price elasticity is less than 1, then price is inelastic.

- If price elasticity is perfectly elastic; i.e.; a score of 0 or very near zero, then changes in price yield no changes in demand.

- Because elastic or inelastic markets can have a significant impact on the amount of product or service demanded, price elasticity can necessarily have an effect on revenue generated from sales.

Given the preceding statements on price elasticity and in the particular case of student demand, elasticity can have the following effects on tuition decisions:

- If the student market is elastic, then posted and net tuition increases or decreases can have a significant effect on the prospective student’s decision to enroll.

- If the student market is inelastic, then posted and net tuition increases or decreases has little effect on the prospective student’s decision to enroll.

- If the student market is perfectly elastic, then posted and net tuition, changes have little effect on the decision to enroll. (note reference for the preceding discussion can be found the Lumen Learning website).

Because price elasticity can have a positive, negative, or no effect on the decision to enroll, it follows that elasticity will directly affect tuition, net tuition revenue and the cash that flows from net tuition revenue.

Student Markets and Elasticity as of 2021

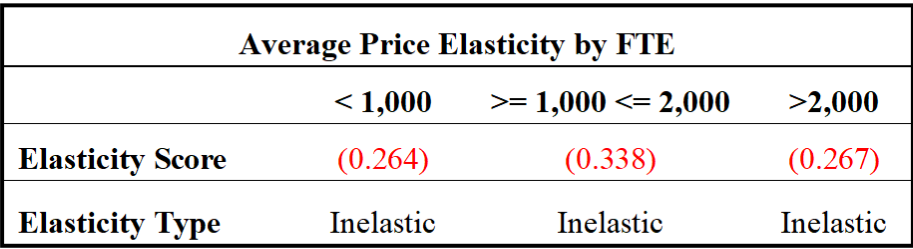

Now let’s turn to what the most recent data says about price elasticity in higher education and its impact on demand. Table 1 gives the price elasticity for three FTE enrollment groups (less than 1,000 FTE, 1,000 to 2,000 FTE, and more than 2,000 students). Price is inelastic in each group, which suggests that changes have little or no effect on enrollment decisions.

Table 2

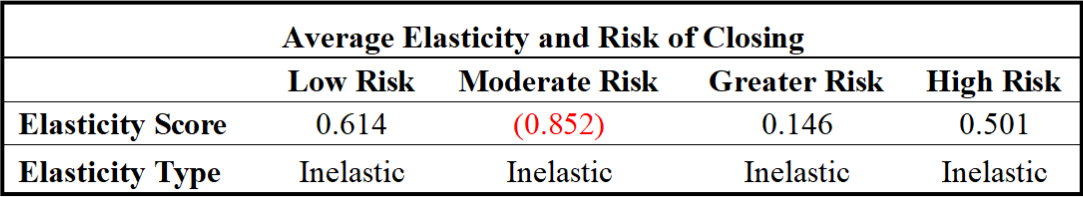

The next table has the elasticity score and type for four risk rands. Each risk band (low, moderate, greater, and high-risk bands) represent a probability that estimates the chance of closing in the near future. The score range runs from 0.0 to 1.0 probability of closing for all four risk bands. All four bands are inelastic, as it was with the three FTE groups in Table 2.

Table 3

The elasticity scores of these two tables imply that tuition discounts will not generate sufficient net tuition revenue to offset the expense of the discount. Chart 3 illustrates the problem that the average private college must consider the impact of price elasticity when setting values for: posted tuition, tuition discount, enrollment forecasts, and budget revenue estimates. The charts indicate the average five-year changes in tuition revenue, discounts, net tuition revenue, and FTE enrollment as follows: tuition revenue was up 7.4%, tuition discounts grew 31.3%, net tuition revenue shrunk 11.7%, and FTE enrollment increased 5.1%.

As the preceding discussion on elasticity posits, and given that the average college is price inelastic, it should not be surprising that the average college did not generate enough new student revenue to offset the cost of the tuition discount.

The findings on elasticity and net tuition revenue suggest that tuition discount strategies are not the way to go, if a president and board want to avoid joining the colleges in Chart 1 that have fallen off the cliff. Other places where the leadership could focus its efforts would be: cost cutting, new programs, merger, and not waiting until the last minute to solve their financial problems. If there is one aspect that many closed colleges have in common is that they waited too long to figure out a new strategy. Another common mistake among presidents in looking for solutions is that they talk with other presidents who have the same problems and also do not have workable ideas to stop the rush to the edge of the cliff.

Chart 3

There is one last note about pricing and that is pricing power in the marketplace. Pricing power is evident when a specific institution can set the posted and net tuition price and other college follow in their pricing strategies. Those institutions would be called price makers. While the price follower institutions are called price takers. The later have very little control over their pricing strategies. The price taker must like the above comment about inelastic pricing failures over the past five years, must focus over other areas to improve their capacity to compete and survive in the higher education market.