by Michael K. Townsley | May 22, 2022 | Enrollment and Marketing

NACUBO Warns – Enrollments May Be Declining with Tuition Discounts

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

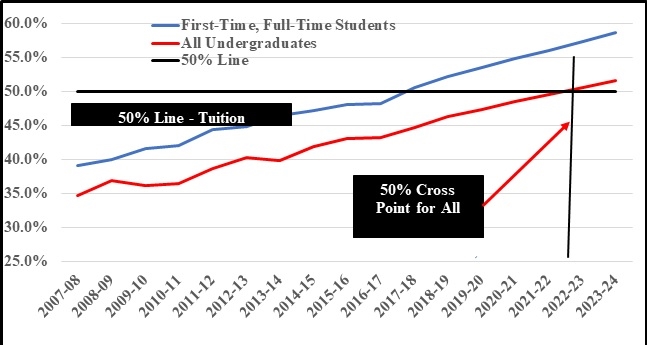

NACUBO just published its survey of tuition discounting and the results are disturbing. For the first time, a number of private colleges reported that new student enrollment declined despite increases in a tuition-discounting program. Over the past several decades, tuition discounting strategies have provided private colleges with a mechanism to increase tuition by 2% over inflation while deflating the increase for new students through higher tuition discounts.

When tuition discounting strategies stop working, new student revenue drops and net tuition revenues fall below expectations. Failed discounting strategies will quickly undermine the budgetary and financial stability of many private colleges.

There are two possible reasons that may explain why tuition discounting strategies are losing their punch. The first is based on the underlying economics of discounting strategy and the second is possibly due to diminishing returns with tuition discounts. This blog will talk about why the economics may be changing and how the tuition discount algebraic expression could accelerate the problems with lost net tuition revenue.

Economic Premise Underlying Tuition Discounting – Price Inelasticity

The basic economic premise underpinning tuition discounting is that students are price inelastic. This means that if discounts do not reduce tuition below the previous year’s tuition rate, an increase in tuition will not result in a loss of student revenue. More than likely, if the new tuition level leads to a drop in new student enrollment, it will be small and the higher tuition rate will offset the loss.

Why are students’ price inelastic? Students in the past have not been price shoppers. They tend to pick a college based on hearsay or recommendations from friends or family. Also, students have not needed to shop around because tuition could be paid from savings or discretionary income or, if they borrowed money, they did not accumulate large amounts of debt. Also, until recently, students finished their degree at the college where they first enrolled. They did not transfer elsewhere because transferring credits was too difficult and their personal investment in their own academic credits and social network were too high to forego.

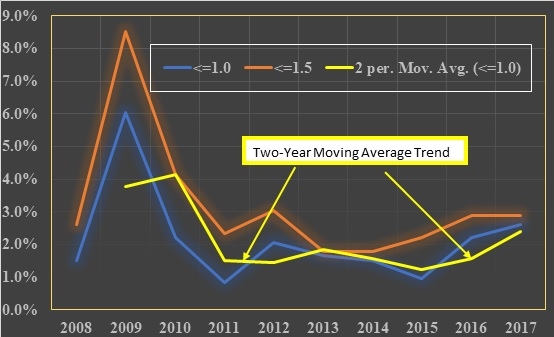

When tuition discount strategies were well-behaved (as in Chart I), enrollments grew and total tuition revenue increased. Presidents and Chief-Financial-Officers counted on tuition strategies to produce anticipated patterns of tuition income flow, which led to budgetary and financial stability.

Chart I

Well-Behaved Discounting: Tuition Net of Inflation (0%). Annual Increment (5%) and Discount (base year discount: 42% with annual tuition increment of 1%) Compared to the Net Tuition Rate

Are Students Becoming More Price Elastic?

Recent evidence suggests that students and their parents have become aggressive shoppers looking for the best price. As colleges ease their rules in accepting transfer credit, they are encouraging students to continue to shop for the best deal, be it price, academic programs, sports, or amenities, even when they have already enrolled and earned credit. The best deal may encompass more than price. One of the unexpected outcomes, with the increasing probability of transfers, is that colleges are forced to deal with both new students and keeping their currently enrolled students. Shopping by both new and enrolled students suggests that price inelasticity is waning as students become more price elastic. Greater price elasticity will distort the customary tuition discount strategy of jacking up tuition prices then discounting it to new students. Price elasticity suggests that higher tuition levels will drive students to find cheaper alternatives and that they may prefer easily understood posted prices rather than complex financial aid packages.

The Tuition Discount Formula Contains a Kicker

The tuition discount strategy typically has two components, a rate of change for tuition and a rate of change for tuition discounts. As price inelasticity wanes and is replaced by greater price elasticity, a quirky aspect of the tuition discount strategy rears its ugly head.

When price elastic conditions prevail, tuition discount strategies incorporate a kicker. The kicker becomes apparent because static enrollment no longer masks the tendency of the tuition discount to produce diminishing returns and negative dollar changes. This perverse aspect of tuition discounting is readily evident in Chart II.

