by Michael K. Townsley | Apr 6, 2024 | Financial Strategy and Operations, Private Colleges & Universities in Crisis

Michael Townsley, Ph.D.

March 31, 2024

Introduction

For the past decade, our colleagues and columnists have remorsefully muttered about friends in terminally ill colleges. Now, we know “for whom the bell tolls.” As more old colleges are thrown on the death cart, other small colleges only wait and wonder if their college is next to be chucked on the heap of history.

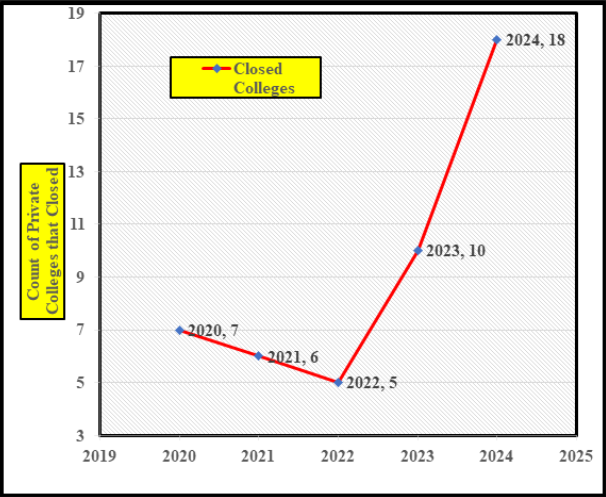

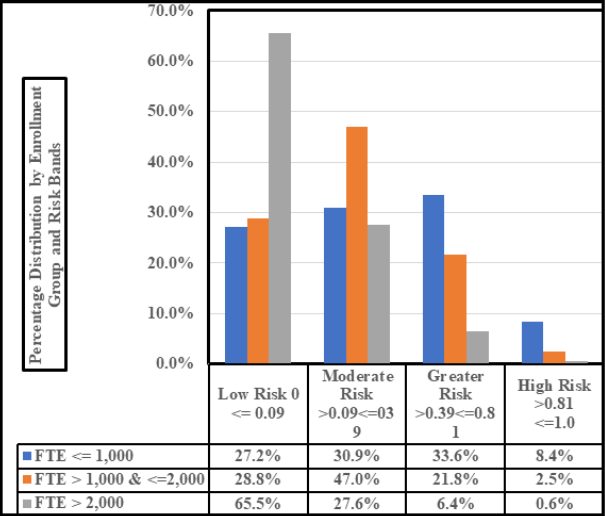

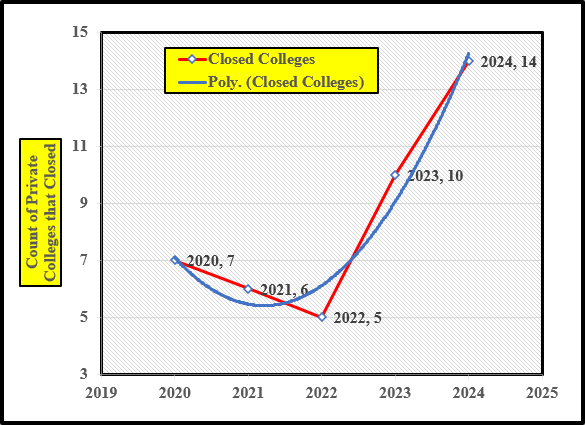

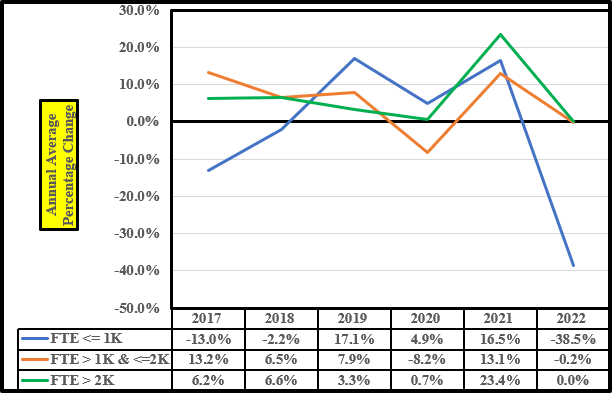

College closings have accelerated since 2022 despite the large influx of federal funds in 2022 (see Chart 1). What is particularly troubling for 2024 is eighteen colleges have announced that they are closing or closed in just the first three months. This is twice the average for the previous four years. If that trend continues, seventy-two private colleges could close by December 2024.

Chart 1[1]

Count of Private Colleges and Universities that Closed between 2020 and March 2024

Seemingly, COVID funding may have masked financial problems that reappeared as the funds were depleted. Here are several problems, given current conditions in the private higher education market that could have an adverse effect on the financial vulnerability of a college:

- Long-term decline in births and by extension smaller high school graduation classes.

- There is no single demographic on the horizon that can provide a large number of new students as there were starting in the 1980s, when women either returned to finish a degree or working women saw opportunities that a degree would provide.

