by Michael K. Townsley | Sep 7, 2024 | Financial Metrics, Measuring Financial Condition

Private colleges and universities are encountering unprecedented levels of financial stress that may even exceed the financial problems caused by the Great Depression in the 1930s. According to the Hechinger Report article in April 2024, “colleges are closing at a pace of one a week.[1] Sustainability for many colleges means whether they can survive the immediate financial stresses. “Fitch ratings estimated that 20-25 schools will close annually going forward.”[2] However, as of August 2024, thirty-three colleges have already closed which is well beyond the Fitch forecast.

The main financial problem for many private colleges is the continuing decline of average Unrestricted Net Assets. These assets are used for payrolls, other operational expenses, and debt service. After a small increase in the in average assets in 2018, they began a steady decline in 2019 until they hit their lowest level in the chart in 2020. The culprit for reaching the lowest average of Unrestricted Net Assets in 2020 can be traced to the COVID pandemic, when colleges had to close. Despite, COVID’S devastating effect on these assets in 2020, they came roaring back in 2021, when large governmental (federal and state) funds arrived to save the day. Nevertheless, average Unrestricted Net Assets collapsed in 2022 with their value nearly returning to the 2021 COVID level. As Bloomberg reported in 2023, “…government aid during the pandemic helped as a Band-Aid on the long-simmering issue of dwindling enrollments, the expiration of relieve(sp) next year (2024) is likely to expose that a reckoning is already playing out at dozens of colleges.”[3] Sad to say, the chickens are coming home to roost.

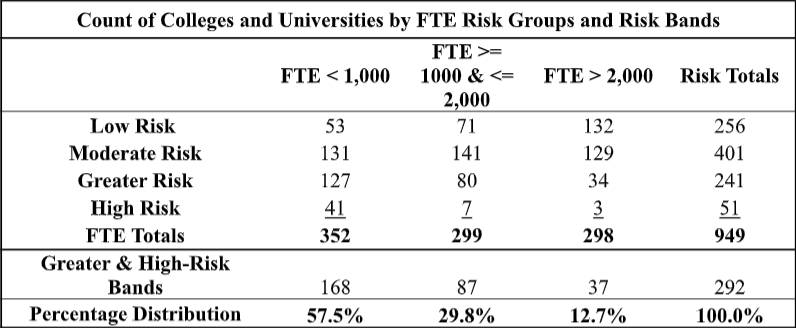

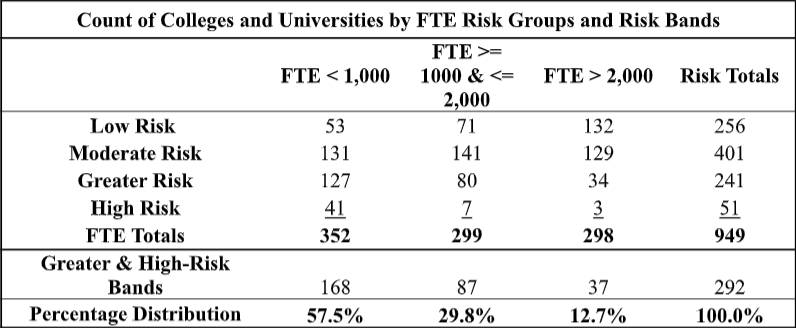

The Vulnerability Guage©, which predicts financial failure was applied to a data set of 949 private colleges, to predict financial risk for three FTE enrollment groups and four risk bands. Table 1 shows that the distribution of colleges by each enrollment group is nearly equal with 37% in the smallest group, 32% in the middle group, and 31% in largest group. However, financial risk as measured by the ‘Greater Risk and High-Risk Bands’ are not equally distributed. Private colleges with enrollments less than 1,000 FTE students were assigned to the ‘Greater and High-Risk Bands’. The next two enrollment groups, FTE 1,000 to less than 2,000 and FTE greater than ,000 FTE respectively had 29.8% and 12.7% assigned to the ‘Geater and High-Risk Bands’. To recap, colleges with enrollments less than 1,000 FTE students face the greatest risk of financial failure.