Chart II

Hidden Kicker: Tuition Net of Inflation (3%), Annual Increment (5%) and Discount (base year discount: 42% with annual tuition increment of 1%) Compared to the Net Tuition Rate

Under the inflationary, incremental tuition, tuition discount, and static enrollment conditions in Chart II, posted tuition has a nice positive slope. However, net tuition rate exhibits an alarming negative slope. As price elasticity takes hold, more colleges will find that as the enrollment mask is stripped away, net tuition rate will generate diminishing returns. By implication, diminishing returns for the net tuition rate will carry through to diminishing returns for net tuition revenue. Chart III clearly illustrates how marginal changes (diminishing returns) have a very steep and negative slope. Presidents and Chief Financial Officers need to be worried about diminishing returns when tuition discounting strategies stop working; i.e., enrollment no longer increases as net tuition rates increase over time.

Chart III

Effect of the Hidden Kicker on Marginal Change in Net Tuition

Private Colleges Should Take Prudent Steps to Build New Financial Strategies

For years, private colleges have been able to have their cake and eat it too by raising tuition faster than inflation and then partially reducing the impact through tuition discounts. If tuition discount strategies are losing their capacity to generate new net tuition revenue, then it is prudent that private colleges, especially financially weak institutions, consider alternatives to the classic tuition discount strategy. Moreover, government and media criticism about rising posted tuition charges only adds pressure to colleges to find new ways to fund the delivery system for education without depending upon never ending increases in tuition rates.

What Should Colleges Do If the Tuition Discount Strategy Is Becoming Obsolete?

Private colleges will need a different perspective if they intend to develop new funding strategies and to deal with governmental oversight on tuition prices. Here are several strategies for managing tuition pricing that Stevens Strategy has implemented with our clients.

- Responsibility Centered Management (RCM) Analysis: this service identifies programs that generate sufficient net income to support the general operation of the institution. This analysis can be the basis for developing expense allocation strategies, cost controls, and new income producing programs.

- Programs and Resource Optimization (PRO): adds mission centeredness and quality and marketability reviews to the RCM analysis.

- Operational Cost Analysis: this service pinpoints cost efficiencies and inefficiencies.

- Financial, Marketing, and Operational Reviews: Stevens Strategy works closely with the President and Chief Operations Officers to review current financial, marketing, and income production strategies, practices, policies, and operational systems to determine if they support the mission of the institution, generate adequate income, and provide a smooth-running cost-effective operation.

- Financial Health Checkup: this service involves a thorough evaluation of financial conditions both short- and long-term to determine if financial stability is improving or declining.

- Equilibrium Analysis: this service focuses on the strategies needed to achieve economic equilibrium given known economic, financial, regulatory, competitive, and operational conditions.

Stevens Strategy recommends that Presidents and Chief Operational Officers conduct a careful review of their institutional discounting strategies, plans, and performance data. Our firm can assist you in conducting the review and provide recommendations on changes that may need to be made to manage and control tuition and discounting strategies.

by Michael K. Townsley | May 22, 2022 | Presidential Leadership

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

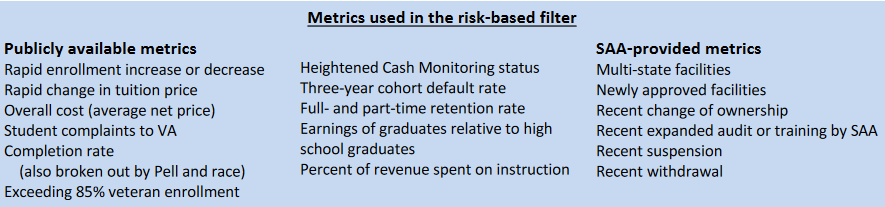

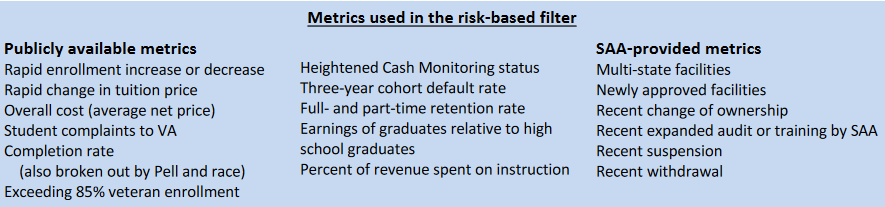

The February 2, 2022 issue of Inside Higher Education carried the article “Using College Outcomes to Gauge Risk for Students” by Doug Lederman. [1] The article addressed how to protect veterans from choosing a college that might not survive. The article reviews several measures to identify the potential signs that a college might fail. This blog will comment on assumptions of the underlying measures of college survival and the validity and construct of those measures. The article includes these “metrics used in the risk-based filter.”

The article does point out a fundamental political question raised by Rebecca S. Natow, Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy at Hofstra University:

“She said via email that an accountability regimen that applied to all colleges and universities …would struggle to gain the sort of bipartisan support that measures about veterans do.

