by Michael K. Townsley | Mar 7, 2026 | Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis

Slender Thread – 1

FTE Enrollment Trend from 2018 to 2024

The Slender Thread refers to the sources of financial resources needed by private colleges and universities to survive the upcoming demographic cliff. There will be five Slender Threads in this series. The order is: 1 – Enrollment Trends, 2 – Relationship of Tuition Discounts to Enrollment, 3 – Effect of Changes in Enrollment on Unrestricted Funds, 4 – Change in Total Net Assets, and 5 – Basic Survival Rules for Slender Threads.

This study used IPEDs data from 2017 to 2024 to compute the enrollment to unrestricted net asset ratio for 944 private colleges. This set of colleges was split into two enrollment groups: FTE < 1,000 students and FTE >= 1,0000 students. The data was then averaged for the two groups for each variable by year. The first chart has the basic data trend for both sets of private colleges, and the next two charts show the linear and a second-degree polynomial trend, i.e., a quadratic equation.

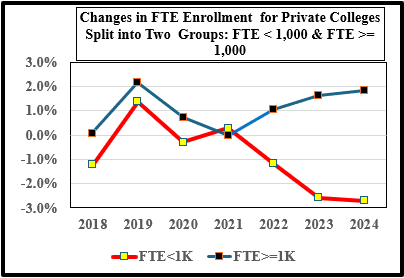

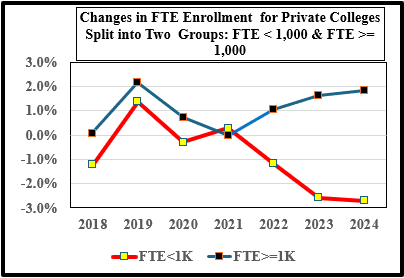

Slender – 1 covers the change in FTE enrollment for a set of 944 private colleges that are split into two FTE enrollment groups: FTE < 1000 and FTE >= 1,000. Changes in FTE enrollment is a critical factor for most private institutions because most of their revenue is generated from enrollment.

Chart 1 clearly shows that FTE enrollment in the small college group (FTE< 1,000) started to fall in 2016, then took a small jump in the latter stages of the COVID pandemic. After 2021, changes in FTE enrollment for small colleges resumed their steady decline through 2024 with a slight moderation of the rate between 2023 and 2024.

_______________________________

- The data set includes 44 private colleges from IPEDS for the period 2017 to 2024 that offered a four-year degree subject to these exclusions because they have different business models: seminaries, yeshivas, art and music schools, research colleges, and colleges with missing data. The last year for the data is 2024; This set of colleges was split into two enrollment groups: FTE < 1,000 students and FTE >= 1,000 students. The data was then averaged for the two groups for each variable by year. The first chart has the basic data trend for both sets of private colleges, and the next two charts show the linear and a second-degree polynomial trend, i.e., a quadratic equation. ↑