The following chart shows more clearly the relationship of enrollment and financial risk.

Because many private colleges have felt the full-force of falling enrollment, they can no longer count on tuition revenue to generate the net revenue or cash to support operations and capital expenses. The next chart illustrates what has happened to net tuition since 2016. Although the last year of the chart is 2021, it is probably a fair assumption that net tuition has not increased given that NACUBO reported average tuition discount for private colleges was 56.1%. This was 2% higher than in 2021. Larger discounts mean less cash.

Final Comments

Higher education, in general, and private colleges and universities, in particular, faces a woeful future as slackening demand, rising costs, and excess supply of seats grinds down their financial stability. In most cases, catastrophic conditions did not suddenly appear. They have been present, since student market demographics began their downhill slide at the start of this century. (See the Bloomberg essay, “The Economics of Small US Colleges Are Faltering”)[4]

The preceding discussion suggests that only small colleges are in danger. This is a false assumption because even some medium and large private institutions are rated as high risk. Moreover, with declining enrollment medium and large institutions can slide into the small college column and be subject to higher financial risk

Final comment: Time is of the essence; delaying action does not diminish the factors shaping financial risk for a specific private college or university.

References

-

Marcus, Jon (April 26, 2024); “Colleges are now closing at a pace of one a week”; (Retrieved April 30, 2024); The Hechinger Report; Colleges are now closing at a pace of one a week. What happens to the students? – The Hechinger Report. ↑

-

Querolo, Nic (December 13, 2023); “The Economics of Small US Colleges Are Faltering; (Retrieved April 30, 2024); Bloomberg; US Small Colleges Battered by High Costs, Enrollment Declines (bloomberg.com). ↑

-

Querolo, Nic (December 13, 2023); “The Economics of Small US Colleges Are Faltering; (Retrieved April 30, 2024); Bloomberg; US Small Colleges Battered by High Costs, Enrollment Declines (bloomberg.com) ↑

-

Querolo, Nic (December 13, 2023); “The Economics of Small US Colleges Are Faltering; (Retrieved April 30, 2024); Bloomberg; US Small Colleges Battered by High Costs, Enrollment Declines (bloomberg.com). ↑

by Michael K. Townsley | Sep 7, 2024 | Financial Metrics, Measuring Financial Condition

Economic equilibrium for a college or university is a state of long-term financial sustainability. Richard Cyert, late President of Carnegie Mellon University and a noted economist, originally developed the concept. This paper treats Economic/Financial Equilibrium as analogous to. Economic Equilibrium.

Economic/Financial Equilibrium Model

- Premises- Equilibrium:

- Is subject to the mission of the institution

- Should support the mission of the institution.

- Requires dynamic and positive states of positive financial change (net income and net cash must increase) in the short and long-term

- Financial changes must be large enough to offset inflation and to provide sufficient financial reserves when there are unexpected changes in markets, technology, and governmental regulations.

- Equilibrium Conditions1:

- There is sufficient quality and quantity of resources to fulfill the mission of an institution.

- Equilibrium maintains

- The purchasing power of its financial assets.

- Its facilities in satisfactory condition.

- Disequilibrium is a financial state when there are insufficient financial resources to maintain financial assets and to keep facilities in satisfactory condition.

- Difference between equilibrium and disequilibrium is the ‘equilibrium gap’.

- Reaching a state of financial equilibrium requires identifying and eliminating the causes of disequilibrium.

Disequilibrium usually does not occur overnight and most likely is due to long-term conditions that lead to the erosion of cash reserves, short-term loans, endowment principal, and plant value. When the financial condition of a college or university has so eroded that its cash and financial reserves have been seriously depleted, designing a strategic plan to achieve equilibrium is difficult.