The two main political parties have been much less likely to agree on accountability policies affecting Title IV programs more broadly, such as the gainful-employment rule, Natow said. It could be brought about through executive action, as much federal policy making in higher education has been [recently], but that typically results in legal challenges and flip-flopping as a new administration takes office.

Leaving matters in the states’ hands, in contrast, typically results in vastly uneven regulation, with some states being rigorous and others less so, Natow said.”

Moreover, another broad assumption is that government bureaucrats would enforce regulations to constrain risk. Instead, bureaucrats might determine that the greater risk is to themselves because enforcement could see the demise of institutions that are supported by powerful interest groups and by formidable political leaders. One example of this phenomenon of non-enforcement of risk regulations is that year after year the same colleges fail the Department of Education (DOE) ‘Financial Responsibility Test,’ yet the DOE rarely takes action.

General Comments: This section covers several significant sources of inefficiency.

- Managing risk in higher education assumes that colleges are attuned to factors that increase risk and that they have the power to control them.

- An important problem with nearly every metric and model of risk is that they are not rigorously tested to evaluate if they are valid. Too often the models are victims of post hoc analysis because they don’t take into account colleges that have closed.

- Of course, the main question regarding risk is how to define risk in higher education. Richard Cyert provides a way into understanding that risk. According to Cyert, a college needs to reach a state of economic equilibrium to assure its long-term survival. According to his model, financial equilibrium occurs when there are sufficient resources to sustain an institution’s mission for current and future students.[2] Therefore, risk would be the probability that the financial resources of an institution could or could not sustain the academic program (assuming that academic programs are the primary mission of the institution) for current or future students.

Comments about Risk Metrics and Models:

- Risk metrics are burdened by the inherent problems associated with the excessive aggregation of institutional data that limits the capacity to clearly identify issues below the broadest institutional levels. In other words, because refined data is not available, models and metrics too often assume that available and overly aggregated data will be valid predictors of risk.

- Over the past several decades, financial risk has been measured by importing business ratios. The assumption is that business ratios can capture the financial condition of an institution of higher education. However, business rates are designed to measure risk in terms of the capacity of the enterprise to generate sufficient cash flow to sustain on-going operations. Colleges, on the other hand, can and often survive for decades on the cusp of financial disaster as measured by business ratios because annual gifts, new government funds, or donors who make large gifts repeatedly pull an institution’s chestnuts out of the fire.

- Even though some colleges have survived for years as mere husks of an institution of higher education, these institutions often fail to achieve Cyert’s equilibrium condition that colleges need sufficient resources to support their mission and to serve their students for the short- and long-term. When colleges are merely husks, they too often may produce a degree with little or no value to graduating students.

- Certain risk-filter models hypothesize that they can forecast grave risks using seven or more years of long-term data for predictor variables. The problem with these models is it they assume that the predictor variable is continuously downward sloping. While these models may identify some institutions at risk, they often miss many institutions where early data may be positive, and then due to external or internal conditions, the predictor data suddenly turns negative. Regrettably, the adverse effect of a short-term and hazardous decline in a predictor variable may be dampened by earlier positive performance using long-term data. The best way of testing a risk-filter model is to test it against a data set that includes institutions that have already failed. Sadly, this data is often hard to locate because when institutions close, they are no longer identified in data sets.

Risk Based Filter Metrics Included in “Using College Outcomes to Gauge Risk for Students”

The following table is from the Inside Higher Education article, which includes risk metrics that were being considered by the Veterans Affairs Administration to protect veterans from enrolling in a failing college. These metrics are also commonly found in other risk models. After the table, there are several comments about the Veteran Affairs metrics suggesting which metrics are the most and least valuable.

The following risk-based factors are of modest or no value in determining short-term risk:

- Rapid enrollment increases or decreases: This metric is used in risk models and financial reviews, because for most private colleges and universities enrollments are the main drivers of revenue. If the period to measure the change in enrollment is too long, the change within the period may mask real problems in a shorter time frame. Change in enrollment is a worthwhile metric only when compared to changes in direct expenses (instruction, student services, and academic support).

- Rapid change in tuition price: this measure is an insufficient measure of risk because it does not get at the price paid by a student. The metric Overall Cost does measure the cost to a student.

- Completion rate (by Pell and race): This is a pertinent measure for government agencies to determine if their investment in a college is producing value for veterans. Moreover, prospective students may choose not to enroll at an institution with high attrition and low graduate rates. This measure is not a valuable risk metric of short terms risk because it requires data collected over a long period of time.

- Exceeding 85% VA enrollment: This metric is a VA regulatory measure to limit funding to an institution that mainly focuses on veterans, but it does not measure risk of institutional failure.

- Three-year cohort default rate: The presumed default rate is on federal loans. The underlying assumption is whether prospective students will continue to enroll if they graduate with loan balances that cannot be paid from their income. This metric might be useful in the long-term assuming that prospective students take earning after graduation into account when they agree to loans. However, the effect of the three-year cohort metric may become evident only after the college or university is already about to close due to other factors.