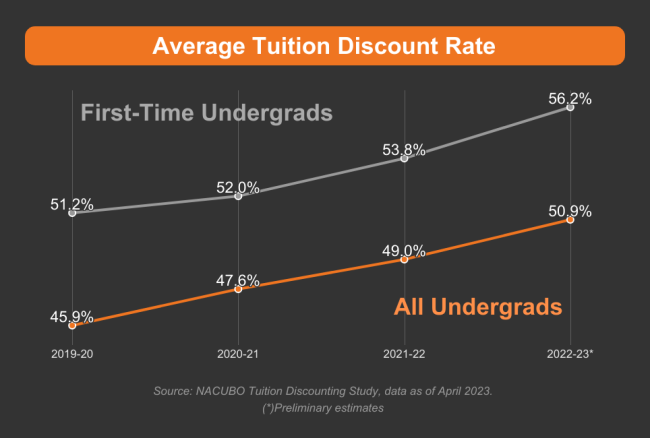

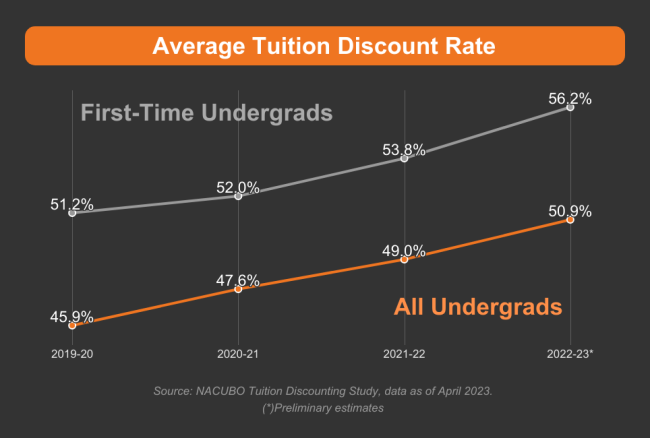

- When the pool of buyers shrinks, economics posit that prices will decline and either demand will increase or supply will decline, thus colleges will close. Prices, in this case tuition, are cut by increasing the tuition-discount rate. NACUBO (National Association of College and University Business Officials) reported that in 2023 the discount rate was 56.2%.[2] As discounts rise, tuition produces less cash, which reduces the amount available for expenses. Tuition discount increases coupled with less cash from tuition is worrisome for tuition-dependent colleges and universities. Because the average discount rate was 56.2% in 2023, the average private college received ess than 50 cents on the dollar from tuition revenue. Several news items note several colleges are offering discounts up to 65% of tuition (this rate does not include discount rates offered by highly selective colleges and universities).[3]

- Some colleges continue to retain academic programs with too few students and too many faculty and staff, while other colleges are eliminating programs to reduce costs. (See this reference: “How US Colleges Are Responding to Declining Enrollment”.[4]

- Colleges are expected by governmental regulators to moderate rates of attrition, Therefore, low academic skills of entering students force colleges to expand academic support services at significant cost to minimize attrition. (See these references for articles about skill: “Student achievement gaps and the pandemic”[5]; “The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning”[6]; “Math Skills Fell in Nearly Every State”[7] “High School Students Think that They are Ready for College, But They Aren’t”[8]

- Owing to declining enrollment, some colleges carry empty rooms and buildings on their books Although these rooms and buildings are not used, they still drain resources as they need custodial care and regular maintenance, otherwise the unused building could become a safety hazard.

- Maintaining and operating out-of-date IT equipment and software reduces the capability of a college to serve its students, manage its finances, and efficiently run academic and administrative software. Since these colleges may not have the resources or the good fortune to receive grants or gifts for new IT technology, they will lag behind better-funded competition and be less attractive to new students.

Vulnerability Gauge – Predicting Financial Risk

This paper introduces a Vulnerability Gauge to predict if a private college or university is or is not at risk of financial failure. A logit regression tested the model with several different combination of variables. The model was applied to a random sample of forty-four private colleges and universities drawn from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS). database. The tests found the most robust and parsimonious model had an 86.3% prediction rate of financial risk when these two factors were used:

- Annual percentage change in unrestricted net assets over five-years (for most private colleges, these assets represent the ready financial reserves that cover operational expenses);

- The total change in FTE (full-time enrollment) over five-years.

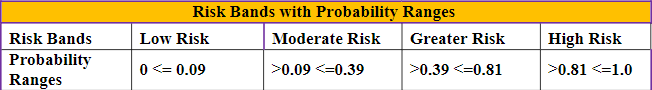

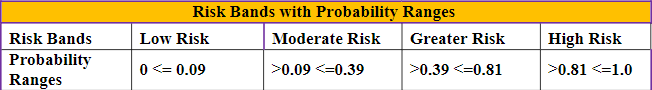

The logit regression yielded probability of financial failure for each school in the sample. The probabilities were then arrayed into four risk bands: low, moderate, greater, and high risk of financial failure as shown in Table 1. The risk bands indicate that the lower the probability, the lower the risk of closing and the higher the probability, the greater the risk of closing.

Table 1

Risk Bands of Probabilities for Study Sample

Findings from Large Sample Analysis of Unrestricted Net Assets and Enrollment

After the random sample was tested, the model was then employed to test the vulnerability of 949 private colleges that were open in 2016. This sample excluded medical schools, research institutes, arts programs, seminaries, and other specialty colleges. The analysis covered the period 2016-17 to 2021-22, which was the most recent year in which IPEDS higher education data was available.

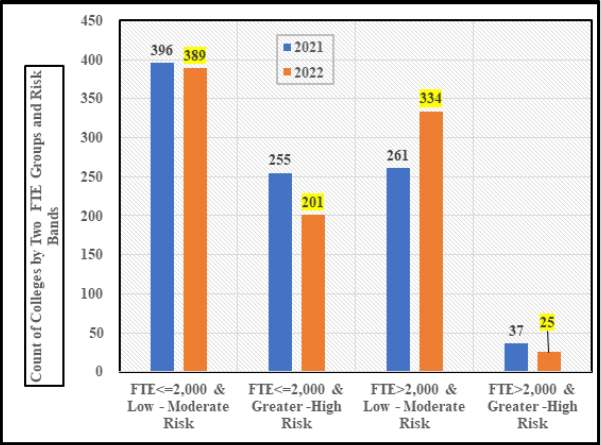

Chart 2

Colleges Assigned to Two Classes of Risk and Enrollment for 2021 and 2022

Chart 2 compares colleges based on their risk band and enrollment (FTE) for the years 2021 and 2022. Two major variables are displayed in the Chart – FTE enrollment and Risk Bands, which are described in Table 1. The FTE is divided into two categories of colleges, FTE with less than or equal to 2,000 students and FTE with more than 2,000. The second variable merges Risk Bands. The first risk band includes colleges with low to moderate Vulnerability Guage scores of ‘0 to less than 0.39’ and the second includes colleges with greater to high-risk scores greater than 0.39 to 1.0.

Here are several observations from Charts 2:

- In 2021, 255 private colleges with less than or equal to 2,000 students were rated at greater to high risk, but only 37 colleges with more than 2,000 students were rated with the same risk. In other words, institutional size seems to be a major factor in determining risk. In 2021, the risk rating for small colleges was 6.9 times greater than for larger colleges.

- In 2022, 201 more smaller colleges than larger rated as greater to high risk, 54 fewer colleges than in 2021. Yet, the greater to high-risk rating for smaller colleges was 8.0 times larger than larger colleges.

- In 2022, the enrollment group with more than 2,000 students saw seventy-three more colleges rated as low to moderate risk, in comparison to 2021, but this group had twelve fewer colleges rated as higher to greater risk.