Easy decisions, such as raising tuition or cutting expenses across the board, can be counterproductive if it pushes the college outside its competitive boundaries (that is, the set of colleges that compete to enroll the same students). As Richard Cyert noted,

“The trick of managing the contracting organization is to break the vicious circle which tends to lead to disintegration of the organization. Management must develop counter forces which will allow the organization to maintain viability.”2

In sum, boards of trustees must expect presidents and chief financial officers to clearly show that the college is currently in economic-financial equilibrium and will remain in equilibrium in the future. In addition, the board has a fiduciary responsibility to provide the president with the authority, subject to legal constraints, to take strategic and operational action to achieve economic/financial equilibrium.

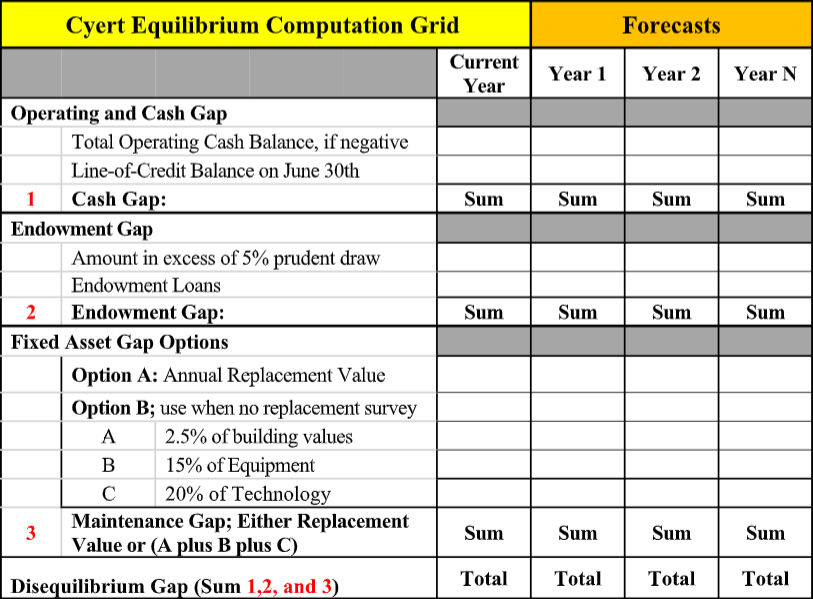

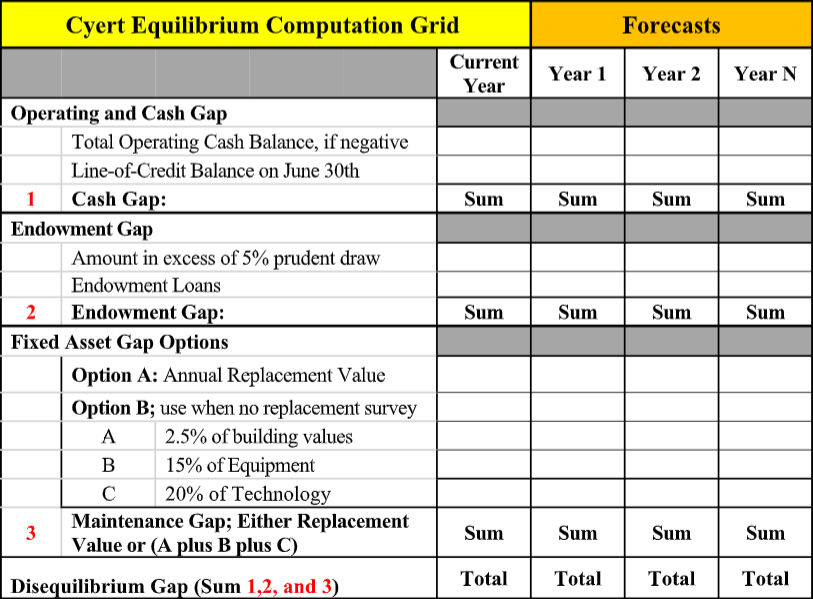

Template for Estimating the Disequilibrium Gap

The preceding template provides a means to identify the scale of disequilibrium. In addition, it allows the analysis to extend beyond the current year when contracts and other constraints impose costs leading to continuing disequilibrium in the future.