Chart 1

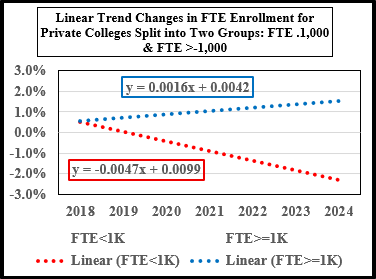

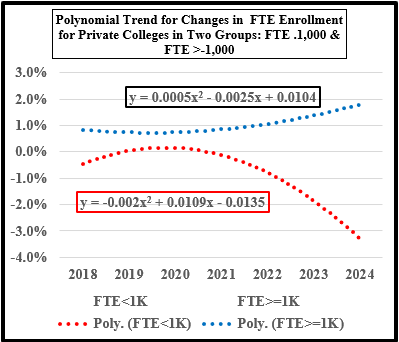

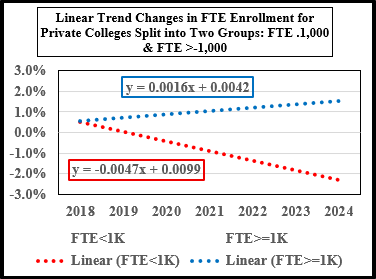

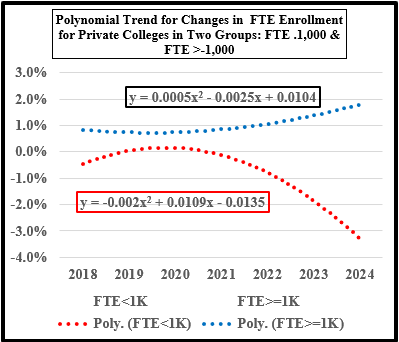

Charts 2 and 3 provide added support that small colleges have had a trying time stemming enrollment decline since 2018 except for the anomaly of 2021. It does not require a complicated analysis to suggest that small colleges will face tremendous pressure to keep their head above water during the impending demographic cliff after 2026. These three enrollment charts clearly show that delaying strategic change could doom the college given that most small colleges are heavily dependent on tuition revenue to survive.

Chart 2

Chart 3

Editorial Assistance by Jack Corby, Vice-President of Stevens Strategy.

by Michael K. Townsley | Dec 17, 2025 | Essays and Commentaries

It is difficult to imagine the structure of a college in ten years. A decade could bring even greater change than the technological change taking place in the past few years. In particular, there is a strong possibility that artificial intelligence (AI) will become more than a way for students to cheat on their classwork. AI may be on the cusp of dramatic changes in that may presage enormous changes in colleges and universities.

Changes in demographics, student preferences for majors and degrees, and the cost of operation will press higher education to change its operational model. Colleges in order to keep pace with student demand and control the price of tuition will be forced to restructure their instructional delivery systems, manage the administration, eliminate buildings, and sell of large segments of campuses.

Here is my take on how college could look in a decade. You can take this with a grain of salt, or as a piece of science fiction, but the dynamics of AI are so powerful that it is hard to imagine what it will do institutions and to higher education, in particular. The purpose of this paper is a thought piece about one scenario that might happen to a private college or university.

At the end of the paper, there is another brief of what higher education could like in 2035. This brief, Chronos, was designed by John Stevens of Stevens Strategy. It offers a model which combines an interpersonal approach with technology to higher education.

Artificial Intelligence Will Operate with These Components – Instruction, Academic Administration, Student Support Services, Marketing and Recruitment, Presidential Administration, Finance, and the Plant.

Operational Structure- the college would be managed from sub-systems that flow into the central management system. The system will operate through the previously listed components based on the following principles:

Component Sub-System Design:

- Goals of the sub-system is to efficiently and effectively deliver the services for that component;

- Component design objective – to include all the factors need to efficiently and effectively: move students through the sub-system or provide operational support for students, or maintain continuous operation of technological services and maintenance of the plant.

- Each sub-system will have a manager, who is responsible for the efficient and effective daily operation of the system;

- The sub-systems manager will have following staff with ratios adjusted with experience:

- Instruction – ratio of 1 staff per X students; suggest a ratio of 1/150 students;

- Academic Administration – ratio of 1 staff member per X majors with other staff in relation to other sub-system reports; note the library services will primarily be conducted on-line;

- Student Support Services – ratio of 1 staff member per x students; suggest a ratio of 1/250 students; note, since there will be few if any dorms or major activities, this sub-system will not need many supporting staff;

- Marketing and Recruiting – ratio of 1/budgeted new students; suggest a ratio of 1/50 new students; not this ratio will depend on whether the college continues to conduct traditional recruiting drives;

- Presidential Administration – ratio of 1 per Key System Managers and additional staff as needed to perform the duties of the president;

- Maintenance of the Plant; this sub-system will need a complement of skilled workers to maintain the plant; other duties such as lawn work, janitorial work is will be contracted to third parties, the Maintenance of the Plant manager should be able to handle direct supervision of third-party services;

- The management principle for sub-systems – management by exception by identifying errors and problems that can be immediately fixed; system manager will take responsibility for long-term problems;

- The manager will have a minimum number of technologists or support staff with skills needed to deliver on the goal(s) of the sub-system.