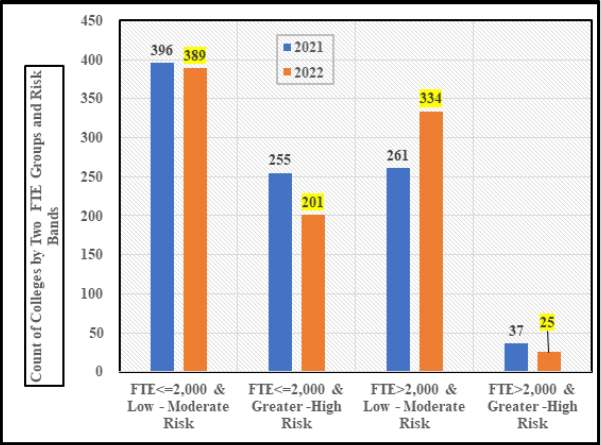

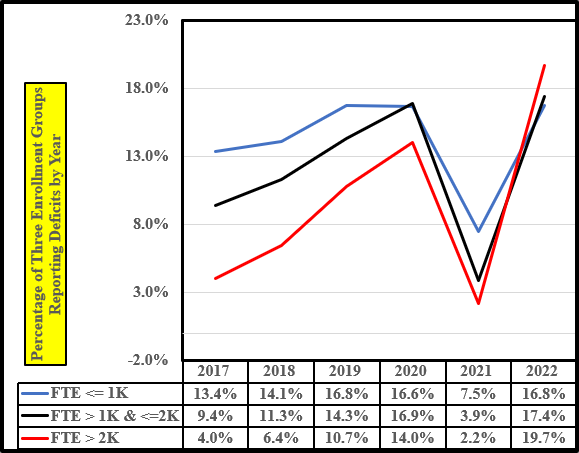

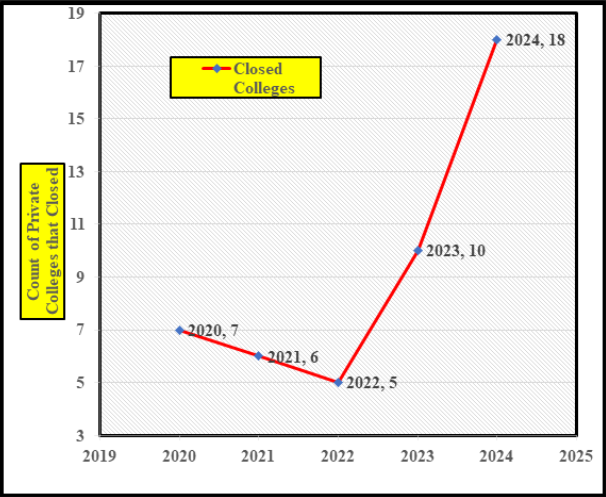

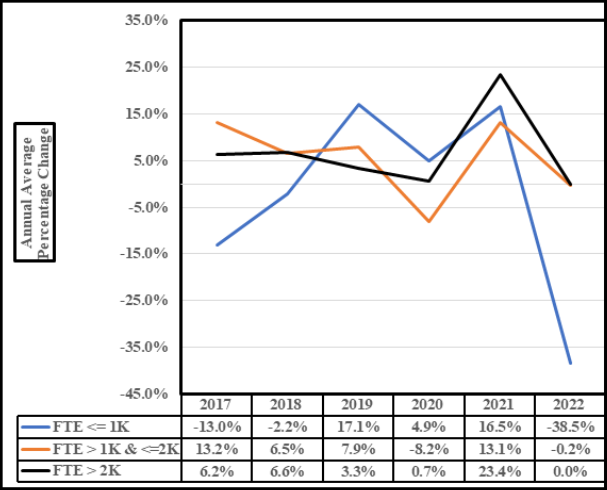

Chart 3 includes the same enrollment and risk groups as in Chart 2, but includes the average percentage change in unrestricted net assets for the years in the 2016-17 to 2021-22 period.

Chart 3

Average Percentage Change in Unrestricted Net Assets for Colleges Rated as Low, Moderate, and Greater Risk from 2016-17 to 2021-22

What is interesting about this chart is the instability from year to year in unrestricted net assets, some years rising and others falling . When unrestricted net assets fall into negative percentage changes, it usually means the college is reporting deficits for the year. For private colleges with small endowments, serial deficits could threaten the financial survival of the college.

Chart 3 indicates that the full effect of federal pandemic funds did not appear until 2021, when each enrollment group in our study had an increase in unrestricted net assets Nonetheless, in 2022, the three enrollment groups experienced sharp declines in unrestricted net assets, and small colleges had the largest decline (-38.5%).

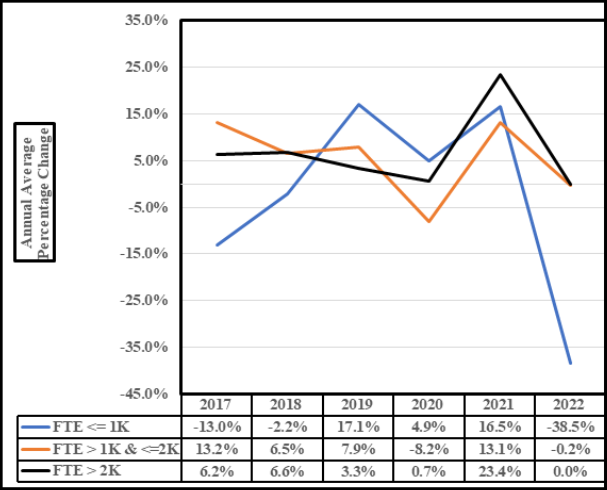

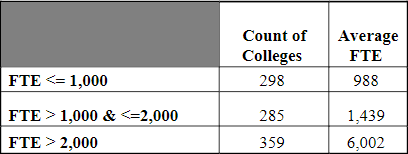

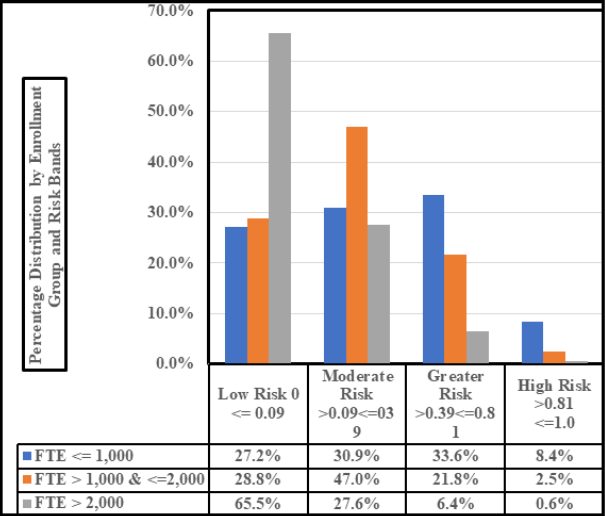

Chart 4 presents a different look at the distribution of colleges by enrollment group and risk bands. It confirms that risk follows scale of enrollment with small colleges facing the most risk of financial failure. According to IPEDS data, small colleges rated as greater to high risk have on average enrollment of 1,200 students.[10]