Common Strategies for Eliminating an Equilibrium Gap

- Enrollment, Recruitment, and Retention

- Enrollment, recruitment, and retention strategies requires analysis of current academic programs and the characteristics and goals of the prospective student market.

- Tuition discounts, since discount strategies have increased beyond their net cash value, any further increases in discounts must be carefully evaluated and carefully targeted as a competitive strategy.

- Marketing campaigns must precisely target prospective students with all forms of media and aggressively recruit students considering enrollment with a competitor.

- Retaining students is an imperative given the cost of replacing an attrited student. .

- Enrollment strategies should be guided this basic financial goal: net student revenue (net tuition plus net auxiliary revenue) must increase net cash.

- Gifts

Gift agreements should be written to reduce loan liabilities. At many private colleges, debt service makes-up a large portion of the Cyert Gap. Furthermore, the gift/advancement department should meet with prior donors and request permission to use their endowed gifts to reduce the pay down loans. Prior donors could be offered the bargain that the college would establish a scholarship in perpetuity in lieu of using the funds to pay down current loans.

If the size of the disequilibrium gap is so large that neither increases in enrollment nor cutting expenses will eliminate the gap, then the college should appeal to the state’s attorney general to allow a loan against the endowment.

Investment committees have conflicting preferences because they are expected to maximize endowment returns over the long term. A long-term investment strategy is valid if the gap is not massive. However, if cash deficits are so large that the

college faces the distinct possibility of closure; the investment committee must change its investment priorities to generate short-term cash flows.

Too many colleges and universities ignore deficits produced by auxiliary operations. At a minimum, auxiliaries should cover their direct expenses plus related capital expenses. If the auxiliary cannot achieve this elementary financial goal, then the institution should outsource money losing auxiliary operations.

Cutting costs is essential for institutions at disequilibrium. Usually, a college will find that new revenue is insufficient to close an equilibrium gap. Under those circumstances, the college must evaluate every expenditure, be it, chief administrative positions, academic programs, student services, or third-party contracts. In some instances, the president may need to take over a chief administrative role, such as the provosts or chief academic officer roles, until the gap is eliminated.

Too often, presidents and chief administrative officers waste their scarce time and the colleges scarce resources tinkering around the edges of the operations. If the college is heavily loaded with debt, a first priority should be to refinance the debt to reduce debt service expenses and to reduce collateralization that, in some cases, restricts the sale of college assets.

Summary

Economic/Financial equilibrium requires constant and regular monitoring of key activities by the board of trustees and the president. Equilibrium plans may require soul searching to determine if how the college can best serve the mission of the college and retain its financial viability.3

Final Points

- Economic Equilibrium is reached when an institution can fulfill its mission with adequate quantity and quality so that it retains its purchasing power while maintaining the conditions of its facilities and equipment so serve its students.

- The primary financial goal for tuition-driven private colleges should be to achieve a dynamic state of economic equilibrium that looks beyond the current year.

Economic/Financial equilibrium strategies must be continuously monitored and revised to accommodate changes in: the mission of the institution, student markets, academic programs, financial assumptions, and major changes in the economy or in financial markets.

References

1 Ruger, A., J. Canary, and S. Land.; (2006); “The President’s Role in Financial

Management” in A Handbook for Seminary Presidents; edited by G. Lewis and L.; William B. Erdman Publishing Company; Grand Rapids, Michigan.

2 Cyert, R. (July, August 1978); The Management of Universities of Constant or Decreasing Size; Public Administration Review; p. 345.