- Earnings of students relative to high school graduates: This metric is both an institutional and an academic program issue. The question is: “What is the point of enrolling in a program if a degree has no more (or even less) value than a high school diploma?” This issue is also germane to institutional marketing efforts. Assuming that future earnings from an institution or a program are known to prospective students, many will reject the choice if future earnings are insufficient to cover future expenses, as was noted in the default rate comment. This metric would be useful in analyzing programs in a long-term analysis, but it may have little practical value as a measure of short-term institutional risk unless all or most of the institution’s programs have little relative economic return in comparison.

- Percent of revenue spent on instruction: The assumption here is that as the percentage of money for instruction decreases, the quality of instruction also decreases. However, innovations in instructional delivery can reduce costs and increase quality. Instructional expenses can decrease at colleges that allocate more funds for student services and academic support to improve retention and graduation rates. ‘Percent of revenue spent on instruction’ as a risk metric is too limited.

- Note that the SAA metrics are mainly of interest to accreditors or government agencies and are not discussed here.

The following risk-based factors are of effective value in determining short-term risk:

- Overall Cost (average net price): This metric represents the out-of-pocket costs that veterans are being charged. If the metrics in the table are intended to measure risk, then this metric can illuminate the cash flowing from enrollment to cover direct costs. Multi-year evidence shows that while tuition net of institutional grants has fallen (in other words, students are paying less out of pocket), direct costs have been increasing. This means that the risk to the institution is increasing as net tuition declines and direct costs go up.

- Student complaints to VA: This is a good way for the VA to identify problems because the complaints are coming directly from students enrolled in a college or university.

- Heightened cash monitoring status: This metric gets at the central issue of whether an institution can survive. If a college or university does not have sufficient cash reserves to cover on-going operations and debt-service, then they may have to turn to lenders for short-term loans. If short-term loans increase in size over time, then the institution is at risk when unexpected events like the Covid pandemic occurs.

- Full and part-time retention rates: As retention rates fall, the need to find new students to bolster enrollment, along with associated marketing costs, increases. In addition, there is a possibility that falling retention rates imply that the academic programs are not designed to reach the academic skills of the students enrolled by the college. This metric also ties into the discussion about ‘Completion Rates’.

Several Other Metrics That Measure Risk Effectively:

Here are several risk metrics that could be used independently or assembled into a model:

- Net Student Revenue: If the sum of tuition net of institutional grants plus auxiliary income (excluding hospitals) and net of expenses is increasing, Net Student Revenue yields more funds for operations, while shrinking Net Student Revenue reduces capacity to support operations, which places the institution at risk.

- Net Student Revenue to Direct Expenses (instruction, student services, and academic support) Ratio: An increasing Net Student to Direct Expense Ratio is able to support a greater proportion of direct expenses or even produce excess revenue to cover indirect costs (ex. institutional support, plant, debt, etc.). A decreasing ratio reduces the proportion of funds available for direct funds and puts pressure on the college to find other sources of revenue, which is often not possible for tuition dependent colleges, thus placing the institution at risk.

- Class Size Ratio (the average number of students in front of an instructor): The larger the class size the greater the net direct instructional revenue and the smaller the class size the lower the net direct instructional revenue, increasing institutional risk.

- Class size in classes required by a major: Very small class sizes indicate that the major is not supporting the operational costs associated with the major. The greater the number of these underutilized majors, the greater the institutional risk.

- Net Tuition Revenue plus grants to Operational Costs of a Major Ratio: A small or declining ratio suggests that the major is unable to support itself. The more the number of these majors, the greater the institutional risk.

- Space Usage Ratio: This ratio measures the percentage of building space used during a fully employed period of sixteen hours. A low usage ratio suggests that building space is not fully optimized to cover debt service, operational costs, or repair and maintenance, and is an indicator of future risk.

- Cash Flow Metrics: As indicated in the preceding section under the heading “Heightened cash monitoring status,” cash is a common metric in measuring risk. Here are several ways to measure if the college is building or depleting its cash reserves:

- Cash Flow from Operations: This metric is found in audit reports and shows cash is the main reserve from which operations are supported.

- Cash from Operations to Net Change in Assets from Current Operations: This measures whether operations are increasing or depleting cash.

- Total Cash: This shows if the college is building its cash reserves from all sources of cash. It also measures if trends in total cash are increasing or decreasing.

- Negative cash trends are a definite indicator of future risk.

Risk Management – Preserving the Mission

If risk is defined by Cyert’s proposition that colleges risk their capacity to deliver on their mission if they do not have sufficient financial reserves, then the question arises: “How does an institution reduce its risk?” Colleges and universities can reduce risk by determining whether or not their mission is achievable given the resources that they have available. This proposition suggests that the following questions need to be addressed:

- What is the mission of the college?

- Does the mission fit the demands (expectations of students)?

- Does the mission need to be reconstrued to respond to the student market?

- If the mission needs to be rewritten, will the corporate by-laws support the change in the mission or do the by-laws need to be modified?