Chart 4

Distribution of Colleges in Research Set by Enrollment (FTE) Groups and Risk Bands

The relationship of size and vulnerability for private colleges and universities should not come as a surprise, because most private colleges are tuition dependent. Small tuition dependent colleges are especially vulnerable. There are several issues that make the economics and finances of small colleges problematic:

- Recall this quote from Ernest Hemingway’s masterpiece, The Sun Also Rises, “How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked. “Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.” Small colleges often lack the financial flexibility when price competition is intense (i.e., tuition discounts, as reported by NABUBO studies), leading to smaller and smaller yields from tuition enrollment.

- Breakeven price rises owing to accreditation, governmental requirements, and student expectations tend to increase fixed costs, which will increase breakeven prices due to the small number of students available to cover fixed costs. The chief financial officer and marketing office must then increase tuition discounts to remain competitive. Here is where the dilemma arises for the chief financial officers at tuition dependent colleges: Rising tuition discounts diminishes the flow of cash from tuition revenue. Less cash from tuition means that there may be insufficient cash to cover expenses. Under this predicament, these colleges lose twice – they have insufficient net revenue to cover expenses leading to a deficit, and cash reserves shrink because cash flow from revenue does not replenish reserves. As noted above, serial deficits can run the college into the ground.

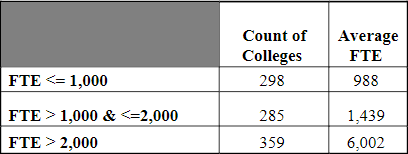

Table 2[13]

Number of Colleges and Average FTE for Each Enrollment Group

Conditions Unique to Higher Education that Degrade Response to Risk

Before any remedy can be prescribed, we need to understand why so many private colleges are slow to respond to economic and financial threats to their existence. The list at the start of this paper identified several factors that shape financial stress, but there are further internal and operational issues that also shape the financial vulnerability at small private colleges. See the following list of issues that may foster financial stress.

- Contradictions of dual governance, where major academic financial problems, and their solutions may be stymied by conflict between the manner in which faculty and administrative govern their respective areas.

- Faculty tenure that places costs, sometimes substantial, for the dismissal of faculty due to a major reorganization and the termination of academic majors or programs.

- Explicit and implied contracts with students, faculty, and external partiesin student handbooks that sets out the liability to students when programs, athletic programs student services, or dormitories are ended or downsized, faculty handbooks that specifiy work conditions, alumni traditions that carry costs, or unstated relationships with local governments that have inherent costs.

- Accreditation and governmental regulations that may stipulate financial conditions to sustain operations and standards for academic programs and student services that can a) raise the cost of operations and b) make it difficult to change academic programs. Governmental regulations can also stipulate financial conditions and standards for maintaining eligibility for federal funds or for compliance with federal mandates.

- State Non-Compete Regulations can keep a college from offering a new program if another institution already offers it.

- Human Capital, buildings and equipment may not match what a college needs during a strategic reorganization to better serve its student market while reducing costs.

Besides the preceding organizational failures, leadership failures by the president and board of trustees shape a private college’s capacity to rapidly respond to financial crisis and building financial vulnerability –. For the last ten years, top leadership at fiscally and operationally stressed private colleges have unintentionally exacerbated problems until a college collapses and closes. Salient characteristics of the leadership failures include:

Presidents

- Risk aversion, when dealing with fundamental changes in student and job markets;

- Tendency to substitute platitudes for real hard-nosed planning

- Not understanding that there are no new student markets, as there were in the eighties and nineties, when women and minorities enrolled in ever-larger numbers;

- Not recognizing that time is short for action and resources are quickly being depleted by every passing day.

Boards of Trustees

- Trustees may not invest either the time or energy to understand the perilous condition of their institution.

- Trustees, in some instances, may not have policy-making or management experience.

- Trustees may be unwilling to challenge claims made by the administration that all is well despite contradictory and obvious evidence.

- Trustees too often do not take the financial problems of the institution seriously until they like the president discover that the college has too few resources and very little time left.

- The Board may not fully appreciate its culpability for failing to oversee and preserve the resources of the institutions for future generations of students.

Potential Remedies for Reducing Financial Risk

Responding to the highest level of financial risk first requires information that delineates the financial, operational, and market conditions of the institution. Before diving into strategic and operational turnaround strategy, the president and board need to acknowledge whether or not operational deficits have become a recurring and increasing threat. In the next step, both the board and president need to know the level of financial reserves currently available, whether those reserves are expanding or shrinking, and how long those reserves will last, if there are operational deficits.

After the board and president fully agree that the college is at risk of financial failure, the board should arrange for a third party to evaluate the college’s – financial condition, in particular, cash flow; academic program contribution to financial performance; the connection between labor markets and academic programs; and the expectation of the student market. There is no surer sign of performance inefficiency than a major with three or more full-time faculty instructing four students in a major.

It is imperative for recognize that Boards need to support Presidents who lead with fortitude, intelligence, and foresight, otherwise it will be difficult for the institution to withstand conflict generated by internal and external dissension in response to major strategic changes. Conflicting solutions and dissension could become a regular event. Nonetheless, every day lost, before taking steps to overcome the inertia toward failure, will push the college closer to its demise.

Since time is of the essence, the board and its president must press-on with dispatch the president, faculty, staff, and administration moving forward while not letting precious time be excessively expended on internal politics and lack of follow-through. Of paramount importance in a survival turnaround is never losing a marketing season for new students. If that happens, the college could lose a year out of the precious short-time available to avoid financial failure.