3 Townsley, M. (2002); The Small College Guide to Financial Health. Washington, DC: NACUBO; p. 180

by Michael K. Townsley | Sep 5, 2024 | Financial Strategy and Operations, Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis

Introduction

For the past decade, our colleagues and columnists have remorsefully muttered about friends in terminally ill colleges. Now, we know “for whom the bell tolls.” As more old colleges are thrown on the death cart, other small colleges only wait and wonder if their college is next to be chucked on the heap of history.

This paper introduces a Vulnerability Gauge to predict if a private college or university is or is not at risk of financial failure. A logit regression tested the model with several different combinations of variables. The model was applied to a random sample of forty-four private colleges and universities drawn from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). database. The tests found the most robust and parsimonious model had an 86.3% prediction rate of financial risk when these two factors were used:

- Annual percentage change in unrestricted net assets over five-years (for most private colleges, these assets represent the ready financial reserves that cover operational expenses);

- The total change in FTE (full-time enrollment) over five-years.

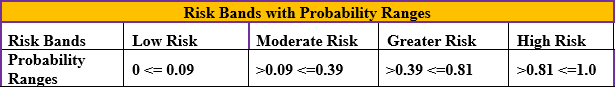

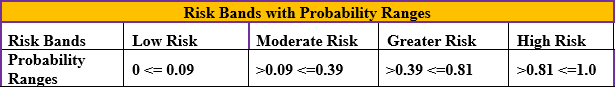

The logit regression yielded the probability of financial failure for each school in the sample. The probabilities were then arrayed into four risk bands: low, moderate, greater, and high risk of financial failure as shown in Table 1. The risk bands indicate that the lower the probability, the lower the risk of closing and the higher the probability, the greater the risk of closing.

Table 1

Risk Bands of Probabilities for Study Sample

Findings from Large Sample Analysis of Unrestricted Net Assets and Enrollment

After the random sample was tested, the model was then employed to test the vulnerability of 949 private colleges that were open in 2016. This sample excluded medical schools, research institutes, arts programs, seminaries, and other specialty colleges. The analysis covered the period 2016-17 to 2021-22, which was the most recent year in which IPEDS higher education data was available.

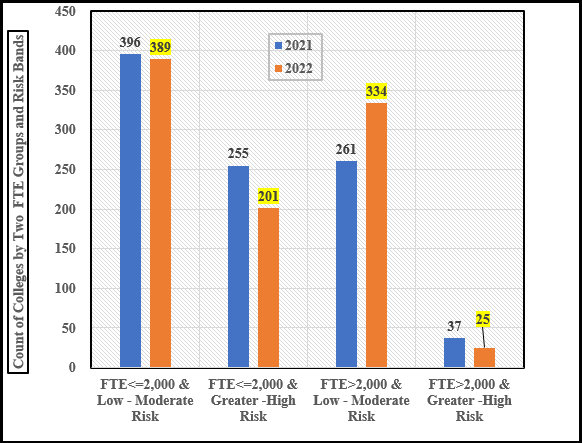

Chart 2

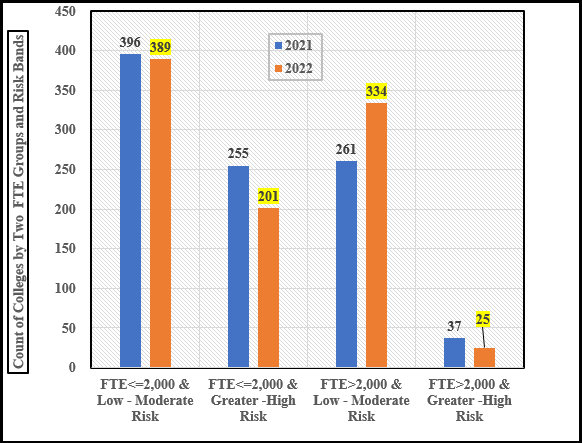

Colleges Assigned to Two Classes of Risk and Enrollment for 2021 and 2022

Here are several observations from Charts 2:

- In 2021, 255 private colleges with less than or equal to 2,000 students were rated at greater to high risk, but only 37 colleges with more than 2,000 students were rated with the same risk. In other words, institutional size seems to be a major factor in determining risk. In 2021, the risk rating for small colleges was 6.9 times greater than for larger colleges.