- Do academic programs need to be revised to respond to the expectations of students?

- Should resources, both fiscal assets and personnel, be reallocated in response to changes in the mission and academic programs?

- Ought the administrative footprint and physical assets be restructured or eliminated to release resources toward instruction and instructional support?

- What is the enrollment and net tuition price point needed to generate the funds needed to operate new academic programs and build financial reserves?

- How should marketing strategy and actions be redesigned to support changes in the mission, enrolled students, and academic programs?

There are many more questions that may need to be answered to perfect models of risk. Nevertheless, the economic environment reshaping higher education today makes it necessary to address these questions sooner rather than later.

ENDNOTES

-

Doug Lederman; (February 2, 2022) “Using College Outcomes to Gauge Risk for Students”; Inside Higher Education; A possible model for identifying riskiest colleges for students (insidehighered.com). ↑

-

Townsley, Michael (2014) Financial Strategy for Higher Education: A Field Guide for Presidents, CFOs, and Boards of Trustees; Lulu Press; Indianapolis, Indiana; p. 15. ↑

by Michael K. Townsley | May 22, 2022 | Financial Strategy and Operations

Chief financial officers (CFO) are gatekeepers for the financial resources that fund the mission of the institution. CFOs are more than a necessary evil to keep the money straight. They have a keystone role in the institution because their education, experience, and responsibilities give them unique insight into the quality and quantity of resources needed to support the mission. Their fundamental obligation is the management of the financial resources of the institution. How CFOs carry out this responsibility is the theme of this blog.

The chief financial officer and the president have complementary authority and responsibilities that reach into every corner and touch every person in the institution. While the president leads the institution to accomplish its mission, the CFO is charged by the president and the board with supporting the institution’s mission by judiciously allocating its scarce financial resources[1]. This charge expresses a duty that the CFO is responsible for assuring that funds are used for their intended purpose as designated by donors, or as required by governmental regulations, or as directed by the board of trustees. The CFO also has a fiduciary duty to maintain the integrity of the institution’s financial resources so that current and future generations of students can attain the benefits promised in the mission statement. Due to the CFOs’ fiduciary duty and certain governmental regulations, he/she may be held responsible for any wrongdoing in how government funds are expended or reported.

The CFO is seen by some as a miracle worker, who has secret treasures where money can be brought forth to save the college. Others see this person during a financial crisis as the expert who can explain exactly what happened as though it was his/her decisions that led to the crisis. Then there is the deep wonderment of colleagues who see accounting as an arcane science designed to confuse laypersons, which in turn makes the CFO a high priest of financial magic. Obviously, these are flawed conceptions of the position of the chief financial officer. Nevertheless, “… there is a real values tension between the business function, with its emphasis on pragmatic accountability, and the academic function, with its emphasis on knowing, teaching, and learning[; ]… the CFO must learn to manage this dynamic tension…[to perform her/his duties] [2] . As will be seen throughout this blog, CFOs have a significant role with the board of trustees, president, the academic community, and other chief administrative officers in negotiating, allocating, administering, monitoring, and developing strategic plans and financial resources.

Readers will find that while the work of the CFO is arduous and has a jargon of its own, it is worth the time to learn how the chief financial officer works because it builds a common understanding of the possibilities and constraints of the institution’s financial capacity, which shapes strategic and management plans. This understanding is especially important when colleges and universities confront perilous financial times and as new challenges emerge from government regulations, demographics, technology, and the markets.

The significance of the chief financial officer’s position to an institution is also evident by the fact that regulators, lenders, and accreditors require that the monetary transactions and practices of the business office be audited annually. No other area (administrative or academic function) of a college or university has its decisions audited annually. When serious problems occur, a CFO often finds that the board, president, and others expect him/her to take responsibility for the failure and explain why it happened, even though the CFO may not have had authority or responsibility for the problem.

Annual audits and the burden of managing the financial resources of a college may explain why a CFO is sometimes seen as the designated “naysayer and grumpiest” person on campus. Yet many CFOs have a remarkable ability to say no and do it in a fashion that carries the respect of the campus community without eliciting recriminations or distrust. The latter are the paragon that all CFOs aspire to be.

As the preceding suggests, the CFO is not a trivial position given the range of decisions for which they have the authority to act, the responsibility to comply with statutes and regulations, and the task to carry out the mission of the institution. This chapter will briefly examine how a CFO supports the mission, strategy, and management of her/his institution, and why and how she/he seeks financial equilibrium.

CFO – Where They Work

The next two tables show the distribution of CFOs by type and size of colleges. It is interesting to note that when the distribution is by size, the order is from large institutions (greater than 2,000 students), to medium (between 1,000 and 2,000 students), to small (less than 1,000 students). When institutions are classified by degree levels of institution, the order of distribution for CFO is first at baccalaureate institutions, then doctoral institutions, and lastly at masters institutions.