The factors that make-up the Vulnerability Gauge can guide the development of an effective strategy to generate larger and positive net incomes that increase unrestricted net assets. Focusing on factors in the Vulnerability Gauge will lead to optimizing markets, generating higher cash flows from tuition, cutting administrative expenses, improving the financial and operational relationship between faculty and students, imposing controls on the operational efficiency of capital investments in grounds, buildings and equipment, and moving revenue generating centers toward positive contributions to the bottom line.

For colleges that have arrived at the brink of survival, there seem to be three strategic options that colleges at the brink of extinction consider:

- Merger

- Forming a partnership;

- Looking for wealthy alumni or local donors.

Usually, none of these three strategies are successful. The main reason is that colleges in dire straits have nothing to offer but debt, large financial liabilities, tenured faculty, unusable assets, law suits, and unhappy students and alumni. For the college being petitioned to help failing college, the best option may be to let it fail and pick up the pieces at a discount. The sad aspect of the current spate of college closings is that the causes for a particular institution may be beyond the control of its leaders. Over the next decade, private colleges and universities may operate in a different form and serve student markets with different characteristics, expectations, and capabilities.

Summary of the Main Points about the Vulnerability Gauge

The Vulnerability Gauge was developed as a tool for presidents, boards of trustees, and other interested parties to estimate the risk of financial failure for a private college.

- As noted above, colleges with enrollments of 2,000 or fewer students operate at a greater to highest level of risk. As is evident from news reports over the past several years, this group is shedding the most colleges. Small colleges have difficulty sustaining operations in a high-risk environment.

- The main issues threatening the survival of small, high-risk private colleges are: a shrinking pool of new students, the inflationary costs of operations, ever more stringent governmental regulations, and the loss of confidence by a growing number of high school graduates that a college degree may not be worth the cost.

- The Vulnerability Guage predicts the level of risk that a private college faces. It estimates financial risk using FTE enrollment and the change in unrestricted net assets. It also offers strategic entry points through the factors that are part of Guage.

- For the 201 small colleges living on the brink of survival, there is no timeto dawdle, action must be taken swiftly.

Reference

-

Higher Ed Dive Team ( March 11, 2024), “How many colleges and universities have closed since 2016”; Higher Ed Dive; How many colleges and universities have closed since 2016? | Higher Ed Dive. ↑

-

Moody, Josh (April 25, 2023); “Tuition Discount Rates Reach New High”; Inside Higher Education; NACUBO study finds tuition discount rates at all-time high (insidehighered.com). ↑

-

Some Colleges that Offer the Biggest Discount Rate; NICHE; (Retrieved March 26, 2023); Colleges That Offer the Biggest Discount – Niche Blog. ↑

-

Downes, Lindsey, editor (July 28, 2023) (Retrieved March 27, 2024); “How US Colleges Are Responding to Declining Enrollment”; WCET Frontiers; How U.S. Colleges and Universities are Responding to Declining Enrollments – WCET (wiche.edu). ↑

-

Student achievement gaps and the pandemic (Retrieved March 27, 2024); (Retrieved March 27, 2022); CRPE Reinventing Public Education; ED622905.pdf. ↑

-

Kuhfield, Megan, Jim Soland, Karyn Lewis, and Emily Morton (March 3, 2022) (Retrieved March 25, 2024): The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning”; Brookings; The pandemic has had devastating impacts on learning. What will it take to help students catch up? | Brookings. ↑

-

Mervosh, Sarah and Ashley Wu (October 24, 2022) (Retrieved March 27, 2024); “Math Scores Fell in Nearly Every State and Reading Dipped on National Exam”; New York Times; Math Scores Fell in Nearly Every State, and Reading Dipped on National Exam – The New York Times (nytimes.com). ↑

-

Heubeck, Elizabeth (February 21, 2024); (Retrieved March 27, 2024); “High School Students Think that They are Ready for College, But They Aren’t”; Education Week; High School Students Think They Are Ready for College. But They Aren’t (edweek.org). ↑

-

IPEDS (Retrieved March 1, 2024); Complete Data Files; IPEDS Data Center. ↑

-

IPEDS (Retrieved March 1, 2024); Complete Data Files; IPEDS Data Center ↑

by Michael K. Townsley | Jun 17, 2023 | Economics and Higher Education

First Published on Stevens Strategy Blog

Michael K. Townsley, Ph.D., Senior Associate Stevens Strategy

Prefatory Remarks

Notices of private colleges closing or merging have become regular items in the press. However, this sudden spate of bad news may not be entirely due to new problems or to the effects of COVID. Rather, long-term financial issues may have been masked by massive doses of Covid aid; and now that COVID aid (i.e., HEERF Funding) has ended, the long-term problems have resurfaced.

The most vulnerable colleges in the current economic environment are private non-profit colleges with a tuition-dependency rate greater than 80% (a 60% tuition-dependency rate typically signifies that a college is mainly dependent on tuition for revenue. An 80% tuition-dependency rate suggests that a college has a very small endowment and donations represent a small portion of total revenue.). Before the pandemic. 22% of private non-profit colleges had a tuition-dependency rate greater than 80%, according to data from IPEDS (Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System).

The survival of private colleges and universities with high rates of tuition-dependency is subject to how well they manage the basic economic duality of supply and demand in relation to the market price for tuition. When an institution gets crossways with market forces like supply, demand, and price, it may not generate sufficient cash to cover its everyday expenses.

As Richard Garrett, Chief Research Officer at Eduventures, recently said,

“The problem is that all these [basic economic] trends (demographics, lost revenue, higher costs) aren’t going to get any better anytime soon. [For instance], the demographics are only going to get worse over the long-term.”

Basic Economics

Demand

For tuition-dependent private colleges, the key threat is the falling birth rates since the year 2000. Falling birth rates have led to a smaller pool of prospective student pools, and the pool is projected to continue to contract for the remainder of this decade. A shrinking prospective-student pool means tougher price completion and greater threats to tuition-dependent colleges.