- The sub-system will regularly report to the appropriate system managers on performance, long-term problems, and recommendations for design changes.

System Managers:

- Each component or a combination of components will have a system manager responsible for strategic management, operational oversight of sub-system performance, and resolving major errors or problems with the system.

- Technology Managers,

- There will an IT software and hardware technology manager, a communication system manager, and an AI system manager;

- Each technology manager will be responsible for maintaining daily operations, updating systems, and designing processes to correct errors and faults;

- Each manager will meet regularly with sub-system managers and sub-system technology support staff.

- The technology managers are responsible for the security and integrity of their systems.

- System managers will conduct regular meeting to review performance, identify major problems, recommend changes in design or system procedures, and propose strategic changes to improve efficiency and effectiveness of the system

Key System Managers:

- Chief Operating Officer (COO) is responsible for managing key system managers and the efficient and effective operation of the system. They will be like mission control of moon missions; receiving continuous report on operational data, chairing regular system manager meetings, and preparing long-term operational st

- Academic, Marketing and Recruitment, Finance, and Plant;

- Key System Managers:

- Regularly meet with the president to report on sub-system performance goals, problems, and the need for special expenditures;

- Academic systems manager conducts regular oversight meeting with sub-system managers, identifies major issues that are adversely affecting student performance or completion of a degree. Also, the academic system manager is responsible for assessment of student, and graduate performance standards.

- The marketing system manager will provide on-going performance reports, major issues that are adversely affecting enrollment, competitive conditions, and strategic plans.

- The finance system manager will provide daily and weekly reports on cash flow, student payments, net budget performance, estimated end-of-year net and cash flow; status of bond covenants, and any financial system problems that need technical staff to correct.

- Plant system manager is responsible for plant operations, repairs, and long-term infrastructure needs that have to be resolved to assure efficient and effective operation of the plant systems. The plant manager is also responsible for on-campus security, electrical back-up, and minimizing the chance of electrical faults due to lightening, unexpected surges, and blackouts.

President

The president as the leader of the institution, the solicitor of donations, and the chief strategist of the college oversees all the work of the systems. However, the president does not participate in the daily oversight of the system that is left to Chief Operating Officer. Here are several critical roles that the president does play regarding the operation of the system:

- The president is responsible for achieving efficient and effective performance regarding the operations of the institution.

- Chair of the monthly and end of academic period review with the chief operating officer and key system managers; the goal of the meeting is to identify any changes in college policy or procedures that require the approval of the president.

- The president is responsible for resolving issues between the chief operating officer or the key system managers, or the sub-system managers which have become an obstacle to on-going operations.

- The president as chief institutional strategist will chair budget and strategy meetings with the chief operations officer, and key system.

- The president has the direct authority of the board of trustees for management of the institution; furthermore, the president meets with board to conduct business regarding operational performance, policy changes, and the financial condition of the institution; anyone seeking to meet with the board of trustees will need the authorization of the president.

- The primary relationship of the auditors is through the president as delegated by the board subject to the auditors reporting indignantly of the president.

Physical Location and Design of the AI Performance Tracking System

- Operational Headquarters that includes the offices of the president, chief operating officer, Key System Managers, and Sub-System Managers except for the Plant Operation Manager, and house the AI and IT systems with generating capacity next to the building, and physical mail reception station.

- Plant Systems will be in a separate building and will house central utilities, security, custodial services, emergency tools and equipment, maintenance and landscaping equipment, and campus generator back-up to the Operational Headquarter generator,

- Parking will be adjacent to Operational Headquarters and the plant operations building.

- Classroom building will include sufficient space for all classrooms with backup technology services, backup generator, and storage for supplies.