Table I

Chief Financial Officers

Count by Degree Level and Size of College[3]

Table II

Chief Financial Officers

Distribution by Degree Level and Size of College[4]

The ordering by degree level and size is probably linked to the career path of most CFOs. It is probable that 61% of them will spend their careers in a baccalaureate college where the main financial issue is likely to be accounting for the flow of revenue from tuition revenue or endowments to expenditures and on to the assets or liabilities. For those who work at a small college, these CFOs will spend most of their career worrying about enrollment trends and student revenues.

CFOs working at large institutions, given the likely progression of responsibilities, probably started within the business operation of a large institution and moved up the ladder to CFO. This progression is valuable to the institution because the CFO learned business operations where tuition, endowments, gifts, grants, and investments are almost certainly several dimensions more complex than at a baccalaureate college. The trend in higher education is to apply the title chief business officer (CBO) rather than CFO. However, the title is not critical to understanding the work of the CFO/CBO. Nevertheless, as will be seen immediately below, the two titles are valued differently in terms of compensation.

If there is a difference in real economic value of CFOs among the different degree-level institutions, it should be reflected in compensation. Table III (source: College and University Personnel Association (CUPA)[5] suggests that chief business officers are more valuable than chief financial officers and that CBOs are more valuable if they are employed at a doctoral institution rather than at a master’s or bachelor’s college. One reason for the difference in values of the two positions is that the chief business officer has broader responsibilities than the chief financial officer as defined in the CUPA survey. A CBO, according to CUPA, has responsibility for financial and administrative functions, while a CFO has responsibility for the financial function[6]. If the relationship between economic value and complexity of work responsibilities are valid in the case of business or financial officials, then it would make sense that compensation would be greater at a doctoral institution. Chief business/financial officers at these institutions deal with multi-faceted revenue and expense flows that carry stringent regulations and require intricate operating systems to plan, manage, and monitor to assure efficient and correct receipt and use of funds.

Table III

Chief Financial Officers

Compensation[7]

While financial issues at large institutions are at a greater scale than other levels, it is not necessarily true that the problems of masters and baccalaureate institutions are easier to solve. In fact, the latter colleges may be tuition-driven and exist in a world of very limited resources where financial stability is uncertain and where long-term planning is secondary to yearly survival[8].

CFOs – Competencies, Characteristics, and Preparation

CFOs are one of the few chief administrative officers that do not come up the ranks of the faculty to achieve their position. They may come from auditing firms, accounting departments in public businesses, or business offices in other colleges. This path to the position of the CFO can be a source of conflict with the faculty and other administrators because the person holding the position is not familiar with the intricacies, conflicts, and traditions of academic governance. As a result, the CFO may be viewed as ill-suited to discuss matters of institutional strategy, academic budgets, and other items that do not directly concern the accounting function. In some instances, even their accounting responsibilities are under question within the realm of academia.

The CFO in most circumstances is expected to possess a very specific set of competencies. If they do not bring these competencies to their job, not only are they and their job at risk but so also is the college. This list of competencies covers these areas:

- General accounting practice

- Accounting and financial reporting

- Accounting rules from the Federal Accounting Standards Board (FASB) or Government Accounting Standards Board (GASB)

- Preparation and management of budgets

- Tax rules applicable to higher education and tax reports

- Supervision of business and financial office functions

- Procedures and practices of debt financing

- Oversight of investments.

The characteristics of a particular CFO will depend on the type and size of their corresponding institution. Commonly, the large private and public institutions expect their CFOs to be well-versed in their field and are to have broad work experience in business and financial offices within comparable institutions of higher education. Medium-sized private and public institutions may be the stepping stone toward a larger institution. However, the institution may still expect the CFO to have enough business office experience so that she/he understands the expectations and constraints that shape her/his business operations. Smaller institutions, because they often cannot afford the top dollar costs of CFOs with long experience in business management or in higher education, will take larger risks than large- or medium-sized institutions and will hire a CFO with little experience or one just out of auditing practice.

The background of a CFO usually follows a familiar pattern – bachelor’s degree in accounting, maybe a master’s degree in business or accounting, and a Certified Public Accountant (CPA) license. These particular educational experiences for the CFO are not fancy wrapping but are essential to doing their work. Their educational training can be long (up to five years) and expensive, all before they can even sit for the CPA examination. A future CFO’s first job is usually low-paying and is in an auditing firm or a business office, as time in these types of jobs is typically required to earn a CPA license

CFO Job Description – Just What Do They Do?

CFOs in most institutions have authority and responsibility over accounting systems, budgets, budget controls, purchasing, cash management, debt management, internal and external financial reporting, tax reports, and financial analysis[10]. In some instances, they may be in charge of investments, or, if not directly in charge, they at least have the duty to accurately record investment transactions. A CFO is also an advisor to the president, board, and other chief administrative officers on financial strategy and budgets and the impact of revenue and expense decisions on short- and long-term financial viability.

The basic function of the CFO is to manage every financial transaction of the institution no matter the size, which is circumscribed by the chart of accounts, internal standards, practices, and policies, and by the budget structure, which is then subject to Generally Accepted Accounting Practices (GAAP). It is the resulting flow from transactions that either expand or deplete the financial resources of the institution.