Table I

Degree Seeking Students at 4-year Private Non-profit Institutions

|

|

Total (thousands)

|

Change

|

% Change

|

|

2017

|

2,554

|

|

|

|

2018

|

2,548

|

-6.0

|

-0.2%

|

|

2019

|

2,524

|

-24.0

|

-0.9%

|

|

2020

|

2,494

|

-30.0

|

-1.2%

|

|

2021

|

2,465

|

-29.0

|

-1.2%

|

|

2022

|

2,448

|

-17.0

|

-0.7%

|

|

Total Change

|

-106.0

|

-4.2%

|

| |

|

|

Table I from the National Student Clearinghouse shows that enrollments steadily declined for undergraduate degree-seeking students between 2017 and 2022. From 2017 to 2022, 106,000 fewer students enrolled resulting in a loss of a sizeable amount of revenue and cash from tuition.

National Student Clearinghouse data (SEE Table II) also shows that no region of the country was spared from declining enrollments. Post-COVID in 2021, enrollment declines continued except for the West where enrollments increased. The pace of the fall in enrollments improved in 2022 except for the South, which reported a small increase, and the West, where enrollments abruptly decreased by its highest level in the past five years. Projected enrollment trends suggest improving conditions for enrollment; but based upon market factors (such as cost, perceived need for a college degree, and demographic shifts), it appears that enrollment increases will only be temporary before returning to a pattern of fewer students.

Table II

Changes in Total Enrollment (000) for Private Institutions 2017 to 2022

|

|

2018

|

2019

|

2020

|

2021

|

2022

|

Total

|

|

Midwest

|

(147)

|

(60)

|

(182)

|

(81)

|

(38)

|

(508)

|

|

Northeast

|

(82)

|

(53)

|

(122)

|

(92)

|

(16)

|

(365)

|

|

South

|

(99)

|

(19)

|

(131)

|

(144)

|

10

|

(383)

|

|

West

|

(93)

|

(17)

|

(152)

|

478

|

(624)

|

(408)

|

|

Nation

|

(421)

|

(149)

|

(587)

|

161

|

(668)

|

(1,664)

|

For tuition-dependent colleges, demand has been weakened by a nearly twenty-year- long drought in new births; and supply has been upset by students no longer selecting traditional liberal arts majors.

Ten years ago, evidence began to accumulate that college graduates were choosing careers that were not related to their majors. The Wall Street Journal reported “that colleges are separating into winners and losers because students are rejecting colleges which consistently ranked low in preparing students for work.” The majors with the highest levels of underemployment is when the average wage for a graduate is less than the average wage for all college graduates). The underemployed majors were: psychology, visual and performing arts, and the social sciences. The federal government is well aware of this deficit and is likely to mandate that all schools provide to prospective students a program-level report of employability for their graduates, likely in an effort to reduce student loan debt moving forward.

Net Price

Usually, the relative balance of demand and supply among competitors determines price. The current state of demand in higher education has unbalanced the demand and supply relationship, especially for tuition-dependent institutions that have seemingly lost control of pricing. Therefore, we will discuss price or tuition before we consider the supply part of the basic economic duality.

Price in higher education, in particular among tuition-dependent colleges and universities, consists of two components – posted tuition and net price. The posted tuition is the amount that institutions typically present as the full-cost for enrollment. Net Price, on the other hand, is the amount paid by the student after deducting unfunded institutional and other financial aid (loans are not a form of financial aid because they must be repaid). Net price is the amount of tuition remaining after unfunded institutional aid (tuition discount) is deducted.

Unfortunately for tuition-dependent colleges, as the prospective student market erodes, there is ever-greater pressure by competitors to increase tuition discounts leading to ever-smaller levels of net tuition (See Chart I). Today, some colleges are already offering tuition discounts of 70% or more of the posted tuition. High tuition discount rates barely leave enough cash to make payroll and cover their outstanding bills.

Chart I

NACUBO Chart on Tuition Discounts

As Kenneth Redd, Director of Research and Policy Analysis at NACUBO, has stated,

“There are two reasons for the [current and future] escalation [in tuition discounting.] ‘One is that the competition for students now has become extremely fierce,’ he says. ‘[And with] birthrates steadily falling, fewer young people are applying to college. The second reason: more families are financially strapped.’

Supply

Supply is the product or service offered by an organization to prospective buyers. For tuition-dependent private colleges, the product typically is an academic degree. The decision for the board of trustees and president is how much supply to offer and the net price (net tuition) to offer students in the marketplace.

It is all too obvious that larger tuition (price) discounts are not yielding larger enrollments. Tuition discounting has become a losing strategy. As William Hall, President of Applied Policy Research, has noted,

“If you want to grow [and survive], you’re going to have to do something [distinctive] to induce additional yield.”

A survey in 2019 indicated that 27% of college graduates regretted choosing a humanities major (i.e., liberal arts major). By 2022 the percentage of graduates with regrets about choosing a humanities degree had increased to 48%. Buyer’s remorse of nearly 50% can have a spillover effect to prospective students, who are also looking for majors more directly connected to future employment. When graduates in the liberal arts disciplines express this level of dissatisfaction, it will further depress the market for liberal arts programs. Dissatisfaction among current students is also evidenced by attrition. Attritted students are not returning to college as they once did, regardless of the blandishments offered (Examples of blandishments include: large discounts, on-line courses, counseling, payment alternatives, loan restructuring, and other offers that admission and marketing officers have devised.)

Of considerable concern to private colleges chiefly offering liberal arts or humanities degrees is that high school graduates are moving away from those majors and seeking more practical job-oriented degrees or even opting for certificates or other non-degree options to improve their value in the work force. None of these bode well for the future of private liberal arts colleges.

With fewer prospective students choosing liberal arts or humanities majors, tuition-driven liberal arts college are bearing the burden of over-investment in fixed capital assets (buildings and furnishings) and faculty assigned and tenured in these programs. Moreover, the liberal arts faculty, especially tenured faculty, are not easily moved into new programs such as offering degrees in business or technology. Additionally, when students do not attain a liberal arts degree, it causes a second-level problem. In the past, 40% of liberal arts graduates went on for an advanced degree (e.g., philosophy bachelor’s degree graduates would earn a master’s in philosophy), which generated more tuition revenue.

Transforming a liberal arts college into a more career-oriented institution can have profound challenges because the institution is overly invested in degrees that prospective students no longer want. However, an article from Inside Higher Education in 2012 pointed out that some liberal arts colleges, though keeping liberal arts in their mission, were moving their curriculum toward more practical workplace applications.