- In 2022, 201 more smaller colleges than larger rated as greater to high risk, 54 fewer colleges than in 2021. Yet, the greater to high-risk rating for smaller colleges was 8.0 times larger than larger colleges.

- In 2022, the enrollment group with more than 2,000 students saw seventy-three more colleges rated as low to moderate risk, in comparison to 2021, but this group had twelve fewer colleges rated as higher to greater risk.

Conditions Unique to Higher Education that Degrade Response to Risk

Before any remedy can be prescribed, we need to understand why so many private colleges are slow to respond to economic and financial threats to their existence. The list at the start of this paper identified several factors that shape financial stress, but there are further internal and operational issues that also shape the financial vulnerability at small private colleges. See the following list of issues that may foster financial stress.

- Contradictions of dual governance, where major academic financial problems, and their solutions may be stymied by conflict between how faculty and administration govern their respective areas.

- Faculty tenure that places costs, sometimes substantial, for the dismissal of faculty due to a major reorganization and the termination of academic majors or programs.

- Explicit and implied contracts with students, faculty, and external parties in student handbooks that set out the liability to students when programs, athletic programs, student services, or dormitories are ended or downsized, faculty handbooks that specify work conditions, alumni traditions that carry costs, or unstated relationships with local governments that have inherent costs.

- Accreditation and governmental regulations that may stipulate financial conditions to sustain operations and standards for academic programs and student services that can a) raise the cost of operations and b) make it difficult to change academic programs. Governmental regulations can also stipulate financial conditions and standards for maintaining eligibility for federal funds or for compliance with federal mandates.

- State Non-Compete Regulations can keep a college from offering a new program if another institution already offers it.

- Human Capital, buildings and equipment may not match what a college needs during a strategic reorganization to serve its student market better while reducing costs.

Besides the preceding organizational failures, leadership failures by the president and board of trustees to reshape a private college’s capacity to rapidly respond to financial crisis and reducing financial vulnerability

Potential Remedies for Reducing Financial Risk

Responding to the highest level of financial risk requires information that delineates the financial, operational, and market conditions of the institution. Before diving into strategic and operational turnaround strategy, the president and board need to acknowledge whether or not operational deficits have become a recurring and increasing threat. In the next step, both the board and president need to know the level of financial reserves currently available, whether those reserves are expanding or shrinking, and how long those reserves will last, if there are operational deficits. Also, there is no surer sign of performance inefficiency than a major with three or more full-time faculty instructing four students in a major.

It is imperative for Boards to recognize the need to support Presidents who lead with fortitude, intelligence, and foresight, otherwise it will be difficult for the institution to withstand conflict generated by internal and external dissension in response to major strategic changes. Conflicting solutions and dissension could become a regular event. Nonetheless, every day lost, before taking steps to overcome the inertia toward failure, will push the college closer to its demise.

The factors that make up the Vulnerability Gauge can guide the development of an effective strategy to generate larger and positive net incomes that increase unrestricted net assets. Focusing on factors in the Vulnerability Gauge will lead to optimizing markets, generating higher cash flows from tuition, cutting administrative expenses, improving the financial and operational relationship between faculty and students, imposing controls on the operational efficiency of capital investments in grounds, buildings, and equipment, and moving revenue generating centers toward positive contributions to the bottom line.

For colleges that have arrived at the brink of survival, there seem to be three strategic options that colleges at the brink of extinction consider:

- Merger

- Forming a partnership;

- Looking for wealthy alumni or local donors.

To access the Vulnerability Gauge, Go To: Education Consulting & Strategic Planning for Colleges & Schools – Stevens Strategy