Transactional records provide the infrastructure on which the financial statements, financial management, and financial strategies rest. When transactions are consistently and accurately recorded, financial reports will reliably reflect the current financial condition of the institution, both its weaknesses and its strengths. Financial reports are critically important to the president, board of trustees, and chief administrative officers because these reports underpin financial decisions related to long-term strategies and operational plans. Accurate and reliable financial records and reports are the very essence of the work of a CFO.

CFOs – Why They Are Held Accountable?

CFOs are held responsible for their decisions by tough accounting standards, by regulations, and by the expectations and oversight of the board of trustees and presidents. Accountability is established through annual audits by a neutral third party, i.e., a certified public accountant (CPA), who conducts a rigorous review based on GAAP principles of financial transactions, decisions, and reports. The purpose of accountability is to assure users of financial data (such as boards of trustees, presidents, banks, debt holders, government agencies, and accrediting commissions) that the data are reliable, are accurate, and are in compliance with accounting standards.

The reason for harsh sanctions and for rigorous monitoring of the financial operation is that the CFO has the sole responsibility for maintaining the financial resources of the institution given that the board and other chief administrators have made prudent and reasonable plans to employ those resources. The CFO’s singular duty is to husband the scarce financial reserves of the institution to finance the survival, reputation, and quality of the institution for current students, for future generations of students, and for the alumni. If not caught in time, reckless inept, or misfeasance in financial operations can devastate an institution’s financial reserves that may have taken decades to accumulate and could take decades to rebuild.

Two simple anecdotes will suffice to show what happens when a CFO has the misfortune of making a glaring and costly error or when a CFO, working with the president, has the perspicacity to solve a historically-knotty financial problem. The first case will show how a CFO vainly tried to grow the endowment using a risky investment strategy. The second case is about a college where deficits slowly burned away its financial reserves, and the college was rebuilt through the wisdom of a new CFO and a new President.

The first case involves a small college where the CFO had responsibility for investing the college’s endowment funds. In 2000, when the technology bubble was expanding geometrically, the CFO placed the college’s endowment in a high-flying technology mutual fund. She/he made a classic mistake made by naïve investors – she/he bought high and sold low – very low. Within one year, the mutual fund lost 80% of its value, effectively wiping out the endowment. An annual audit might have caught this problem, but the error played out within a single fiscal year.

The second story relates how a new CFO discovered that the previous CFO and president had masked deficits for many years while consuming its cash reserves. The board of trustees had abrogated their fiduciary responsibilities and had accepted financial reports that had created an illusion of financial stability. The CFO and the new president had the unwelcome task of telling the board that the wonderland world of finance was untrue and that the college was near financial collapse.

The CFO and the new president realized that they had to quickly put into place a financial strategy which would quickly end the college’s long history of deficits. The first year of the new financial strategy explicitly forecast a deficit, but the plan was based on new enrollment strategies, expense cuts, and budget controls. Within five years, their efforts were rewarded because the college rebuilt its cash reserves, which permitted the college to begin renovating its infrastructure and investing in existing and new academic programs.

The first tale is a horror story, while the second seems too good to be true. However, happily for most colleges, the second story is typical of the contribution that a good CFO, working closely with the president, can make to restore financial viability by providing financial resources so that the president can implement his/her vision of how to turn the college’s mission into reality.

CFO’s Contribution to Mission, Strategy, and Management

Good colleges and universities use the mission as a compass that guides strategy and management within the constraints of their financial resources. This guiding principle requires good CFOs, who assist the president, board of trustees, and chief administrators in finding the right application of financial resources in order to achieve the mission of the institution. The right direction in financial management requires the right balance between expanding and using financial resources to develop and produce credible educational programs that serve the college’s mission but do not deplete its financial reserves. Getting direction and balance right requires a CFO who has the financial, management, and personal skills to support a college to provide the right services to enhance the lives of its students without sapping its strength with petty rules and demands.

Expanded Role of CFOs

Most CFOs do more than sit at their desk like Dicken’s Bob Marley in a green eyeshade with quill in hand noting dollars in foot-high ledger books. Of course, this statement is an exaggerated description of the modern CFO, who usually is responsible for more than finance. The typical CFO is titled as Vice President for Administration (VPA), which takes in finance, building and grounds, auxiliary services, outsourced services, security, human resources, and whatever else the president and/or board of trustees assign to them. The degree of aggregation of the CFO’s responsibilities is usually related to the size of the institution and historical nature of the function at the institution.

When a CFO is also a VPA, their workload may divert them from their main task of financial strategy and management[13]. The result is that in some cases the main job – finance – is given short shrift or squeezed while problems are addressed in residence halls, dining halls, security incidents, maintenance problems, and contractual issues. It is an especially gifted person who can take on the duties of a CFO cum VPA. That is why colleges and universities, when replacing a CFO/VPA, should pay for the best. Buying cheap is a false economy because lackluster leaders can have long learning curves resulting in a delay in introducing change or making sure that financial management stays on course.