One of the primary strategies for a supplier operating in an intensely price-competitive marketplace, is to differentiate themselves from their competitors. Colleges and universities have introduced multiple strategies over the years to differentiate themselves from their competitors. Here are several examples of differentiation strategies used by tuition-dependent colleges: block scheduling, new academic programs, schedules that accommodated working students, easing transfer credit rules, opening off-site instructional programs, contracting special discounts to groups of students (e.g., a cohort of law enforcement officers), online programs, and offering college credit courses to high school students. The most recent and almost universally example of colleges responding to changes in the marketplace is when the pandemic forced colleges without online courses to quickly install the online technology or lose their students. What will tuition-dependent colleges do in the future to expand revenue flows? That will depend on how quickly a president can see new opportunities, which are dependent on location, flexibility of the institution, and access to financial resources.

Besides the differentiation of products and services, there is one other significant option — cut the cost of producing the product. Cutting cost reduces upward pressure on pricing. Most colleges find this option the most difficult to implement because of internal (faculty, students, athletic programs, etc.) and external (alumni, government regulations, donors, etc.) constraints. Yet, college presidents and boards of trustees must understand that when costs per student rise faster than the income from prospective student, they will never get control of an institutional pricing strategy or of its long-term financial viability.

The Chronos Option

For tuition-dependent institutions looking to respond effectively to the demands of the market, Stevens Strategy has developed Chronos UniversityTM., a revolutionary design for the university of the future. It meets the needs of tuition-dependent institutions: It lower their costs of operation by maximizing faculty effectiveness, responds to the expectations of the new generation of students by creating opportunities for a consistent, personalized experience, applies technology to enhance instruction, and places the university in a distinctive position in its market by taking a unique, student-focused approach to higher education.

The Chronos concept integrates technology-based instruction with on-site or remote small group projects and daily face-to-face interaction with learning coaches to promote student learning and success. Chronos UniversityTM is designed to revolutionize the delivery of high-quality liberal arts and pre-professional undergraduate education. Interested readers can learn more about Chronos here.

Summary

Tuition-dependent colleges need to be keenly aware of their competitors and the goals and abilities of their prospective students. In the past, private colleges could offer a new way of differentiating themselves from the competitive herd, and it would take several years for the competition to react and to offer the same thing. During this period, a college could design new products or services and generate positive cash flow that strengthened its financial base. In today’s higher education marketplace, competitors will quickly react when another institution offers a program that enrolls a large number of new students spawning more revenue. Competitors will quickly replicate those programs because they are also desperate for new revenue sources.

When an institution is out-of-balance with market forces, it must act promptly to rebalance its relationship with the market. The college will need to speedily innovate or lose its capacity to survive. Presidents and boards of trustees of tuition-dependent colleges need to recognize that survival and success in their market depends on the interaction of demand and supply on the price of tuition, on their competitors and their goals and plans, on the income of prospective students and their capacity to pay the tuition bill, and on the students and/or families to see a payoff from tuition debt.

As is evident to anyone working or knowledgeable of higher education, declining enrollments combined with the other fundamentals (such as student preferences for an academic degree, net price, inflation, and unexpected expenses or situations like COVID) are pushing many private colleges to the precipice of failure.

As noted at the very start of this article, economic conditions are forcing some non-profit private colleges to merge or to close. (This is what happens in the business sector when a sector of the business market can no longer sustain revenues to cover expenses. For example, online catalogue stores and monster big box stores destabilized traditional retail operations.) Presidents can be continually on the lookout for strategic partnerships, like articulation agreements, or merger opportunities since one might emerge that makes sense. Merger partners should be considered before the school spirals too far down and has no value to a potential partner. Finally, trustees may determine that they do not want to modify the institutional mission to meet the market or that the institution has no long-term financial viability and decide that closing the school is the best option. A school closing should be considered early so students, employees and vendors are not left in a lurch.

Boards and presidents need to seriously evaluate a school’s financial position and review strategies — realistic increased revenue opportunities, expense reductions, merger partners, and closing plans. A fiscally-prudent board of trustees at a tuition-dependent private college must get a grip on the condition of the institution that they are charged with overseeing. Otherwise, the future of the college and its responsibilities to its students may slip out of their hands.

PUBLICATION NOTES

N.B.; these notes are from the original paper. The original location of the endnote numbers in the body of the paper were removed due to issues with publication on the Blog Site. If you desire an original copy of the paper; contact mtown@dca.net

Moore, Keller (September 8, 2022); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Did you know? College closures are on the rise”; The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal; Did You Know? College Closures Are On the Rise — The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal (jamesgmartin.center).

Integrated Postsecondary Education Data Systems (Retrieved April 2023); “Robust SS Stress Test”; The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System.

Burns, Hilary (April 28, 2023); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Why the business of small colleges no longer adds up”; Boston Globe; Why the business of small colleges no longer adds up (msn.com).

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (February 2, 2023); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Table 1: Enrollment by Credential Level and Sector 2017-2022”; Current Term Enrollment Estimates | National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (nscresearchcenter.org).

Ibid; Current Term Enrollment Estimates | National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (nscresearchcenter.org).

Grawe, Nathan (January 4, 2020); “Demographics, demands, and destiny: Implications for the health of independent institutions”; 2020 Annual Meeting of the Council of Independent Colleges; slide 14.

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (February 2, 2023); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Table 2: Total Region Enrollment 2017-2022”; Current Term Enrollment Estimates | National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (nscresearchcenter.org).

Schwartz, Natalie (May 23, 2023); (Retrieved May 23, 2023); “Bain warns of ‘perilous environment’ for colleges as COVID 19 relief dries up”; Bain warns of ‘perilous environment’ for colleges as COVID-19 relief dries up | Higher Ed Dive.

Hill, Cary (June 27, 2019); (Retrieved May 24, 2023); “This the most regrettable college major in America”; Market Watch; This is the most regrettable college major in America – MarketWatch. Plumer, Brad (May 20, 2013); (Retrieved May 15, 2023); “Only 27% of college graduates have a job related to their major; The Washington Post; https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/05/20/only-27-percent-of-college-grads-have-a-job-related-to-their-major/?utm_term=.bb8684d901e4. Belkin, Douglas (February 21, 2018); (Retrieved April 28, 2023); “U.S. colleges are separating into winners and losers”; The Wall Street Journal.