- System Display Boards Location

- The master display would be in the operational headquarters building. The room will be large enough to accommodate the full board, the COO in a large office that overlooks the master display board, and sufficient cubicles for key system managers.

- Sub-System managers will be in separate rooms on other floors with direct connection to the COO.

Benefits of the AI Management System

- Helps students with the potential to lower tuition prices due to lower costs per student;

- Gives students more precise tutorial assistances to support their course work;

- Concentrates management in one location;

- Provides continuous and real-time access to student progress and plant operations;

- Identifies bottlenecks, errors, and other problems and prices this information to the level charged with managing operational issues.

- Affords central management problem solving for large operational issues that require changes in policies and procedures across the system.

- Offers a central location in the operations center to deal with unexpected emergencies or large-scale operational problems.

- Generates on-going and regular reports on goals and objectives of the college.

- Reduces the footprint of the college, which provides the board of trustees with the opportunity to sell off excess property and equipment and to use the sales income to pay down long-term debt.

- This system should increase the operational efficiency through constant monitoring of performance while reducing costs by eliminating redundant employees and disposing of unneeded buildings and equipment.

What Happens to Small, Financially Stressed Colleges That Can’t Adapt This Model?

Small colleges already face tremendous financial stress due to the enrollment cliff, changes in student preferences for majores, costs of operations, and internal resistance to change. There best option is to find a partner where both parties could have sufficient resources to make the lead to the high-technology college of 2035.

_______________________________________________________

Chronos Project

John Stevens, Stevens Strategy

Chronos:

Students want new model with interactive learning and individualized learning (not one size fits all), Yet, 75% of all entering college freshmen still desire a residential experience. 5.6 million students want cutting edge technology (e-learning), ten times more than those who want traditional instruction. The Chronos model offers 1000 percent growth in market for on-line learning

Chronos Summary

- Affordable, technologically delivered liberal arts and pre-professional;

- Individualized instruction with state-of-the-art technology;

- Integrates curricular, co-curricular and residential learning;

- Revolutionizes faculty work;

- Accredited degrees in 2.5 years;

- 45% of average student private college net price ($15,830*/$7,221 / sem.);

- 65% of average private college book price ($24,935*/$16,208/ per sem.);

- Campus – size is subject to existing campus;

- Predicted Net Profit: $116 million net profit annually at optimum enrollment of 5,000 students.

Chronos Model

- General Description

- Coaches organized by learning groups;

- Interdisciplinary programs and majors;

- Integrates curriculum and co-curriculum;

- Integrates living and learning;

- Individualized, technology-based instruction;

- Collaborative Project-based learning;

- Low tuition and fees;

- Accelerated graduation in 2 ½ years;

- Assessed by grades, projects, e-portfolio;

- Learning outcomes structured around 21stCentury career options.

- Continuous Student Assessment

- Pre- and post-testing of the expected learning outcomes associated with each course;

- Student’s performance assessed by grades in each course, Learning Coach assessment of participation in group projects and e-portfolios;

- Learning Coaches evaluated by aggregate student grades, pre- and post-testing of learning outcomes in courseware developed by each coach and 360˚ performance appraisals;

- Staff evaluated against benchmarks in their area of responsibility and 360˚performance appraisals.

- Key Financial Planning Elements

- Technology based delivery system;

- Learning coaches; coaches, assistant coaches;

- Lean administrative structure;

- Three trimester a year academic program;

- Efficient and green physical plant.

by Michael K. Townsley | Dec 13, 2025 | Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis

Private colleges in deep financial distress must be extremely adroit to survive. Specifically, presidents of these colleges will be forced to devise financial strategies that do not violate the law but will teeter on the edge of credible and acceptable actions by creditors, bankers, auditors, accreditors, and government officials.