The premise of paying for the best CFO also applies to staffing the business or financial office. While the college may save a few dollars hiring untrained people to do basic work in those offices, too often lack of training and ability leads to egregious and costly errors. Errors, when they are not eliminated and are large, may result in a loss of confidence in the business office and the reports that it produces. Credibility is a continuing and elementary prerequisite of every CFO and the business office that she/he supervises.

CFOs as Agents of Financial Equilibrium

The primary economic goal of the CFO is to find the point of equilibrium for the operational income flows of the institution given that its financial resources cannot remain static over time. The importance of this goal lies in the need for institutions to continually add income in response to inflation and to build reserves to maintain facilities and to respond to unforeseen events.

There is a misconception that not-for-profit colleges and universities operate under a zero net income constraint in which they can only generate enough revenue to cover their immediate expenses. If net income is zero, they would be like many small businesses that quickly fail because they are undercapitalized. Undercapitalization simply means that they would not have sufficient working or long-term capital to protect them against unexpected turns in the economy, changes in student markets, and tougher competition. Moreover, zero net income would continue to limit instructional efficiency to the size of the average classroom. A classroom of twenty to thirty students is not an efficient way of distributing the high costs of faculty. Colleges need to reach an equilibrium level where net income flows are large enough to maintain instructional operations while allowing for technological changes, higher demand for highly skilled workers, or shifts in demand by parents and students for comfortable habitation, athletic facilities, and other expensive amenities.

The main point is that equilibrium is not static but dynamic; changing in response to student demand, flow of gifts and income from endowments, internal costs, competition, financial markets, governmental regulation, accreditors, and other forces that dictate the financial condition of an institution. Dynamic equilibrium suggests that the CFO will not find a single point in which growth of costs cease, financial resources stay vibrant, and external forces have no impact on the institution. Given the fallacy of this premise, a CFO must seek an equilibrium strategy that dynamically responds to continuous changes from internal and external economic and financial forces that wreak havoc with the status quo. Developing and managing an equilibrium strategy is the most difficult challenge faced by most CFOs because they must work closely with the president to convince the board of trustees of the importance of reaching a state of equilibrium. Then, the CFO and the president must work with all sectors of the institution to develop and follow-through on a feasible and dynamic equilibrium strategy. Equilibrium will be discussed in further detail in a later chapter.

Final Comment

The chief financial officer’s position cannot be fully described within the limits of this blog because the importance of a CFO for a particular institution depends upon the characteristics of the institution, its unique place in the market for higher education, and the full set of responsibilities assigned to the position. As noted earlier in this blog, in many instances, the CFO is more than a finance officer; she/he may also have responsibilities for building and grounds, auxiliaries, security, parking, copying and printing, and whatever else others either do not want to do or a president feels that the CFO is best fitted to do. Nevertheless, you will find in the balance of this blog a nicely drawn picture of the work of the typical chief financial officer as it pertains to the finances of an institution of higher education.

Endnotes

-

West, Richard P. (2001); The Role of the Chief Financial and Business Officer; College University Business Administration; National Association of College and University Business Officials; Washington, DC; p. 1 ↑

-

West, Richard P. (2001); The Role of the Chief Financial and Business Officer; College University Business Administration; National Association of College and University Business Officials; Washington, DC; p. 2 ↑

-

Minter, John (2010) Private CFO.xlsx; John Minter Associates; Oregon ↑

-

Minter, John (2010) Private CFO.xlsx; John Minter Associates; Oregon ↑

-

2009-10 CUPA – HR Administrative Compensation Survey; Unweighted Median Salary by Carnegie Classification; CUPA – HR Surveys; College and University Professional Association for Human Resource Resources; Knoxville, TN; (May 14, 2010); http://www.cupahr.org/surveys/adcomp_surveydata10.asp ↑

-

2009-10 Administrative Compensation Positions; CUPA – HR Administrative Compensation Survey; College and University Professional Association for Human Resource Resources; Knoxville, TN; (Retrieved May 14, 2010); http://www.cupahr.org/surveys/participate.asp ↑

-

2009-10 CUPA – HR Administrative Compensation Survey; Unweighted Median Salary by Carnegie Classification; CUPA – HR Surveys; College and University Professional Association for Human Resource Resources; Knoxville, TN; (Retrieved May 14, 2010); http://www.cupahr.org/surveys/adcomp_surveydata10.asp ↑

-

Townsley, Michael (1991) Brinksmanship, Planning, Smoke and Mirrors; Planning for Higher Education; 19(4): pp. 27–32. ↑

-

West, Richard P. (2001); The Role of the Chief Financial and Business Officer; College University Business Administration; National Association of College and University Business Officials; Washington, DC; pp. 10-14 ↑

-

West, Richard P. (2001); The Role of the Chief Financial and Business Officer; College University Business Administration; National Association of College and University Business Officials; Washington, DC; p. 17 ↑