Cooper, Preston (June 8, 2018); Retrieved May 15, 2023); Underemployment persists throughout college graduates’ careers”; Forbes; https://www.forbes.com/sites/prestoncooper2/2018/06/08/underemployment-persists-throughout-college-graduates-careers/#547d9a087490.

Adams, Susan (May 20, 2021); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Colleges are discounting tuition more than ever”; Forbes; Private Colleges Are Discounting Tuition More Than Ever (forbes.com).

Ibid; Forbes; Private Colleges Are Discounting Tuition More Than Ever (forbes.com).

Moody, Josh (April 25, 2023); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Tuition discount rates hit new high”; Inside Higher Education; NACUBO study finds tuition discount rates at all-time high (insidehighered.com).

Hill, Cary (June 27, 2019); (Retrieved May 24, 2023); “This the most regrettable college major in America”; Market Watch; This is the most regrettable college major in America – MarketWatch.

Drozdowski, Mark (September 29, 2022); (Retrieved May 24, 2023); “College grads regret majoring in humanities fields”; Best Colleges.com; College Grads Regret Majoring in Humanities Fields | Best Colleges.

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (April 25, 2023); (Retrieved May 14, 2023); “Some college, no credential”; Some College, No Credential | National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (nscresearchcenter.org).

Ezarik, Melissa (March 20, 2022); (Retrieved May 14, 2023); “Students approach admissions strategically and practically”; National Student Clearinghouse Research Center; Survey: Student college choices both practical and strategic (insidehighered.com).

Barshay, Jill (November 22, 2021); (Retrieved May 14, 2023); “The number of college graduates drop for the eight straight year”; Hechinger Report; The number of college graduates in the humanities drops for the eighth consecutive year | American Academy of Arts and Sciences (amacad.org).

Ibid; Hechinger Report; The number of college graduates in the humanities drops for the eighth consecutive year | American Academy of Arts and Sciences (amacad.org).

Jaschik, Scott (October 10, 2012); (Retrieved May 24, 2023); “Disappearing liberal arts colleges; Inside Higher Education; Study finds that liberal arts colleges are disappearing (insidehighered.com).

Moore, Keller (September 8, 2022); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Did you know? College closures are on the rise”; The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal; Did You Know? College Closures Are on the Rise — The James G. Martin Center for Academic Renewal (James martin. center).

Integrated Postsecondary Education Data Systems (Retrieved April 2023); “Robust SS Stress Test”; The Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System.

Burns, Hilary (April 28, 2023); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Why the business of small colleges no longer adds up”; Boston Globe; Why the business of small colleges no longer adds up (msn.com).

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (February 2, 2023); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Table 1: Enrollment by Credential Level and Sector 2017-2022”; Current Term Enrollment Estimates | National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (nscresearchcenter.org).

Ibid; Current Term Enrollment Estimates | National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (nscresearchcenter.org).

Grawe, Nathan (January 4, 2020); “Demographics, demands, and destiny: Implications for the health of independent institutions”; 2020 Annual Meeting of the Council of Independent Colleges; slide 14.

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (February 2, 2023); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Table 2: Total Region Enrollment 2017-2022”; Current Term Enrollment Estimates | National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (nscresearchcenter.org).

Schwartz, Natalie (May 23, 2023); (Retrieved May 23, 2023); “Bain warns of ‘perilous environment’ for colleges as COVID 19 relief dries up”; Bain warns of ‘perilous environment’ for colleges as COVID-19 relief dries up | Higher Ed Dive.

Hill, Cary (June 27, 2019); (Retrieved May 24, 2023); “This the most regrettable college major in America”; Market Watch; This is the most regrettable college major in America – MarketWatch.

Plumer, Brad (May 20, 2013); (Retrieved May 15, 2023); “Only 27% of college graduates have a job related to their major; The Washington Post; https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2013/05/20/only-27-percent-of-college-grads-have-a-job-related-to-their-major/?utm_term=.bb8684d901e4.

Belkin, Douglas (February 21, 2018); (Retrieved April 28, 2023); “U.S. colleges are separating into winners and losers”; The Wall Street Journal.

Cooper, Preston (June 8, 2018); Retrieved May 15, 2023); Underemployment persists throughout college graduates’ careers”; Forbes; https://www.forbes.com/sites/prestoncooper2/2018/06/08/underemployment-persists-throughout-college-graduates-careers/#547d9a087490.

Adams, Susan (May 20, 2021); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Colleges are discounting tuition more than ever”; Forbes; Private Colleges Are Discounting Tuition More Than Ever (forbes.com).

Ibid; Forbes; Private Colleges Are Discounting Tuition More Than Ever (forbes.com).

Moody, Josh (April 25, 2023); (Retrieved May 12, 2023); “Tuition discount rates hit new high”; Inside Higher Education; NACUBO study finds tuition discount rates at all-time high (insidehighered.com).

Hill, Cary (June 27, 2019); (Retrieved May 24, 2023); “This the most regrettable college major in America”; Market Watch; This is the most regrettable college major in America – MarketWatch.

Drozdowski, Mark (September 29, 2022); (Retrieved May 24, 2023); “College grads regret majoring in humanities fields”; Best Colleges.com; College Grads Regret Majoring in Humanities Fields | Best Colleges.

National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (April 25, 2023); (Retrieved May 14, 2023); “Some college, no credential”; Some College, No Credential | National Student Clearinghouse Research Center (nscresearchcenter.org).

Ezarik, Melissa (March 20, 2022); (Retrieved May 14, 2023); “Students approach admissions strategically and practically”; National Student Clearinghouse Research Center; Survey: Student college choices both practical and strategic (insidehighered.com).

Barshay, Jill (November 22, 2021); (Retrieved May 14, 2023); “The number of college graduates drop for the eight straight year”; Hechinger Report; The number of college graduates in the humanities drops for the eighth consecutive year | American Academy of Arts and Sciences (amacad.org).

Ibid; Hechinger Report; The number of college graduates in the humanities drops for the eighth consecutive year | American Academy of Arts and Sciences (amacad.org).

Jaschik, Scott (October 10, 2012); (Retrieved May 24, 2023); “Disappearing liberal arts colleges; Inside Higher Education; Study finds that liberal arts colleges are disappearing (insidehighered.com).