Examples of the Slender Thread

- Auditors’ final report –

- Going Concern Issue, affects credit standing and capacity to borrow;

- Assets are reduced placing college in violation of debt covenants;

- Positive Net Change in Net Assets Revised to Negative Net Change placing college in violation of debt covenants;

- Indicates that the college has been borrowing from the endowment in excess of allowable amounts; placing the board of trustees at legal risk and the college at risk to pay back the excess;

- Indicates that the college has significant bookkeeping errors that raise questions about the validity of financial reports filed with lenders and regulatory agencies.

- Accreditors action –

- Rejects new program that was expected to produce sufficient revenue to cover future deficits;

- Rejects policy changes needed to cut academic costs;

- Places the college on warning notice.

- Government Regulatory action –

- Federal financial score for financial aid falls below minimum leading to the government requiring a substantial set aside of credit to be available to continue to receive federal aid. This could deplete cash reserves to the point that continuing operations is not possible.

- State regulator rejects a new program with a similar consequence as with accreditors rejection.

- Local government turns down zoning changes that would permit the construction of a new revenue generating building with similar consequences to the rejection of a program.

While these cases are hypothetical, many colleges have had to deal with them. In some instances, unexpected negative reports from an auditor, accreditor, and federal or state agency has pushed a college to the very edge of financial collapse.

The Slender Thread Can Bring a College to Its Knees

When It Snaps!

Go to Doors to Academia for More Posts on the

Current State of Higher Education

by Michael K. Townsley | Dec 13, 2025 | Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis

This paper addresses the factors that constrain a college president from constructing an efficient and effective system to achieve its mission. This paper aims to help presidents understand the factors that stymie operational strategies and plans, and how to mitigate these constraints to improve their chances of achieving the college’s mission.

According to Peter Drucker, a noted author on management, the purpose of a manager is to provide efficient and effective management in accomplishing the goals of an organization.[1] Efficiency in a college means that the process of producing a degree is at the lowest cost, as cost directly impacts tuition charges. Effective management involves choosing the best options to deliver an efficient outcome. O. E. Williamson, a noted economist of organizations, said that efficient and effective performance is not a simple task of pulling the right levers. According to him, organizations are inefficient and ineffective when common economic factors impede operational decisions.

In higher education, these obstacles are compounded by the inherent conflicts that flow from dual or shared governance of a college.

Factors Affecting Efficiency and Effectiveness in Private Colleges

- As O.E. Williamson, a distinguished author on organizational failure, has pointed out, a limited audit of academic and administrative programs can improve an effective process for the production of a service when those processes are regularly audited. In this case, he is not referring to financial audits but to audits of policies, procedures, and delivery systems.[2] The administrative systems, in particular, IT systems should be part of operational auditing because they control so much of the basic administrative work and the delivery of instructional services. Internal audits of academic and administrative performance are rare. Accreditation reviews are insufficient because they tend to be formulaic and fail to dig deeply into academic and operational performance.

One way to improve academic and operational efficiency is to conduct annual audits of both services that review in detail, policies, program designs, and operational performance. These audits should conclude with recommendations on how to improve efficiency and effectiveness for academic programs and IT services.

- Assessment of outcomes, like auditing of the delivery of services, is necessary to determine if the outcomes are the ones that a) the college intended to deliver, and b) the outcomes that graduates wanted. Too often the assessment of outcomes simply involves a count of graduates which can at least show the trend in graduates in absolute numbers or the trend in the percentage of graduates over time. This type of assessment does not get at the quality of the product, such as whether students are learning anything and whether they are building successful careers based on their academic experience. There are numerous ways to examine the question of quality, but written surveys may not be the best because they cannot question a graduate in depth about their degree. It seems that a better approach would be to interview random sets of students over time to get at their understanding of how college contributed to their lives or their success in their careers.

- Failure to estimate the cost per student or credit hour, and the cost of delivering a course, an academic program, or graduating a student. Deeply examining cost data requires that most business offices revise their chart of accounts, which are used to assign expenses. Too many charts excessively aggregate accounts. For instance, most charts do not precisely differentiate expenses between undergraduate versus graduate programs. It is the rare chart that even considers separating expenses by academic program, let alone by course.

The first level of a cost report should be the direct costs of delivering academic services to students, such as instruction, student services, and academic support. The next level of analysis is to estimate and apply administrative costs to direct costs. It is at this level where cost assignments become challenging. Revenue Cost Models (RCM) have worked with this problem for several decades. The difference between RCM and cost analysis is that the latter does not attempt to match revenue to expenses.

This data is critical if a college intends to manage its cost of operation. Since so few colleges have precision charts, it makes it difficult for a college to compare its costs with its competitors. As a result, the assessment of detailed costs must depend on the good judgment and experience of the president and the other chief administrators.

There are several requirements for establishing a cost estimation analysis:

- Precisely define costs and assign the costs to the units generating costs;

- Redesign the chart of accounts directly to the unit that generates revenue and expenses transactions;

- Set-up IT reports to regularly generate detailed cost/unit;

- Determine performance benchmarks. This aspect of the analysis may be the most difficult because cost analysis reports are not widely published. Several possibilities would be for a set of colleges to jointly produce cost reports to establish ranges. Of course, other colleges may not be too excited about having publicly disclosed reports of their inefficiency. Another possibility would be contract with a national auditor or a university with a higher education data analysis center to conduct cross institutional analysis.

- Too many colleges are slow to match the outcome of their programs with changes in the prospective student markets. As a result, colleges lose opportunities to increase enrollment or worse find that enrollment slips as prospective students look elsewhere for programs to provide them with marketable skills. Since the COVID pandemic and the onslaught of the demographic crash, many colleges are becoming more adept at responding to their prospective student markets. Regrettably, too many colleges have waited to take even elementary steps to change their programs or worse they stubbornly ignore that their prospective student market has changed what it wants from a college degree.

Dealing with matching the student market to a college’s programs and its outcomes is made more difficult because many presidents too often fail to:

- Listen to their external intelligence sources like, their admissions officer;

- Keep current with the market strategies of their competition;

- Read articles about how other colleges are able to match their prospective student market with their academic programs and outcomes.

- Organize a coherent marketing operation that regularly meets with the president about changes in the market and ways to respond to those changes.

- Have the vision to see academic or financial aid strategies that would be attractive to their market.

- Look beyond the immediate geographic boundaries of their current market.

- Hire the best consultants; too often colleges waste money on consultants who rehash their prior failures or worse do not spend the time to understand the unique character of a college’s marketplace.

- The use of monetary incentives in colleges is a sticky wicket, because they are contrary to the non-for-profit rule that profits cannot be distributed to employees.[3] However, many colleges have dodged this restriction with fancy legal footwork, but the issue remains a risk due to the college facing substantial tax issue, if the IRS rules that a bonus violates the non-distribution rule.

Because colleges generally avoid broad stroke incentives for lower-level employees in its organization, they have a difficult time targeting employees or groups to improve performance. In addition, incentives to individuals, even when it does not take a monetary form, can upset the culture because team members may look on the incentive as an undesirable change of status for a member or unwanted pressure on the team or other teams. This can often result in resistance leading to counterproductive results, such as; a lowering rather than increasing productivity.

There are alternatives to singling out a single person for an incentive, for example, incentives for team, or benefit for groups involved in a certain tasks like admissions, registration, and student advisement. Presidents who want to provide incentives to improve efficiency and effectiveness need to carefully design incentives to avoid unexpected consequences.

Dysfunctional decision-making often takes place at the interface between the administrative hierarchy and the faculty senate, which represents faculty peers. Cohen and March described the problem of leadership, where the leadership side is weak and the faculty side is strong as being enmeshed in ambiguous internal forces that confound rational decision-making.[4] Ambiguity of leadership describes why college presidents are unable to optimize decision-making but depend on arbitrary events to hopefully maneuver toward a productive decision. Although the ‘ambiguity of leadership’ paradigm superficially describes decision-making, it leads to piecemeal solutions and not coherent strategic action. Regrettably, the split between presidential leadership and faculty governance is an indicator of inefficiency and ineffectiveness in achieving its mission and serving its students. Unfortunately, leadership game playing leads to substantial delays or lost opportunities to improve efficiency and effectiveness.

Cohen and March’s paradigm suggests that ambiguity at the interface between the hierarchy and the faculty senate often forces the president into becoming a game manager who must become adept at waiting for infrequent opportunities to shape academic change.[5] This game even has a rule book – the faculty handbook – which is commonly written by the faculty, whose interest it directly serves.

Under these circumstances, presidents are unable to respond effectively to small changes in the market or student markets, governmental regulations could damage the fiscal integrity of the college in the long-run. There is a philosophic term for this condition, it is called ‘creeping normalcy’ where supposedly small problems are ignored, opportunities are lost, and eventually an institution falls into a state of

As a final note about the organizational failure that is evident in the interface between the presidential hierarch and the faculty peer group will depend on the following:

- Gifted college presidents who have the skills and personal strengths to convince the faculty that academic change serves their long-term interests and the college’s.

- A series of crises that forces leadership and faculty to leapfrog any ongoing conflict between the two governance forms. For example, it is apparent that the continuing crisis caused by the demographic cliff, COVID, or changes in student preferences for degrees is forcing a lowering of the conflict boundaries between the faculty and the president.

- Further resolution of this organizational failure will have to wait for accreditors and regulators permit colleges to determine if the dual governance structure in higher education continues to have value in the governance of colleges.

Go to Doors to Academia for More Posts on the

Current State of Higher Education

ENDNOTES

-

Drucker, Peter (1973); Management Tasks. Responsibilities. Practices; Harper; New York; pp. 47-48. ↑

-

Williamson, Oliver (1975); Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications; The Free Press, Division of Macmillan Publishing Col; New York; pp. 146-147. ↑

-

Gibbons, Robert and John Roberts, editors (2013); The Handbooks of Organizational Economics; “Ownership and Organizational Form”; Harry Hansmann; Princeton University Press; Princeton; p. 908. ↑

-

Michael Cohen and James March (1974); Leadership and Ambiguity; Harvard Business School Press; Boston; pp. 199-229. ↑

-

Ibid; pp. 199-229. ↑

by Michael K. Townsley | Dec 13, 2025 | Essays and Commentaries

Processes vs Outcome

Accreditors tend to be descriptive, prescriptive, and proscriptive, but to really get at these two basic issues:

- Do graduates have the skills to find and hold a job

- Does the institution have the resources to sustain its mission.

Before we delve into these questions, let us look at standards from two accreditation commissions: Middle States Committee on Higher Education (MSCHE) and The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools Commission on Colleges (SACSCOC). These two commissions were selected as typical of all commissions even though others may differ in minor ways. The following table identifies similar standards for each commission.

Table 1

Comparison of Standards for MSCHE and SACSCOC

| |

|

MSCHE

|

SACSCOC

|

|

1

|

Mission

|

X

|

X

|

|

2

|

Ethics

|

X

|

|

|

3

|

Design & Delivery of Instruction

|

X

|

|

|

4

|

Library & Learning/ Information Resources

|

|

X

|

|

5

|

Educational Program & Structure

|

|

X

|

|

6

|

Educational Policies, Procedures, &Practices

|

|

X

|

|

7

|

Outcomes

|

X

|

X

|

|

8

|

Faculty

|

|

X

|

|

9

|

Student Support Services

|

|

X

|

|

10

|

Financial & Physical Resources

|

|

X

|

|

11

|

Plans & Goals

|

X

|

X

|

|

12

|

Transparency & Institutional Representation

|

|

X

|

|

13

|

Governance & Administration

|

X

|

|

|

14

|

Governing Board

|

|

X

|

While these two commissions may set-out the standards in different groupings, in the end, they are both going after the same type of information. They both are looking for: authority for their existence, evidence of planning and control of instruction, information showing strategic planning, documentation of governance mechanisms including shared governance between academic program and the president and the board of trustees.

The work involved in collecting data, writing reports, committee meetings, reviews, putting together the final document, and preparing staff, faculty, administration, and the board of trustees can run into a hundred thousand hours of work during the year of the accreditation visit. Yet, preparing data and draft reports for the visit can take several years. In addition, the reports for academic and instructional departments may take a disproportional amount of time to complete.

However, it is worth questioning whether today’s accreditation process truly serve the interests of the government, who provide a substantial, if not most of the funds, for most colleges and universities and does it serve the interests of the students who enter the institution to gain skills that will serve their financial needs in the future. I suggest that the current certification system is too process oriented, time consuming, and needs to be redesigned to respond to two essential questions – can students find ‘gainful employment’[1] after graduation and does the institution have sufficient resources to serve its mission, support current operations, and provide sufficient assets for future students. Here is how I would suggest restructuring the certification process:

- Legitimacy – Collect data on the current governmental authority and incorporation documentation of the legitimacy of the institution to operate.

- Annual Financial Condition– Provide three years of audits and management letters to attest to the financial condition of the college.

- Legal Liabilities -Provide information from the college’s legal counsel about outstanding legal actions against the college or its employees.

- Strategic Financial Condition -Use Richard Cyert’[2]s model of economic equilibrium to estimate if the institution has sufficient resources to accomplish its mission, both now and in the future. His concept of equilibrium asks these two questions:

- Does the institution have sufficient quality and quantity of resources to fulfill the mission of an institution?

- Does the organization maintain: the purchasing power of its financial assets and facilities in satisfactory condition.

- Cyert’s equilibrium model is not difficult to compute and universities have data available in their audits.

- Graduate Employment – Collect data on the gainful employment of graduates over a fixed time period Although this requirement has not yet been approved by the government to determine if a college is to receive funding, it is significant information that the college needs and students need to determine the value of a degree.

- Graduate Proceeding to Graduate/Professional Schools – Collect data on graduates who apply to graduate or professional schools to determine if they were accepted. This standard is not part of a proposed federal student funding decision, it is relevant to the college and to students intending to get either a graduate or professional degree. If a college is counseling students with the intention of earning a post-baccalaureate intention, the college and these students need to know how successful graduate are at earning the next degree.

- Graduate Skills Analysis – Collect data on the skills of graduating students compared to entering students, to comparable institutions, and to curricula identified skills. This standard is directly pointed out at the real question about going to college. Do the skills of its graduates achieve the skills defined in the curricula and are their skills greater than the skills when they entered college.

These seven revised accreditation standards would replace the fourteen steps currently used by most accreditation commissions. There is a possibility that the revised accreditation steps would require less time and resources than the current methods. The greatest challenge for colleges under the new system would be the challenge of collecting data on gainful employment. However, if the federal government eventually moves to this standard in its own consideration of funding for higher education, colleges will need to come to grips with data collection. It would not be too surprising to find third-party data analysts take on data collection and reports for the gainful employment standard.

Summary Argument – I would argue that if graduates have gainful employment, the acquired skills listed in the curriculum, and there are sufficient resources, then these outcomes speak for the validity of the processes.

Go to Doors to Academia for More Posts on the

Current State of Higher Education

NB: Editing assistance by

- James Gaddy, Vice-President for Advancement; Albright College

- Jack Corby, Vice-President; Stevens Strategy

Footnotes

-

. Gainful employment would follow the basic rules of the government that essential asks if a graduate can find employment that provides sufficient financial resources for their life, family, and future. It is not a happy phrase for many in higher education because of the difficulty of collecting the data, but it does get at one of the essential issues of the existence of a college, does it serve the future economic conditions of students given their cost of investment in a degree. ↑

-

. Richard M. Cyert was President of Carnegie-Mellon University, a noted economist, statistician, and author with James Marchof the seminal work on organizations – A Behavioral Theory of the Firm. ↑